Books |

Exiles

Michael J. Arlen

By

Published: Aug 15, 2021

Category:

Memoir

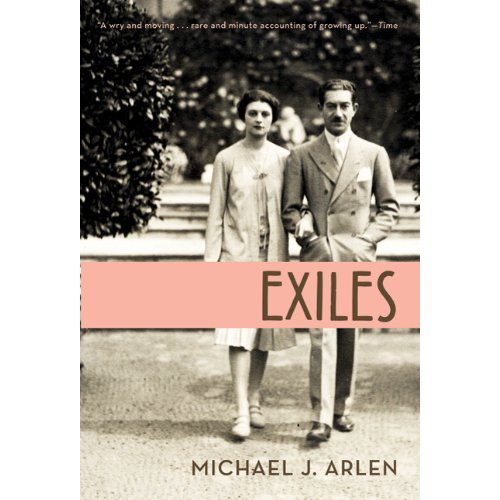

The photograph on the cover doesn’t suggest how short they both were, how small. All you notice is their elegance, her pleated skirt just so, his hands shoved casually in the jacket pockets of his natty double-breasted suit. Their gaze is direct. Confident. Elegant.

But there’s something the photo doesn’t catch. Michael Arlen — author of a novel called “The Green Hat” — may be more successful than his friends F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. But Michael Arlen isn’t who he looks like; he was born Dikran Kouyoumdjian, an Armenian. In London, he won’t fit in. Ditto in New York and the South of France. And his wife isn’t exactly who she looks like either.

Exiles. So their son, Michael J. Arlen, thinks of them. Exiles? How can that be — they had it all. Michael Arlen’s photograph was on the cover of Time Magazine. In the South of France, he owned the very best speedboat and hired a driver for it. Willie Maugham and Winston Churchill came for lunch. “The day he arrived in Chicago, the Daily News ran a front-page story — saying that he had arrived in Chicago.” But when the fame went away, he was beached. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Michael J. Arlen gets the glitter. And, even more, the courage that kept his father going. He tells the delicious story of his father running into Louis B. Mayer, the movie mogul, at the “21” Club in New York. Arlen had just arrived from England; Mayer asked about his plans. “I was just talking to Sam Goldwyn,” Arlen said — which was true, he’d just encountered Mayer’s rival, who had urged him to buy horses. Mayer asked, “How much did he offer you?” Arlen thought fast: “Not enough.” A few minutes later, he had a 30-week contract as a writer at MGM for $1,500 a week.

Michael Arlen wants to be a father to his son, so he invites the boy out to California. There’s a weekend in Santa Barbara. At Clark Gable’s house. Only Gable’s not there. It’s a house party of tanned men and attractive women. Of cigarettes and liquor. And a terrible moment when his father is talking — and nobody’s listening. Later, the boy finds his father sitting by the pool. “I was out here a long time ago,” his father said. “We used to play tennis. Thalberg — he always wanted to talk about literature.”

These are people of a breed long vanished, and their lives will seem strange. The big duplex apartment. Long lunches. Cocktail time. Sitting in the library at night, reading and drinking. And the sadness: young Michael hearing his father in the afternoon, not writing, just pacing, pacing. Here’s his mother, dying, her last words coming across decades, from Monte Carlo: “Let’s take the road down by the sea this time. It will be longer, but nothing really starts until ten anyway…”

Other stories are right out of Salinger or John O’Hara. Young Michael, at boarding school, not winning and then winning a history prize. Michael, a senior at Harvard, desperate to marry his 19-year-old girlfriend. Their parents don’t approve. Oh, the agony, “the back-seat-of-the car fifteen floors above Park Avenue.” And, a little later, Michael, frustrated, making a phone call and getting a job in the Henry Luce empire.

I haven’t mentioned the writing. I think this book is right up there with the stories of James Salter, but some will find it falsely casual, like a very self-conscious voice talking. Maybe. Consider where Michael J. Arlen came from. And consider, too, that this is an elegy, and elegies should shine. Like this:

They were both of them beautiful. They were also, both of them, in a kind of exile, and sought to find a home, a country, in one another, and very nearly did, came as close to it as maybe it is possible to do, but they were each so deep in exile when they met — and how would they have known that? My mother, so seemingly established — a title, even, money somewhere in the background, big houses, gardens, furniture, wax for the furniture, polish for the silver, manners, style, and more than manners or style, a seeming feel for independence…. and seeking to escape from her (still unknown) exile, from all those mannered, self-protective people into this unusual man’s vitality, life, imagination, energy — well, as with many men, it turned out to be a fragile, an especially fragile kind of energy. So delicate, really. Too delicate. But that was for later, for much later. It was later that they found these things out, or didn’t find them out, just lived them, lived under them. In the beginning, though, it must have been lovely….

Tastes differ. But this writing never fails to thrill me.