Books |

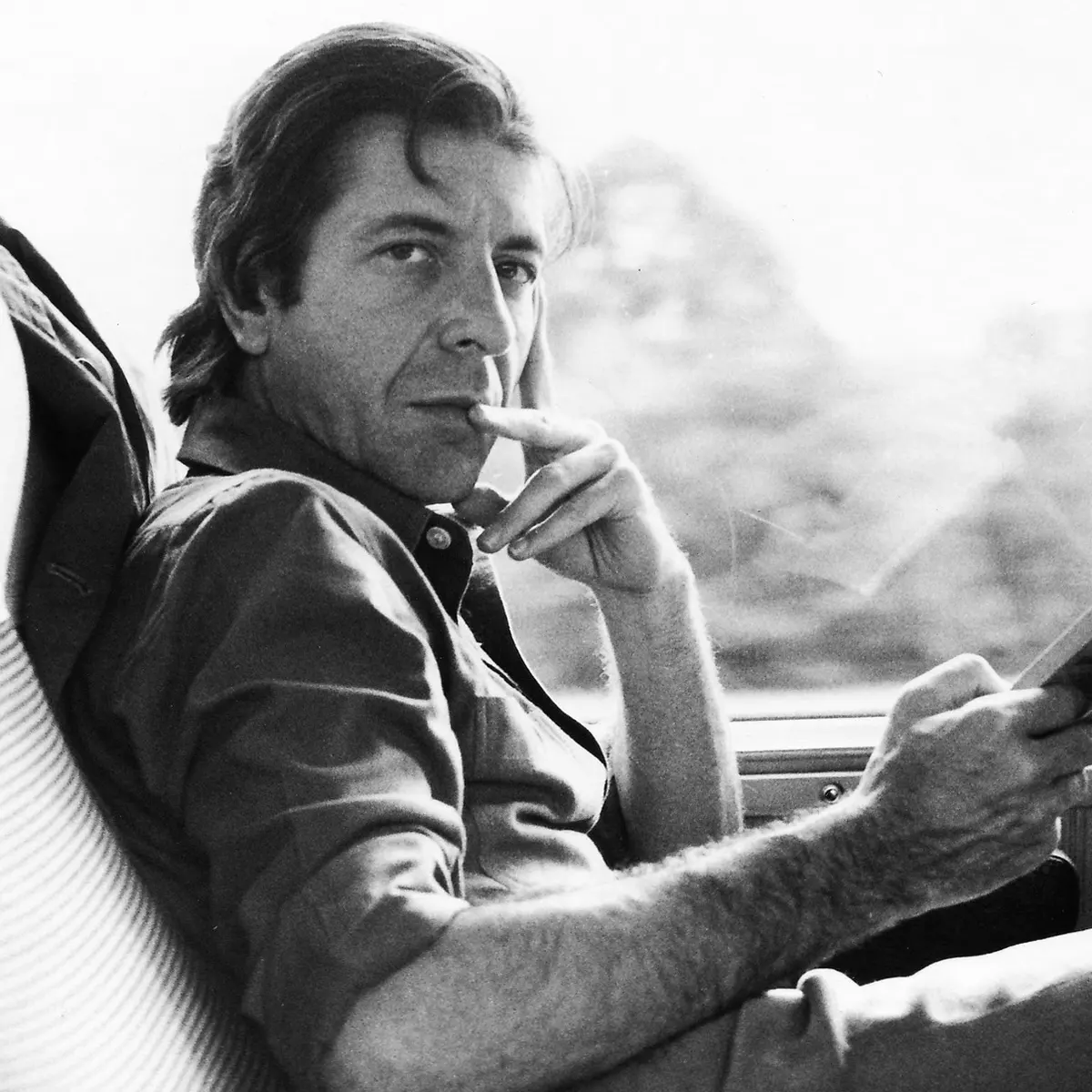

Leonard Cohen: The Favorite Game

By

Published: Sep 21, 2021

Category:

Fiction

In some homes, Leonard Cohen’s birthday is like the birthday of a saint, mostly for the music — click here for an appreciation and a primer. But Cohen didn’t set out to be a singer/songwriter. He started as a poet. And a novelist. Music was what he turned to when he couldn’t make a decent living as a writer.

Beautiful Losers, published in 1968, is the novel you may have heard of. Its subject is murky — a French-Canadian nun, dead 300 years, is being considered for sainthood — and the writing is a lush, dense thicket. There’s no bigger Cohen fan than this writer, but I found it tough going. More accurately, it’s an incoherent drug trip. I have no longing to revisit it.

But “The Favorite Game” — Cohen’s first novel, published in 1963, when he was 29 — charmed me 60 years ago, and still does. Now that he’s gone, it’s the closest thing we’ll have to a memoir of Cohen’s youth. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here.]

Cohen’s stand-in, Lawrence Breavman, is a brooding Jewish boy learning to make his way in the world by sucking experience dry. His education is written on the bodies of women, then erased when he moves on. And he always moves on. You may find this obnoxious. Standards were different then. Or maybe male writers felt no need to be careful.

Start in Montreal, where the Breavmans are rich. Which is not to say happy, or close to. Mr. Breavman is fat and ill; Mrs. Breavman is a major league neurotic. Lawrence spends as little time with them as possible — he and his best friend, Krantz, are into deep explorations of the world, which starts and ends with girls.

At 11, the girls of youth sprout breasts, and Breavman “marveled that he had ever kissed the mouth that now mastered cigarettes.” He finds a pair of fur gloves; masturbation becomes sublime.

Later, there is hypnotism: “He unbuttoned his fly and told her she was holding a stick.” Still later, college: “He couldn’t believe his hands. The kind of surprise when the silver paper comes off the triangle of Gruyere in one piece.”

From seventeen to twenty, Tamara is his mistress. She’s the woman he’ll always return to, the woman who accepts every word and touch. Though it’s really not that simple — “they were cruel to one another.” Tears. Silences. “He hated himself for hurting her and hated her for smothering him.” Bed became “like a prison surrounded by electric wires.”

Graduation. The inevitable breakup with Tamara. Long midnight car rides with Krantz. Breavman’s first book of poems. His undeserved reputation: “Canadians are desperate for a Keats.” He reads for every group that will invite him, “slept with as many chairwoman as he could.” And flees to New York.

Shell is from Connecticut. Rich. WASP. Smith College. Married at 19 to Gordon Ritchie Sims. Who, in five years, cannot bring himself to sleep with her. She is sitting with her newly acquired lover when Breavman spots her. He fills napkins with poems. Stands before her and declares her beautiful.

“I’m married,” she says.

“No, no, I don’t think you are.”

So it begins, the romance the entire book has been pointing toward. Music and poetry, long walks and intimate silences. How does it end? What is the favorite game? What does it have to with Shell?

And more: What is the price of tenderness? How do we stop running — running from, running toward? If language is such a blessing, why do we use it to deceive? When innocence departs, where does it go?

Sound familiar? It should — these are the issues of our romances. Our glory, our shame, unspooling before us. Cohen has no answers. But he has a way of presenting the questions that will — for some readers, anyway — pierce the heart.