Books |

Jules et Jim

Henri-Pierre Roché

By

Published: Apr 23, 2024

Category:

Fiction

SUPPORTING BUTLER: Head Butler no longer gets a commission on your Amazon purchases. So the only way you can contribute to Head Butler’s bottom line is to become a patron of this site, and automatically donate any amount you please — starting with $1 — each month. The service that enables this is Patreon, and to go there, just click here. