Books |

And There Was Light: The Autobiography of Jacques Lusseyran, Blind Hero of the French Resistance

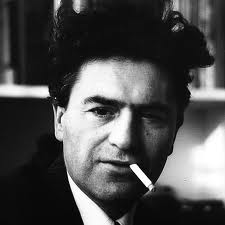

Jacques Lusseyran

By

Published: Aug 22, 2022

Category:

Memoir

His favorite color was green — the color, he later learned, of hope.

And hope is what pours over you on every page of Jacques Lusseyran’s memoir. It’s unavoidable. It’s the DNA of the book.

For Jacques, early childhood was heaven. He ran. He played. God was “just there.” As he says, “Behind my parents there was someone, and my father and mother were simply the people responsible for passing along the gift.”

At 7, he had an accident in school. The shaft of his glasses stabbed his right eye and tore away the tissue. The left eye had sympathetic damage. The happy-go-lucky Paris schoolboy woke up, his eyes bandaged.

He was totally blind.

And he was completely happy.

Despair, he realized, was simply a matter of “looking the wrong way.” In fact, he could see — “radiance [was] emanating from a place I saw nothing about.” He could see light, after all. It only faded when he was afraid.

The world was still beautiful — indeed, more beautiful. Waves were “arranged in steps.” Voices could be caresses. Metaphor was everywhere: “Before I was ten years old, I knew with absolute certainty that everything in the world was a sign of something else.” So blindness was an obstacle, but it was also like a drug — it made other senses intoxicatingly intense.

“They told me that to be blind meant not to see. Yet how was I to believe them when I saw? Not at once, I admit…for at that time I still wanted to use my eyes…and there was anguish, a lack, something like a void which filled me with what grown ups call despair…one day…I realized I was looking in the wrong way…it was a revelation…I began to look more closely, not at things, but at a world closer to myself, looking from an inner place to one further within, instead of clinging to the movement of sight toward the world outside. Immediately the substance of the universe drew together, redefined and people itself anew. I was aware of a radiance emanating from a place I knew nothing about, a place which might as well have been outside me as within. But radiance was there, or to put it more precisely, Light. I found light and joy at the same moment, and I can say without hesitation that from that time on light and joy have never been separated in my experience. I have had them or lost them together.”

High school. Academics. Friends. Girls. Happy days. His mother learned Braille. His father took him every week to the symphony.

“The world of violins and flutes, of horns and cellos…obeyed laws which were so beautiful and so clear that all music seemed to speak of God. My body was not listening, it was praying. My spirit no longer had bonds…I wept with gratitude every time the orchestra began to sing. A world of sounds for a blind man, what sudden grace! No more need to get one’s bearings. No more need to wait. The inner world made concrete. I loved Mozart so much, I loved Beethoven so much that in the end they made me what I am… Intelligence, courage, frankness, the conditions of happiness and love, all these were in Handel, in Schubert, fully stated, as readable as the sun high in the sky at noon.”

But we know what was coming: the Nazi occupation. Jacques was a patriot. At 17, he decided to organize his friends into a resistance unit. Wisely, they appointed him head of recruiting — his hearing made him a great judge of character. Later he and his friends started an underground newspaper; it would become France-Soir, the most important daily newspaper in Paris. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

His luck ran out in 1943, when a man who Jacques had grudgingly admitted to their group betrayed them all. After spending 180 days in a cell in France, he was transferred to Buchenwald. Two thousand other Frenchmen were sent with him. Fifteen months later, when the Nazis were defeated, only thirty of them were still alive.

“I was nothing but skin and bones, but I had recovered. The fact was I was so happy, that now Buchenwald seemed to me a place which if not welcome, was at least possible. If they didn’t give me any bread to eat, I would feed on hope… It was the truth. I still had 11 months ahead of me in the camp. But today I have not a single evil memory of those 333 days of extreme wretchedness. I was carried by a hand. I was covered by a wing. One doesn’t call such living emotions by their names. I hardly needed to look out for myself…I was free now to help the others; not always, not much, but in my own way I could help. I could try to show other people how to go about holding on to life. I could turn toward them the flow of light and joy which had grown so abundant in me.”

“Joy doesn’t not come from outside, for whatever happens to us, it is within,” he concludes. “Light does not come to us from without. Light is in us, even if we have no eyes.”

Goodness at this level makes commentary superfluous.