Books |

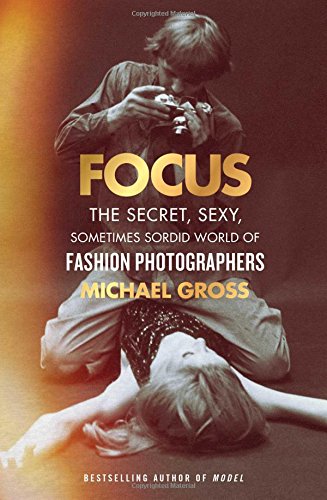

Focus: The Secret, Sexy, Sometimes Sordid World of Fashion Photographers

Michael Gross

By

Published: Jul 10, 2016

Category:

Fashion

Michael Gross is a professional shit-stirrer. Almost alone among writers who chronicle the rich and glittering in New York, he doesn’t write books that endear him to his subjects. Does he get asked to chic dinners at the homes of the 1%? I’m thinking it rarely happens. I’m thinking he doesn’t care.

Michael Gross takes on the Swells where they live. Literally. 740 Park: The Story of the World’s Richest Apartment Building gets you past the lobby of that fortress and gives you passages like this: “I remember Mrs. Parrish saying that all this money had come from liquor, so why don’t we paint it the color of whisky?” said decorator Mark Hampton. And Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret Story of the Lust, Lies, Greed, and Betrayals That Made the Metropolitan Museum of Art takes you into the boardroom of New York’s cultural elite. I’m not addicted to stories like that, but I was completely riveted by the effort of Annette de la Renta to discredit Michael Gross because of some unpleasant facts about her on pages 458-462 of a dense, 485-page text. And it was my pleasure to take his side against them.

Now we have “Focus: The Secret, Sexy, Sometimes Sordid World of Fashion Photographers,” 375 pages of more-than-you-thought-you-wanted-to-know about the many men and a few women who have filled the pages of magazines with images that rarely had anything to do with the clothes worn by the models. Many of the photographers he profiles are dead. If not, they might die of embarrassment — or would, if they could assess their behavior in a context that resembles life as you and I experience it.

Focus is two books in one.

The first is a terrific, serious, exhaustively complete history of post-World War II fashion photography, media and the fashion industry. It explains how photographers became more important than editors and advertisers became more important than editors — how Vogue, Bazaar, Elle and others became more like catalogues than editorial statements. “Nobody’s innocent,” someone says, and that’s an understatement — in this world, everybody’s got a hand out. And everybody in the business knows it, and for how much. Only the public is in the dark. (In the art world, they know better — the real money is in art photography.)

Gross has a cool-eyed view of this transformation: “[Fashion photography] isn’t gone. It’s just different. These were its glory days.”

Why should you care? Precisely because this stuff is ephemeral. Gossamer. And it’s in that zone that you can see the first vibrations of changes that will ripple across the wider culture. Avedon vs. Penn: the differences matter, and Gross explains those differences, and you see how ambition and background and opportunities create something worth knowing about — something like art. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

The second book is attention-getting and borderline disturbing and may turn you off or on, depending on how you relate to drugs, the exploitation of women and any definition of beauty that goes no deeper than skin. As Gross writes:

Fashion photographers, the Svengalis who shoot editorial and advertising images of clothing and mold and elevate the stunners who star in them, are figures in the shadows who make those in front of their cameras glow like members of some special, enlightened tribe. But the world they inhabit has striking contrasts: it appears beautiful, but just beneath the pretty surface, like the images they create, the reality can be murkier, often decadent and sometimes downright ugly.

In that second book, you read about shockingly well-endowed photographers whose studios would be incompletely furnished if they didn’t have mattresses. You read about 24/7 drug use that should kill anyone and did kill any number of these photographers. By the time you get to the party at Bill King’s, where “a blond poster girl for wholesome California pulchritude”— you won’t have trouble thinking of a few names — sat on two sinks next to two men, and both her hands were busy, nothing surprises you. As someone who was there recalled, “It was so beautiful.” And maybe it was — certainly compared to a Kardashian sex tape.

Did I enjoy that second book? From time to time. The first book? I marked and underlined like crazy.

EXCERPT: CHAPTER 1

A chilly rain was falling on November 6, 1989, when several generations of New York’s fashion and social elite gathered in the medieval-sculpture hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a memorial celebrating Diana Vreeland, the fashion editor, curator, and quintessence of self-creation.

