Books |

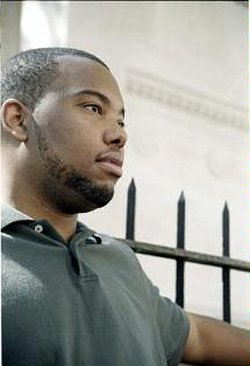

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Between the World and Me

By

Published: Jul 14, 2015

Category:

Memoir

It’s a spectacular irony that Go Set a Watchman and “Between the World and Me” were published on the same day. One upends half a century of admiration for Atticus Finch by suggesting that Southern whites who seemed heroic in the early years of the Civil Rights struggle were tainted by racism. The other makes the case that America is built on racial suppression, that slavery and plunder define the country — that American blacks are, in essence, born in jail. One book is fiction, a footnote to literature. The other is perhaps the most important book of the year. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

“Between the World and Me” was to be published in October. Then Charleston happened. And Baltimore. And Charleston again. Toni Morrison embraced the book: “I’ve been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin died. Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates.” And now, months early and right on time, here it is.

Coates was then a National Correspondent for the Atlantic.com. In 2014, he wrote a widely read 15,000-word cover story for The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations.” In that piece, he argued that black Americans are, essentially, owed a fortune for the abuses of a system that was built on their labor and discriminates against them to this day.

His book is a 155-page letter to his teenaged son. “Here is what I would like for you to know,” he writes. “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body — it is heritage.”

If he’s obsessed with the body — especially the bodies of black men — it’s not only because he’s been reading history ever since he went to Howard University, but because the vulnerability of his own body is the first life lesson he learned as a kid growing up in Baltimore. Racism may be policy, he argues, but it always seems to be expressed as violence. As he writes to his son:

Racism is a visceral experience, It dislodges brains. It dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth, extracts testicles.

Rhetoric? A page later, he writes about his son’s reaction to the news that the policeman who shot Michael Brown wouldn’t be indicted:

You said, ‘I’ve got to go,’ and you went into your room, and I heard you crying. I came in five minutes after, and I didn’t hug you, and I didn’t comfort you… I didn’t tell you it would be okay, because I never believed it would be okay.

So the first part of the book is about “plunder,” the systematic theft of safety and good schools and affordable homes and safe streets.

The second part covers his years at Howard University. The library was major (“I was made for the library, not the classroom”), he wrote poems, he met his wife. Howard was “Mecca.” It’s always sweet to read about self-discovery, even what what’s learned is painful.

The third section is the most straightforward and heartbreaking. It’s not theoretical, it doesn’t advance an argument, it just tells a story about a Howard student named Prince Carmen Jones. He was aptly named: “lean, brown and beautiful.” And then, in a case of mistaken identity, a Virginia cop — a black cop — shot and killed him. Was the cop prosecuted? What do you think?

Years later, Coates visits his friend’s mother. If you have tears, prepare to shed them.

It’s a sad truth that if a million people die, it’s a statistic. But if a dog is run over in the street, we mourn. So it’s one thing when Coates writes that blacks in America find themselves in “unbreakable chains.” It’s quite about to walk around, as you will, with Prince Jones in your head.

In the end, though, this isn’t a book only about race. It’s much more about plunder.

The plunder of black life was drilled into this country in its infancy and reinforced across its history, so that plunder has become an heirloom, an intelligence, a sentience, a default setting to which, likely to the end of our days, we must invariably return.

At the end of the book, Coates widens the lens, because plunder isn’t, he says, limited to what America does to blacks. It’s bigger. It’s our DNA. It’s everywhere.

Please read this book.