Books |

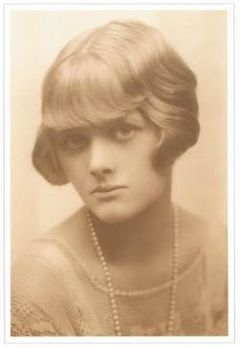

Daphne du Maurier

By

Published: Jul 26, 2015

Category:

Fiction

She wrote “Rebecca.” “The Birds.” “Jamaica Inn.” “Don’t Look Now.”

I’m fairly sure you’ve seen some of the films adapted from those books.

Hitchcock’s film of “Rebecca” — the first he made in America — was designed to be a major success. The producer was David O. Selznick, who made “Gone with the Wind.” He surrounded Hitchcock with so much talent that the film had 9 Academy Award nominations in 1941. It won two Oscars, one for cinematography, one for Best Picture. And, in his adopted America, Hitchcock was on his way.

I’m almost sure you haven’t read “Rebecca.” Too bad. It has style and story to burn. The opening:

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge-keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spokes of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited. No smoke came from the chimney, and the little lattice windows gaped forlorn. Then, like all dreamers, I was possessed of a sudden with supernatural powers and passed like a spirit through the barrier before me. The drive wound away in front of me, twisting and turning as it had always done, but as I advanced I was aware that a change had come upon it; it was narrow and unkempt, not the drive that we had known. At first I was puzzled and did not understand, and it was only when I bent my head to avoid the low swinging branch of a tree that I realized what had happened. Nature had come into her own again and, little by little, in her stealthy, insidious way had encroached upon the drive with long, tenacious fingers. The woods, always a menace even in the past, had triumphed in the end…

[To buy the book of “Rebecca” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Hitchcock was fond of du Maurier’s Gothic suspense novels. In l939, he directed the film of "Jamaica Inn." In 1963, he made “The Birds.” Not that he had any great respect for her books — or, for that matter, any writer’s work. For Hitchcock, du Maurier merely created situations that he could turn into horror movies. She, predictably, was horrified.

She had much better luck in the early 1970s, when Nicholas Roeg directed Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland in an adaptation of her novel, “Don’t Look Now.” You may remember: A married couple. One of their children has died. They’ve come to Venice. There’s a very hot sex scene that shows them getting dressed, after. A blind woman who has other ways to “see” assures the wife that their child is fine and happy and with them right now. And then it gets weirder.

Like most of you, I’m sure, I had no idea that du Maurier had written “Don’t Look Now”. Then I stumbled upon “Don’t Look Now: Selected Stories of Daphne du Maurier.” [To buy the book from Amazon, click here.] What a pleasant surprise! On the surface, du Maurier is a very conventional writer; imagine Edith Wharton with a flair for ghosts and sudden frights. But stay with her and she’s quite spooky — even though you know a twist is coming, she still fakes you out. And spooks you.

“Don’t Look Now” uses the unreal city of Venice to suggest a larger unreality. The grief of the married couple — easy to identify with — becomes secondary as the atmospherics of canals and churches creep in like a night fog. A blind seer, a dwarf, a sighting of the wife when she’s allegedly in London — du Maurier builds her improbable story carefully, until the unlikely starts to look like the only possibility.

Then comes “The Birds.” Her story could not be more different from Hitchock’s. His version is set in California. As is his obsession, there’s a cool blond with hot passions at the center of his story. She’s brought a man with her, and it seems to others that something in their relationship has caused the birds to go crazy and attack people. Like this:

du Maurier sets her story in England in a region of coastal farms. Her main character is a disabled, part-time farm worker. He’s a simple man; the first few bird attacks leave him confused and hoping for an explanation on the radio. But winter comes on suddenly — “in a single night” — and the birds are soon attacking London, maybe all of Europe. Why is this happening? Someone suggests “the Russians.” The workman doesn’t care about causes. He’s trying to save the lives of his wife and children, he’s thinking about stronger wood over the windows.

The escalation is intense — one resourceful man against nature gone wild — and if you don’t read this story with some sense of an ecological holocaust, I think you’re missing the boat. How prescient of du Maurier! And how delicious are these sentences: “They [the birds] had not learnt yet how to cling to a shoulder, how to rip clothing, how to dive in mass upon the head, upon the body. But with each dive, with each attack, they became bolder.

Other stories, other chills. A British ship crossing the Atlantic during the U-boat attacks of World War II has an unlikely escort. A woman goes out of her house for a few hours; when she returns, others are living there. A man goes on a date with a woman whose hobby turns out to be murder. And in the scariest story of them all, a rich woman has eye surgery that gives her the ability to see people as they really are — that is, with heads of snakes and weasels and other animals. That is, she sees their character clearly. And then she sees her own face….but no spoilers here.

You can see scarier stuff at the movies. That’s not the point. These are stories for nights when you’re alone, when you wish you’d had that creak in the stairs fixed. The wind makes a shutter slam shut, and you recoil. And then it’s very quiet, and there you are, with just your thoughts — yes, this is the book you want on one of those nights.