Movies |

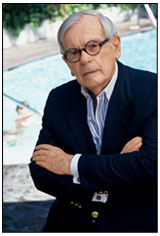

Dominick Dunne: After the Party

By

Published: Jan 01, 2008

Category:

Documentary

Vanity Fair is a media brand so big that it can, if you’re involved with it, dwarf everything else in your professional life. I know. I resigned in 1993 after six years as a contributing editor — and even now, all these years later, people come up to me and say, “Love your stuff in Vanity Fair.”

Imagine how it must have been for Dominick Dunne, who was, for more than two decades, the magazine’s brightest star.

You can, in fact, see how it was, in the first minute of a documentary called "Dominick Dunne: After the Party." [To buy the DVD from Amazon, click here.]

He’s on a stage, giving what others would call a lecture and he’d call telling stories. This one is about Frank Sinatra, in a time long past, when Dunne was married and living in Beverly Hills and working in the movie business.

“Frank Sinatra picked on me,” Dunne begins.

The audience titters.

Dunne goes on to tell a story about a night at the Daisy, a club in Beverly Hills. He and his wife Lenny are there. Frank Sinatra and his crew show up. Nick and Frank go way back, but they’re no longer friends — Sinatra, says Dunne, likes to tell Lenny Dunne that she’s married to a “loser”. Now Sinatra sends the maitre d’ over. “I’m so sorry about this, Mr. Dunne,” the man says, “but Mr. Sinatra made me do it.”

And with that he punches Dunne in the face.

The audience laughs.

“I was the amusement for Sinatra,” Dunne continues. “My humiliation was his fun.”

The audience, still not getting it, laughs again.

I can understand that laughter — these fans of his articles and novels don’t know how to process the information they’re being given. That’s because they know Dunne only as Mr. Vanity Fair, a crown prince of winners. They’re clueless about the first half century of his life, which is about out-of-control ambition, deep insecurity and the constant threat of humiliation. And they have no idea how his worst fears came to pass, how he drank and drugged and lost everything.

So they laugh.

“I hated him from that moment on,” Dunne says, and now the audience is with him, because they are very familiar with Dominick Dunne as a professional hater, a scourge of the rich and criminal, a judge with a pen. O. J. Simpson, Claus von Bülow, the Menendez brothers, Phil Spector — regardless of the legal verdict, Dunne convicted them all.

The big surprise of this documentary: Dunne convicts himself.

“The reason I can write assholes so well,” he says, looking right into the camera, “is that I used to be an asshole.”

This is riveting viewing — I dare you to look away — but that is not to say “After the Party” is amusing. It’s something else: a man coming clean, ripping off layer after layer of pretense, telling the truth about himself in a way you never expect from any member of the America celebrity class.

The story is no puzzle — if Dunne’s account is remotely accurate, the recipe for early success and midlife failure was developed at home. Here’s Dunne:

My father was this famous heart surgeon, a wonderful man…but there was something about me that drove him crazy. He mimicked me, he called me sissy. It may seem like nothing now but it’s awful to hurt a child. It’s a terrible thing. My opinion of myself was nothing…I believed I was everything he said.

Dunne was, by his own account, an unlikely hero in World War II — could that have anything to do with the memory of his father whipping him? And his obsession with being accepted at the highest level of Hollywood — could there be any better way to show his father he was worthy? And the movies he produced — who wouldn’t be proud of making Al Pacino’s first movie and the adaptation of the best-known novel of his sister-in-law, Joan Didion?

When the crash came, it was total: no marriage, no career, no money. Dunne retreated to a one-room cabin, without telephone or television, in the Cascade Mountains of Oregon, and, at 50, began to write. A few years later, his daughter, Dominique, was strangled to death by a former boyfriend. A chance meeting with Tina Brown led to an invitation to write about the trial for Vanity Fair. Here’s Dunne:

I had never attended a trial until my daughter’s murder trial. What I witnessed in that courtroom enraged and redirected me. It wouldn’t be necessary to hire a killer to kill the killer of my daughter, as I had contemplated. I could write about it.

Tina Brown published that piece and offered Dunne a job. “I couldn’t sign that contract with Vanity Fair quick enough,” he says. “I was 59 at the time.”

For most of the film, the camera stays tight on Dunne, as the Irish Catholic raconteur builds the case against himself. There are a few witnesses for spice — his son Griffin, Liz Smith, Tina Brown, producer Bob Evans, Joan Didion — but they don’t exonerate him so much as they confirm the accuracy of his memories.

“I had to admit, I cried a lot,” Dunne said after his first viewing of the film. “It really shows my life completely, the fakery of the early me — and I’m not embarrassed a bit.”

I became Dominick Dunne’s friend in 1975. We met as he was about to take a high dive into the failure pool, re-connected after his daughter’s murder, were colleagues at Vanity Fair, friends right to his death. I mention our relationship not as a name-drop — okay, not just as a name-drop — but because it means I knew pretty much everything in this documentary.

Knowing and seeing are very different, however, and the movie hit me hard. But if I cried — and I did, and you will too — I also laughed and cheered. Because as much as we like the “Rocky” myth of a nobody getting somewhere, we also thrill to the story of a guy who got somewhere, lost it and fought his way back — and now makes his living and his life by trying, as best he can, to tell the truth.

Sometimes what happens after the party is better than the party.