Books |

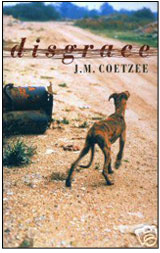

Disgrace

J.M. Coetzee

By

Published: Jan 12, 2009

Category:

Fiction

Only one writer has ever won England’s Booker Prize twice, and the second time J.M. Coetzee won it was for "Disgrace." A few years later, a poll of "literary luminaries" chosen by The Observer newspaper in London named “Disgrace” as the "greatest novel of the last 25 years" written in English outside the United States. And in 2003, Coetzee won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Coetzee is not a writer who craves honors — or even social gatherings. A colleague has recalled that, in a decade, Coetzee laughed just once. Another noted that, at several dinner parties, Coetzee never spoke. His Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech? It’s about Robinson Crusoe. (You figure it out.) His Nobel Prize Banquet Speech is just 248 words, and it reveals almost nothing of the man:

My mother would have been bursting with pride. My son the Nobel Prize winner. And for whom, anyway, do we do the things that lead to Nobel Prizes if not for our mothers?

His fiction is characterized by its tautness — with Coetzee, there’s never a wasted word. Waiting for the Barbarians, an early novel and one of the Books That Changed My Life, is just 192 pages. “Disgrace” is 220 pages, and the velocity is equaled only by the precision. [To buy “Disgrace” from Amazon, click here.]

Here is the first paragraph:

For a man of his age, fifty-two, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well. On Thursday afternoons he drives to Green Point. Punctually at two p.m. he presses the buzzer at the entrance to Windsor Mansions, speaks his name, and enters. Waiting for him at the door of No. 113 is Soraya. He goes straight through to the bedroom, which is pleasant-smelling and softly lit, and undresses. Soraya emerges from the bathroom, drops her robe, slides into bed beside him.`Have you missed me?’ she asks.`I miss you all the time,’ he replies. He strokes her honey-brown body, unmarked by the sun; he stretches her out, kisses her breasts; they make love.

That’s quite a lot of information. And because it’s about sex, it’s information that grabs our attention. What will happen between David Lurie and Soraya? Not much. She’s gone by page 8. On page 9, Lurie’s thinking seriously about castration — an end to sex. On page 11, this aging literature professor at a South African university, whose sexual interest apparently excludes older women, starts a conversation with Melanie Isaacs, a student in his Romantic Poetry course. By page 16, they’re lovers.

Well, we know where this is going — we’ve seen "The Blue Angel," in which a professor makes a fool of himself over young, amoral Marlene Dietrich. That’s rich material; for any number of novelists, it’s a book. For Coetzee, it’s just the set-up; by page 59, he’s been charged with sexually harassing Melanie and falsifying her grades.

Lurie appears before a faculty committee and admits the affair, but refuses his colleagues’ entreaties to apologize. He loses his job and, in disgrace, drives to his daughter’s five-hectare farm in the Eastern Cape. Lucy Luria’s life is rough, but it suits her: “dogs and a gun, bread in the oven and a crop in the earth.” And, soon, it suits her father — although the professor does not, as his daughter does, believe there is only “the life we share with animals”, he finds it a relief to do chores.

South Africa in the early days as a free country — did you think whites and coloreds were singing folk songs around a campfire? Not in the Eastern Cape. Three thugs attack the farm, beat David, gang-rape Lucy. Now both father and daughter are disgraced.

This is nasty stuff, and nastier because it’s not personal — large forces are in play, the Lurias just happen to be the victims. Coetzee emphasizes the nastiness. Indeed, if there’s a saint in the novel, it’s Lucy’s friend Bev, who spends her days putting down unwanted dogs. She does this with love and tenderness, but no one is fooled — her business is death.

Is this a bleak and cheerless book? Or does it suggest that we find nobility in staring disgrace down? That’s for you to decide. But first, you’ve got to be willing to read it. Let me make the case for that. First, read “Disgrace” as a corrective to all those novels with “happy” problems — marriages that might yet be repaired, family dramas that could be satisfactorily resolved, tales of animals that teach their owners the meaning of love. Second, read it for the ideas, which are so neatly inserted you always feel you’re reading an action novel, even a thriller; you never feel you’re really being asked to think about Wordsworth and Byron and whether the real origin of speech is song. And, finally, read it because Coetzee, like any great artist, is what Ezra Pound described as “the antenna of the race” — what he sees now, you may come to see later.

In the late 1990s, as he was writing “Disgrace”, this is what Coetzee saw: "One gets used to things getting harder; one ceases to be surprised that what used to be as hard as hard can be grows harder yet." There is absolutely no comfort to be found in that prospect — none. But there may be declining comfort for us all in the months and years ahead, and sticking our heads in the sand won’t change that in the least. Coming to terms with bleakness and finding what inner resources we have just might.

If you’re willing to get serious — really, deeply serious — “Disgrace” is your book.