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, for whom Vreeland was a fashion god-mother, and Lauren Bacall, who’d been discovered by her, both arrived alone. Dorinda Dixon Ryan, known as D.D., who’d worked under Vreeland at Harper’s Bazaar, was seated next to Carolyne Roehm, one among many fashion designers in attendance. Mica Ertegun and Chessy Rayner, the society decorators, sat with Reinaldo Herrera, holder of the Spanish title Marqués of Torre Casa, whose family estate in Venezuela, built in 1590, is said to be the oldest continuously inhabited home in the Western Hemisphere.

One of Vreeland’s sons delivered a eulogy, as did socialite C. Z. Guest; Pierre Bergé, the business partner of Yves Saint Laurent; Oscar de la Renta, the society dressmaker; Philippe de Montebello, then the museum’s director and Vreeland’s final boss when she ran its Costume Institute; and George Plimpton, who cowrote her memoir, D.V. But the afternoon’s most telling fashion moment came in between Montebello and Plimpton, when photographer Richard Avedon, who’d worked with Vreeland from the start of his career, took the stage.

Avedon was a giant in fashion and society, an insider and an iconoclast, a trenchant critic of the very worlds that had made him a star, arguably the most celebrated photographer of the twentieth century. Never one to mince words or spare the feelings of others (“Oh, Dick, Dick, Dick is such a dick,” a junior fashion editor once said), he used his eulogy as a gun aimed at Vreeland’s latest successor at Vogue, Anna Wintour.

Though he never once mentioned her name, he sought to wound Wintour, who’d arrived at the memorial with her bosses, the heads of Condé Nast Publications, S. I. “Si” Newhouse Jr., the company’s chairman, and Alexander Liberman, its editorial director. Just a year earlier, they’d let Wintour replace Avedon as the photographer of Vogue’s covers. Only a few in the audience knew that Avedon had actually shot a cover for the November 1988 issue, Wintour’s first as editor in chief of Vogue, and that no one had bothered to alert him that Wintour had replaced it with a picture by the much-younger Peter Lindbergh. Avedon only found out when the printed issue arrived at his studio.

He never shot for Vogue again.

A year later, Avedon served up his revenge dressed in a tribute to the woman he’d sometimes refer to as his “crazy aunt” Diana. Avedon recalled their first meeting in 1945 when he was twenty-two and fresh out of the merchant marine. Carmel Snow was about to make true his short lifetime’s dream of taking photographs for Harper’s Bazaar, the magazine she edited that he’d first encountered as the son of a Fifth Avenue fashion retailer. Newspaper and magazine stories about the Vreeland memorial would linger on Avedon’s recollections of their first meeting, how he watched her stick a pin into both a dress and the model wearing it, “who let out a little scream,” he remembered. Vreeland turned to him for the very first time and said, “Aberdeen, Aberdeen, doesn’t it make you want to cry?”

It did, he went on, but not because he loved the dress or appreciated the mangling of his name. He went back to Carmel Snow and said, “I can’t work with that woman.” Snow replied that he would, “and I did,” Avedon continued, “to my enormous benefit, for almost forty years.”

But that charming opening anecdote was nothing compared to what followed. Avedon extolled Vreeland’s virtues, “the amazing gallop of her imagination,” her preternatural understanding of what women would want to wear, her “sense of humor so large, so generous, she was ever ready to make a joke of herself,” and the diligence that made her “the hardest-working person I’ve ever known…”

“I am here as a witness,” Avedon concluded. “Diana lived for imagination ruled by discipline, and created a totally new profession. Vreeland invented the fashion editor. Before her, it was society ladies who put hats on other society ladies. Now, it’s promotion ladies who compete with other promotion ladies. No one has equaled her—not nearly. And the form has died with her. It’s just staggering how lost her standards are to the fashion world.”

Sitting at the front of the audience between her two bosses, wearing a Chanel suit that mixed Vreeland’s signature color, red, with the black of mourning, the haughty Wintour, her eyes hidden behind sunglasses, gave no hint that she knew Avedon was speaking to her. But even though he saw her ascendance as a sign of the fashion Apocalypse, it’s unlikely that even the prescient Avedon could have foreseen all the other, related forces then taking shape that would, in little more than a decade, fundamentally alter the role—fashion photographer — that he’d not only mastered but embodied.