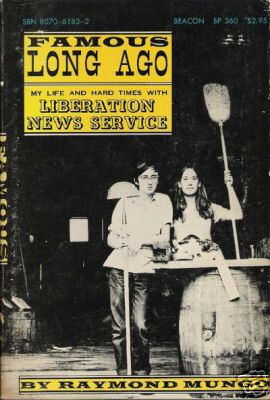

Books |

Famous Long Ago: My Life and Hard Times With Liberation News Service

Raymond Mungo

By

Published: Jun 28, 2012

Category:

Memoir

If Ray Mungo had grown up like the other kids in Lawrence, Massachusetts, he would have become “a laborer in a paper or textile mill, married and the father of two children, a veteran of action in Vietnam, and a reasonably brainwashed communicant in a Roman Catholic, predominantly Irish parish.

Instead, he became “a lazy good-for-nothing dropout, probably a Communist dupe, and lived on a communal farm way, way into the backwoods of Vermont.

And so he asks: “What went wrong?”

Nothing went wrong.

I met Ray Mungo in 1969, when I was a desperately unhappy graduate student and he was a self-deposed king of the “underground’ press, living in glorious exile on a communal farm in Vermont. His life was good. And it looked good. Weeks later, I was living on a farm in Western Massachusetts.

To know Ray Mungo is to love him. He is physically tiny, intellectually large, politically astute, emotionally wise. And funny — young firebrands are notoriously serious, but Ray always got the joke.

All of that is on display in “Famous Long Ago: My Life and Hard Times With Liberation News Service,” which Ray wrote to pay the mortgage in 1969. Robert Redford optioned it for the movies. Cult status descended. And now, all these years later, it’s back. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here.]

What’s it about?

A scholarship student at Boston University becomes, in his freshman year, a Marxist. Sophomore year: “Somebody (God bless him) turned me on to dope.” Junior year: “I traveled around the country participating in demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, and lived from day to day, smoked a lot of dope and fornicated every night. It was glorious.” Senior year: “I edited the college newspaper and put a lot of stuff about draft resistance, the war, abortions, dope, black people, and academic revolutions in it. Which, even though it was 1966, people seemed to think was pretty far-out stuff indeed.” (It was. Mungo was probably the first college newspaper editor to call for the impeachment of Lyndon Johnson.)

Mungo had a “fat fellowship” at Harvard. Instead, with a madman named Marshall Bloom, he started a radical news service — a predecessor of The Huffington Post, only with major cojones. In its first incarnation, in Washington, it was a flop:

Our glorious scheme of joining together the campus editors, the Communists, the Trots, the hippies, the astrology freaks, the pacifists, the SDS kids, the black militants, the Mexican-American liberation fighters, and all their respective journals was reduced to ashes. Our conception of Liberation News Service as “democratic organization,” owned by those it served, was clearly ridiculous; among those it served were men whose very lives were devoted to the principle that no organization, no institution, was desirable… At any rate, it was clear on first meeting our constituency that Liberation News Service was to be an uneasy coalition.

Mungo and Bloom moved LNS to New York. They fared no better: “Vulgar Marxists” kept getting in the way. So in a daring midnight theft, Mungo and Bloom “stole” the printing presses and fled to their new farms. The pissed-off Marxists followed. Mayhem ensued.

Many adventures followed; they were, by turns, absurd, profound, telling. And tragic — after Mungo finished the book, Marshall Bloom connected a hose to the tailpipe of his battered sports car, and, in Mungo’s words from the dedication, “left us confused and angry, lonely and possessed, inspired and moved but generally broken.”

I value this book highly because it’s real. It’s how it happened. How it felt. The dreams. The failures. The need to adjust ideals, or not. Many books about the ‘60s are alleged to deliver all this. I can’t think of another that really does.

A new epilogue follows. Judge for yourself.

Epilogue: beyond the end

Thank you, dear friend, for reading “Famous Long Ago,” which I wrote at age 22 in 1968 and ’69 and never really imagined I’d live long enough to look back on. When I signed the book contract, my intention was to raise money for the mortgage payment on our rural Vermont commune, Total Loss Farm, to which we had migrated from LNS only months earlier. The publisher’s advance was small, the publicity and advertising budget nil, and the whole thing just another cri de coeur in an era of passionate youthful outbursts. I was stoned every minute while writing it. It was kid stuff. But it struck a nerve and the story survives.

Hey, 1968 was a helluva time to be a kid. You had to be there. If you weren’t, and you’ve heard it was such an orgiastic gas, be advised. The 1960’s were really hard for young people. Come on, we were getting drafted into Vietnam and busted for joints, arrested for looking too weird. Women were literally second-class citizens, gays and lesbians were in hiding, afraid for their lives, interracial marriage was still against the law in some states and birth control devices illegal in Massachusetts, where religion trumped common sense, and we just got no respect, y’know?

If you were aware of reality, you were protesting – everything, the government, the war, the university, your parents, the draft, sexual repression, big business, suffocating employment, blatant racism, rampant capitalism, cultural moronism. We were screaming in the streets.

We were poor, squalidly so, but not willing to work for “the man” and cooperate with the murderous “system.” Not afraid to speak our minds. Foolish perhaps, but not paranoid. We needed and benefited from the support of those elders who shared our views.

There are surely some parallels between the ‘60s and the younger generation of the now/newish millennium. The absence of meaningful jobs, for one thing. Economic uncertainty. The nation at war, but nobody knows why the hell. Distrust of the establishment. Cultural disconnect from one’s forbears. The feeling that if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself. The instinct to start up your own venture rather than looking for job slavery. The realization that you are your own media, each one a publisher. The instinct to connect with your friends in a network or group effort. Communes are even back in style, in a fashion.

I hope you didn’t try to learn anything from the book, for there was no message intended. It was just an extended rap, let’s say. For all that, I seem to have lobbed one strong opinion after another, and still believe in them. The book morphed into an artifact for history classes, no doubt because the important events and personalities of that time are now part of our shared heritage, and it was written in the quick moment of those events and from the heart, kinda like a diary of the doomsday generation.

We really weren’t sure whether the world was coming to an end or not. Despite our best efforts and huge struggles to reform the system, somehow Nixon got elected president in1968. So we did our best to make fun of it and escape from it.

There’s plenty of embarrassment for me in FLA. College kids are called “pimply and fatuous and awful,” lesbians are “dikes,” African Americans are “spades.” I’m sorry! Here we considered ourselves the ultimate in New Age thinkers, too. Racism was abhorred, but male chauvinism and internalized homophobia were taken for granted in our radical cohort. We weren’t as cool as we thought we were. But the young are due their self-confidence, and we were damn sure we were right and the powers-that-be were wrong. Give peace a chance.

You can also find multiple other accounts of exactly what went down at LNS, many of them well documented in John McMillian’s authoritative book Smoking Typewriters, the best account of the Vietnam era underground press yet undertaken. I can’t assert that every single fact in “Famous Long Ago” is accurate, but it’s all true, I swear. It’s the truth as I experienced it. Ask any honest historian and she’ll tell you all memory is perception. Details may differ, but the big picture is intact. We faced a world in flames.

Friendship remains a constant throughout these generations. I hope you enjoyed this journey as I, much of the time, enjoyed putting it down for you. I’m still with you, even if only through this contact. Facebook has remade “friend” into a verb, and its definition of a “friend” is basically someone who is not your enemy. (OK, OK, Thoreau already said that a hundred years earlier.) But we have something special, you and I. We have lived through the Apocalypse, skating on thin ice.

Welcome home.