Music |

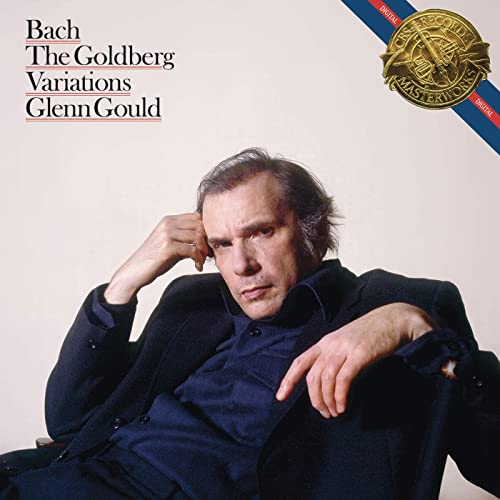

Glenn Gould: The Goldberg Variations

By

Published: Sep 23, 2020

Category:

Classical

Eric Motley, now executive vice president of the Aspen Institute, recalls how he met Ruth Bader Ginsberg:

Our improbable friendship began in 2002 at a Georgetown dinner party, and it began with music. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a Jewish urbanite who had just turned 69 and had been appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by a Democratic president. I was a 30-year-old African-American from the rural South who had recently arrived in Washington to serve as a special assistant to George W. Bush.

Aware of my status as the new kid on the block, I soon was put at ease at the dinner by the friendly man seated next to me, Marty Ginsburg. I’ll always remember our conversation.

So what do you do when you’re not working at the White House? he asked. I replied that listening to music and reading were my chief interests.

He turned and said, my wife and I love music; what are you listening to now?

When he learned that I was researching different renditions of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, he asked for my favorite. Without hesitation, I replied, “Glenn Gould, 1955.” Addressing his wife on the other side of the table, he said, “Ruth, you have to meet Eric.”

—–

In 1741, a Russian count who lived in Leipzig had trouble sleeping. To calm his nerves, Count Kaiserling ordered Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, his personal pianist, to play in the next room. And the Count asked Johann Sebastian Bach to provide Goldberg with some clavier pieces — music that would be soothing but cheerful.

Bach, at the height of his genius, was not about to knock off some insignificant ditties. Instead, he produced what’s been described as “the most serious and ambitious composition ever written for harpsichord.”

In form, the piece consists of an aria, thirty variations, and a repeat of the aria. The jaw-dropping achievement? Instead of writing variations on the melody, Bach built the piece by embellishing the ground bass line.

The Count loved Bach’s music. “Dear Goldberg,” he would say, “do play me one of my variations.”

Or so the story goes.

The Count claimed ownership — he had, after all, paid Bach with a golden goblet filled with a hundred gold pieces — but this work has never been known as the Kaiserling Variations.

For more than two hundred years, it was the Goldberg Variations.

And then, in 1955, the cognoscenti dubbed it the “Gouldberg” Variations.

Glenn Could was a certified prodigy. He could read music when he was just 3 years old and was composing at 5; now, at 22, he was about to make his debut for Columbia Records. His choice of music: The Goldberg Variations. And he’d play them not as written, but on a piano.

Gould’s recording sessions were instant legend. He had astonishing requirements: the right room temperature, the right chair. Before recording, he would soak his hands and arm to the elbows in hot water for twenty minutes. Eccentric? He hummed as he played. He rocked in his chair until it squeaked. But his interpretation was revolutionary: up-tempo, dramatic, technically dazzling.

No pianist has ever been hyped like Gould. Record of the year? Try the decade. But even that was too small. No sooner had Gould’s Goldberg Variations been released than critics were calling it one of the century’s greatest recordings. And the world agreed: Gould’s recording sold and sold and sold. [To buy the CD of the 1955 recording from Amazon for $10 and get a free MP3 download, click here. To buy the MP3 download for a ridiculous $1.29, click here.]

Gould’s astonishing debut — imagine if Bruce Springsteen had made "Born to Run" at, say, 15 — quickly cemented his legend as musician and eccentric. And then he topped himself. In 1981, the now 50-year-old pianist decided to re-record the Goldberg Variations in the same New York studio that was the setting for his 1955 debut.

Pressed for an explanation, Gould cited the advances in technology: stereo, Dolby. But more to the point, he said, he had listened again to his 1955 recording — and he’d found it “very nice, but 30 interesting, independent-minded pieces going their own way.” His self-assessment was harsh: His original recording contained "things that pass for expressive fervor in your average conservatory, I guess." [To buy the CD of the 1981 recording from Amazon for $10 and get a free MP3 download, click here.]

Some critics find Gould’s second recording superior: thoughtful, energetic, the interpretation of a mature artist. Others cite technical glitches and phrasing that couldn’t be explained as “eccentric”. Clearly, there’s no end to debate when the subject is Glenn Gould. But the overarching fact about this 1981 recording overwhelms the critical conversation — this was Gould’s last record. He died just a few weeks after it was released.

My opinion? I’m of the view that there’s no “wrong” choice here. Because to say one version or another of the Goldberg Variations is "better" is to miss the point. This is music — in any version — that belongs in every life.

For the Glenn Gould web site, click here.