Music |

Al Kooper: Blood, Sweat & Tears

Blood, Sweat & Tears

By

Published: Jun 25, 2014

Category:

Rock

You don’t have to be old to take this quiz. An acquaintance with Classic Rock will suffice.

Here’s the question: Which is your least favorite band of the 1970s — Chicago, Boston, or Blood, Sweat & Tears?

Easy to make the case against Boston. Just consider “More Than a Feeling.”

Even easier to hate is Chicago. Remember “Saturday in the Park?”

But them we come to Blood, Sweat & Tears, and all the bells ring. “Spinning Wheel.” “And When I Die.” And the ultimate bummer: “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy.”

Yes, Blood, Sweat & Tears gets my vote. The most annoying group of an entire decade. And for a reason I can’t use on the others.

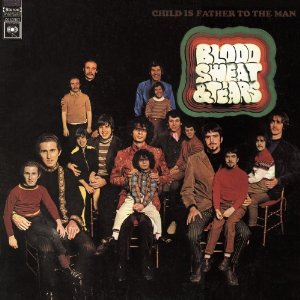

When Al Kooper led the group, Blood, Sweat & Tears made one of the most interesting, highest quality records of the 1960s: “The Child Is Father to the Man.”

When Al Kooper left… disaster.

Al Kooper? He may be unknown to you, but he’s a legend to musicians. As a kid, he was a session player on hundreds of teen hits. He gigged around, made a lot of friends, and one day in 1965, found himself in the studio watching Bob Dylan record. The project that day was “Like a Rolling Stone” — a song so extravagantly brilliant that it’s been ranked The Greatest Song of All Time. But it needed… something. An organ.

Al Kooper was told to get in there and figure out an organ riff.

He balked. He’d never really played the organ. On the other hand, as a friend of his once told me, “What can’t Al play?”

You know what he did — you can hear him right at the beginning, neatly framing the recording.

Kooper moved on to a blues band, and then he started dreaming of a group that was as tough as a blues band, only backed by horns. And he formed Blood, Sweat & Tears.

Blood, Sweat & Tears fused soul, jazz and rock in a way that wasn’t “progressive” or “cool.” The secret was the songwriting — in addition to six songs by Kooper, there were contributions from Randy Newman, Harry Nilsson, and Gerry Goffin/Carole King. The album had structural integrity; it began with an overture and ended with an “underture.” And it had those supertight, superfine horns.

Critics raved. Audiences swooned. The album rose to #47. There were no hit singles. [To buy the CD from Amazon and get a free MP3 download for the insane price of $6.98, click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

Al Kooper left the group after the first album, and the band went, as they say, in a different direction — including, in 1970, a tour of Eastern Europe under the sponsorship of the State Department. (You may imagine how well that went over with the long-haired, stoned music lovers of that era.) Naturally, the sucky commercial version of Blood, Sweat & Tears made a fortune from its hits — and is the band you know as Blood, Sweat & Tears, if you know it at all.

Kooper? He discovered Lynyrd Skynyrd and produced their first three albums. (Some of the hits on those records; “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Saturday Night Special” and “Free Bird.”) Since then, he’s popped up here and there, gifted and irascible as ever.

It’s another measure of this group’s unacknowledged greatness that there’s only one song from “Child Is Father to the Man” on YouTube. Happily, it’s the most passionate song on the record: “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know.” Listen:

My brother and I saw the original Blood, Sweat & Tears once. It was the spring of 1968, and even though there was a war raging, the night was so fine you couldn’t help but feel optimistic. The band was playing in a club in the Village, and from the start, the place rocked. Every song had something smart — I fondly recall the grunt Al Kooper made after he sang the line “I could be President of General Motors, or just a tiny grain of sand” in “I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know.”

The song ended. There was some sort of conference on the stage, and then Kooper announced that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot in Memphis.

“Oh my god, they killed Moses,” my brother said.

“We gotta get out of here,” I said, and we hustled home before any bad shit could start.

There’s a connection between music and personal history; we can always remember where we were when X or Y happened. Kooper, King, that song — it’s a triad for me.

I’ll never be able to listen to this album and only hear the wonderful music. Lucky you. You can.

BONUS VIDEO

Al Kooper. 1995. No loss of power.