Books |

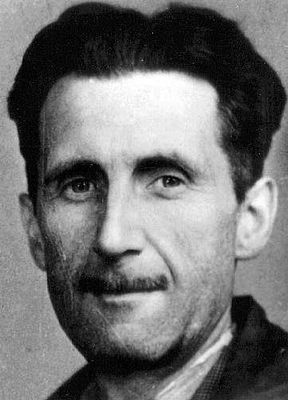

George Orwell: The Orwell Reader

By

Published: Jun 24, 2017

Category:

Fiction

SUPPORTING BUTLER: Since the start of 2023, Amazon seems to have gone on a quiet campaign to rid itself of small sites that, collectively, generate revenue worth noticing — and Head Butler no longer gets a commission on your Amazon purchases. Although this site was never designed to be a moneymaker, it was always key that it pay its production costs. And now it doesn’t. Did I appeal? Of course. But Amazon is a walled fortress; you can appeal its decisions, but it won’t respond. So…. the only way you can contribute to Head Butler’s bottom line is to become a patron of this site, and automatically donate any amount you please — starting with $1 — each month. The service that enables this is Patreon, and to go there, just click here. Again, thank you.

LAST WEEK IN BUTLER: Weekend Butler. J.J. Cale. A Pen Pal and a Director. Donbas.

—–

If you like to read entire books rather than excerpts, “The Orwell Reader: Fiction, Essays and Reportage” isn’t for you. But if you don’t really know Orwell, or had to read “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four” in your rapidly receding school years, selective reading in this collection will surprise you — many of the issues Orwell dealt with are issues facing us today. (Fun Fact: Orwell submitted “Animal Farm” to T.S. Eliot, who was then an editor at a book publisher. Here’s Eliot’s rejection letter.)

A bit of background. He was born Eric Blair. His family was distinguished; its fortunes were not. Still, he graduated from Eton, where he got a close look at the ways of the sons of England’s rich and privileged. By then, the money had run out. Instead of going on to a university, he joined the Indian Imperial Police.

His experiences abroad put him on the road to becoming George Orwell, champion of commonsense, friend to the workingman and the social democrat, enemy of orthodoxy and empire. He wore rough tweeds, drank dark tea, and rolled his own. He was wounded in the Spanish Civil War. Back in the 1930s, those were some credentials.

What most impresses me about Orwell — back when I was reading everything he wrote and thinking hard about him for my college thesis, “The Contradictions of Commitment in the Work of George Orwell” — is how well he sees both sides. Rare among English leftists, he quickly saw through the Communists and never embarrassed himself with apologies for Stalin and his stooges. See for yourself — re-read him. [To buy “1984” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition of “1984,” click here. To buy “Animal Farm,” click here. For the Kindle edition of “Animal Farm,” click here. To buy “The Orwell Reader,” click here.]

Take “A Hanging.” [Yes, it’s online, for free.] The man to be executed in Burma is “a Hindu, a puny wisp of a man, with a shaven head and vague liquid eyes.” The hangman? Also a convict — quite efficient of the Brits, huh? Here’s Orwell on the condemned men and the system that’s killing him:

…till that moment I had never realized what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man. When I saw the prisoner step aside to avoid the puddle, I saw the mystery, the unspeakable wrongness, of cutting a life short when it is in full tide. This man was not dying, he was alive just as we were alive. All the organs of his body were working — bowels digesting food, skin renewing itself, nails growing, tissues forming — all toiling away in solemn foolery. His nails would still be growing when he stood on the drop, when he was falling through the air with a tenth of a second to live. His eyes saw the yellow gravel and the grey walls, and his brain still remembered, foresaw, reasoned — reasoned even about puddles. He and we were a party of men walking together, seeing, hearing, feeling, understanding the same world; and in two minutes, with a sudden snap, one of us would be gone — one mind less, one world less.

And after? “We all had a drink together, native and European alike, quite amicably. The dead man was a hundred yards away.” At no point does Orwell, who’s nailed everybody in this piece, register his disgust — at the system or himself. He doesn’t have to. He’s a better writer than that.

Or, even more to the point, “Shooting An Elephant.” [Yes, another free read.] Here Orwell is a policeman in Burma. An elephant has gone mad and is ravaging the bazaar. Orwell — who hates his job, the imperialism it serves and, for good measure, “the natives”— calls for his rifle. He doesn’t want to shoot the elephant. He knows: “When the white man turns tyrant, it is his own freedom he destroys.”

But now the elephant kills a man. Half measures? Not possible. Three shots take him down. More follow. But it is hard to kill an elephant; Orwell needs another gun and more bullets. How does it end?

The owner was furious, but he was only an Indian and could do nothing. Besides, legally I had done the right thing, for a mad elephant has to be killed, like a mad dog, if its owner fails to control it. Among the Europeans, opinion was divided. The older men said I was right, the younger men said it was a damn shame to shoot an elephant for killing a coolie, because an elephant was worth more than any damn coolie. And afterwards I was very glad that the coolie had been killed; it put me legally in the right and it gave me a sufficient pretext for shooting the elephant. I often wondered whether any of the others grasped that I had done it solely to avoid looking a fool.

In essay after essay — skip most of the fiction; he’s no master — Orwell writes clean, satisfying prose, what he liked to think of as “prose like a windowpane.” These essays mattered then. If you can connect some dots, you’ll see they matter now.

What I especially cherish is Orwell’s integrity. We hear that word used wantonly now. When it’s applied to newscasters and public intellectuals and writers who wouldn’t know what to think if their puppeteers stopped pulling the strings, it’s blasphemy. Here is a passage I love: Orwell writing about the integrity of Charles Dickens — and, if you will, about himself:

When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. I feel this very strongly with Swift, with Defoe, with Fielding, Stendhal, Thackeray, Flaubert, though in several cases I do not know what these people looked like and do not want to know. What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens’s photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high color. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry — in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.

Orwell would have something to say about the smelly little orthodoxies now contending for our souls.

BONUS VIDEO