Books |

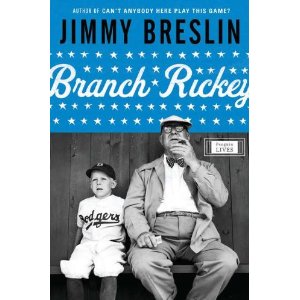

Branch Rickey

Jimmy Breslin

By

Published: Mar 27, 2023

Category:

Biography

Major League Baseball is racially integrated now: In 2022, 38% of the players were men of color. Before we tip our caps to a racially diverse sport, consider this: For the first time since Jackie Robinson’s early days as a big leaguer, there were no U.S.-born Black players in the 2022 World Series. Which brings me to Jimmy Breslin…I interviewed him the day after 9/11. “Security will make you weep,” he said. He was right. In another conversation, he said, “The poor can never be made to suffer enough.” Right again. In this short biography, he profiles Branch Rickey, the man who hired the man who, he contends, made Barack Obama possible. Right again? Possibly. This is certain: You don’t have to love baseball to love this book.

On the morning before John F. Kennedy’s funeral, every reporter in Washington crowded to be close to Kennedy’s coffin or along the route of the horse-drawn casket.

“I went to the White House in the morning,” Jimmy Breslin recalled. “I walked into the lobby and that was packed, and I said this is not for me. I saw Art Buchwald and we talked for a second and I said, ‘I can’t do any good here. I’m going to go over and get the guy who dug Kennedy’s grave.’ ‘Yeah, that’s a good idea,’ he told me, instantly. And I left there right away. I just turned and walked right out of the place and over to Arlington cemetery, and they got me the guy.”

Jimmy Breslin watched Clifton Pollard dig the president’s grave.

That column in the New York Herald Tribune — it’s a classic.

And it’s one of many. New York corruption schemes. The ‘Son of Sam” killer. Riots. Rudy Giuliani.

Of course he won a Pulitzer.

Jimmy Breslin didn’t have a low opinion of himself. “Media,” he likes to say, “is the plural of mediocrity.”

He had a point. Media kicks people only when they’re on the way down. Jimmy Breslin liked to kick them when they’re riding high. Cardinal Egan couldn’t bring himself to speak about pedophiles in the Church. “The man betrayed Catholics, and the Irish,” Breslin wrote, “and he puts on his red hat.” He savaged a then-popular governor: “’Society’ Carey, his mind like sky…”

Breslin wasn’t long-winded. His biography of Branch Rickey fills just 160 pages.

He didn’t want to write it — he was in his late 70s when Viking asked him to contribute to its series of brief biographies.

When they ask me to write a book about a Great American, right away I say yes. When I say yes, I always mean no. They ask me to choose a subject, and I say Branch Rickey. He placed the first black baseball player into the major leagues. His name was Jackie Robinson. He helped clear the sidewalks for Barack Obama to come into the White House. As it only happened once in the whole history of the country, I would say that is pretty good. Then some editors told me they never heard of Rickey. Which I took as an insult, a disdain for what I know, as if it is not important enough for them to bother with. So now I had to write the book.

And what a book! It is about baseball — but, really, it’s about so much more. And it’s the “much more” that makes this a sports book that should reach the widest possible audience. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For more ebooks by Jimmy Breslin, including one of his best journalism, click here.]

When Branch Rickey was a kid growing up in Ohio, Breslin writes, baseball was “for hillbillies with great eyesight.” Rickey played a bit of ball, but he was smart and hard-working, and he got himself an education. Armed with a law degree, he moved to Boise, Idaho, had one client, and decided it would be smarter to coach college baseball.

“He was neither a savior nor a Samaritan,” Breslin writes. “He was a baseball man, and nowhere in his religious training did he take a vow of poverty.” When he ran the St. Louis Cardinals, he started buying more teams. Soon he had invented the minor league farm system. And he invented a business — when he sold a player, he took ten percent commission.

In l943, in Brooklyn, he had a plan to make a great deal more money: ”There were a million blacks who played baseball. He knew right there … that it was only sensible to look for players who could make the Dodgers. And fill seats at Ebbets Field and all over the league.

Consider the year. Rickey started implementing his plan “four years before the armed forces were desegregated by Harry Truman, years before Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education, decades before the Civil Rights Act and Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Voting Right Act of 1965. On that day, Martin Luther King, Jr., was a junior in an Atlanta high school.”

No other owner supported Rickey. (Breslin: “The Red Sox owner, Tom Yawkey, would spend the next twenty years keeping blacks off his teams and he got what he deserved, which was nothing.”) No matter. He started looking for a player who was more than a great African-American athlete — he had to be willing to ignore racism on and off the field.

The account of Rickey’s conversations with Robinson is thrilling. So are the games. Media support? Non-existent: “No white editor in the North became a civil rights legend because no white in the North wanted anything to do with it.”

Breslin digresses, and these stories are priceless. How he needed cigarettes to write, and how he stopped smoking. New York politics: “The reason why people are in the best hands when they give their problems to a politician is that the man does favors for a living.” Why tobacco companies sponsored baseball.

And the sentences! “Until this morning, there has been no white person willing to take on the issue. That is fine with Rickey. He feels that he is up at bat with two outs and a 3-2 pitch coming. He is the last man up, sure he will get a hit.” Yes, you could teach a whole term in a writing class off just this short book.

On April 15, 1947, Jack Roosevelt Robinson stepped onto a major league field — and into history. And not just baseball history. When you read Breslin’s final chapter…. well, you’ll see.