Books |

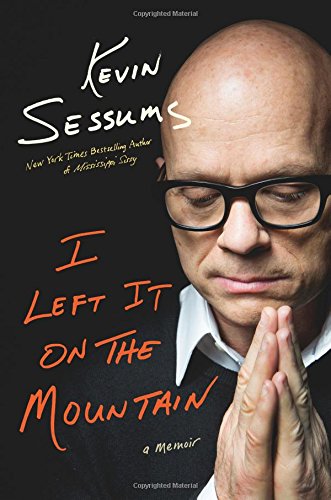

I Left It On the Mountain

Kevin Sessums

By

Published: Feb 24, 2015

Category:

Memoir

Kevin Sessums is gay. He’s HIV positive. He was a crystal meth addict. He now lives in San Francisco and edits FourTwoNine, a magazine that celebrates the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and ally (LGBTA) community. If you follow him on Facebook, you know all of this because you are reading his journal, posted several times a day.

Kevin Sessums is the king of oversharing. On Facebook and in his longer lasting books, he spares the reader nothing. From the New York Times review of Mississippi Sissy, his first memoir:

He was orphaned before the age of 10. Father, car wreck, one year. Mother, cancer, the next. He was repeatedly molested, twice by a predatory minister and once in a movie house restroom, where he was nearly choked to death by his attacker. As a teenager, he discovered the bludgeoned body of his dearest friend, mentor, role model and housemate, a newspaper editor and local literatus named Frank Hains, who had been ritually gay-bashed and murdered in their home just minutes before.

Can’t get worse? In “I Left It on the Mountain,” it does, much, much worse, and if you have a delicate constitution, you might do well to leave us here and come back another day. I was tempted to, several times. But the former addict has, in his writing, the power to addict the reader. And there’s the fact of his survival: Kevin Sessums fought for his life, and although sobriety and sanity must be newly affirmed every day, for now it looks as if he won, and won big.

The book begins in 1990, with Sessums interviewing Madonna — who else?— for Vanity Fair. [Disclosure: We were briefly colleagues at Vanity Fair.] They talked about the early deaths of parents. That made it his definition of a good interview: “a conversation performed as a private one.” And then it’s on to the Oscar party, and so much starfucking it’s dizzying. Here’s an excerpt. See what I mean? Sessums leads you past the velvet rope into the rooms where bold-faced names reveal themselves. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

A happy man? Not nearly. And soon he’s taking us back to his childhood, and his mother’s hospital room: “I was tempted to pull the needle out of her arm and stick it into me so I too could feel that instant calm.” Will it surprise you, decades later, he learns he’s HIV positive? That he uses needles to inject drugs? Or that, a few pages later, he’s describing a meth-fueled sexual encounter with a level of detail that would not make a Republican politician feel warmly about homosexuals?

It’s a dizzying account. At a tender age, he trades Mississippi for Manhattan, meets famous writers and social figures. And ascends. A stint at Andy Warhol’s magazine. And then Vanity Fair, the New York Yankees of the magazine world. What doesn’t he have? Love. A relationship.

In 2009, he makes a pilgrimage to Spain and walks the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. This eats up 60 pages of a 272 page book. It is hugely important to him, much less so for me. I give you permission to skim or skip.

The last section of the book requires — and deserves — your full attention. It starts on July 4, 2010, in Provincetown. Sessums has been hanging out, “smoking meth and fucking around with a few of my drug buddies.” Now, with a sex partner he’s met online, he puts a needle into his arm. “The world sprouted wings and flew away at warp speed.” Seven months of needles follow.

“Addiction, I came to understand, is a proxy battle for the soul.” Sobriety is achieved. And then lost. Four days straight of needles. Lucifer appears. Near-death experiences. Abject grief. Exorcism. Ruin. Eviction. Homelessness.

Heart pounding, I read on. The support of friends. Meetings: 270 in three months. A job paying $100 a week. A 120-square foot apartment. A magazine assignment, and another. And now, a job at a magazine with some of the old Vanity Fair glamour and a lot of the reformed addict’s need for meaning.

“I often say I’ve become the cliché — an old gay man with two small dogs.” In the real world, the orphan’s world of pain, that’s a happy ending.

This book is going to help a lot of people.