Books |

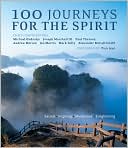

100 Journeys for the Spirit

By

Published: Jun 04, 2020

Category:

Spirituality

Reading “100 Journeys for the Spirit ” a brisk (225 pages) photograph-driven guide with short essays by Pico Iyer, Michael Ondaatje, Paul Theroux and a few other writers, I was forced to admit that there were many stops on this guided tour of the planet’s most spirit-drenched destinations that I’d never even heard of. Or that I kinda sorta knew about, but couldn’t answer a multiple-choice question on the Geography of Spirit final exam.

I knew — of course I knew — Bryce Canyon in Utah. The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming. The Nazca Lines, the Serpent Mound in Ohio. Most of the religious sites (and the book covers the full range). I knew — but had forgotten — the island off Venice called Torcello.

Alas, my knowledge went only so far.

I knew nothing of the lakeside villages of Guatemala’s Lake Atitlan, the ruins at Tiwanaku in Bolivia, the Great Blue Hole in a reef in Belize, the quarry-like rock face of Pipestone in Minnesota, the Godafoss Waterfall in Iceland, The Ring of Brodgar in Scotland, Carnac in France, the gorgeous simplicity of the St.-Peter-on-the Wall Church in England. the Talati de Dalt stone remnants on Menorca, Morvern in Scotland, the instantly classic Sogn Benedetg chaptel in Switzerland — and that’s just my list from the first half of the book. By the time the book reached gorgeous, unspoiled, spooky Australia and New Zealand. [To buy the book from Amazon, used but in good condition, at a giveaway price, click here.]

But this, it turns out, is not the point.

First is the issue of the traveler him/herself. Here’s Pico Iyer:

We all know how we can be turned around by a magic place; that’s why we travel, often. And yet we all know, too, that the change cannot be guaranteed. Travel is a fool’s paradise, Emerson reminded us, if we think that we can find anything far off that we could not find at home. The person who steps out into the silent emptiness of Easter Island is, alas, too often the same person who got onto the plane the day before at Heathrow, red-faced and in a rage.

Yet still the hope persists and sends us out onto the road: certain places can so shock or humble us that they take us to places inside ourselves, of terror or wonder or the confounding mixture of them both, that we never see amidst the hourly distractions and clutter of home. They slap us awake, and into a recognition of who we might be in our deepest moments.

I will never forget walking out onto the terrace of my broken guest-house in Lhasa, in 1985, and seeing the Potala Palace above what was then just a cluster of traditional whitewashed Tibetan houses, its thousand windows seeming to watch over us. I will never forget, too, visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem two years ago and feeling, whether I wanted to or not, all the prayers, hopes and complications that people had brought to it. The place is as dark, irregular and everyday as the fights it houses — as worldly and human as the Potala seems the opposite — and yet the very fact that so many millions have come for centuries to pray and sob among its flickering candles ensures that many more will do so, even if, like me, they’re not Christian or Buddhist.

But even more significant is the interior destination. Iyer, again:

At the end of the last century, an editor at an online magazine asked me to write an essay on a "Sacred Space". He was expecting a piece on Machu Picchu or Stonehenge, I knew, but I wrote about my little blond-wood desk. He asked for a second essay, and I wrote on memory, everything inside me. Yet if I hadn’t been to Greece and Burma, if I hadn’t stood, wordless, before Ayers Rock and Notre-Dame, I’m not sure that I’d have been able to see how much was available to me at my desk or just by closing my eyes and looking back. A journey of the spirit only starts with somewhere wondrous. It continues wherever we are, through the doors that wonder has opened.

“100 Journeys” is a dreamscape. Dream on.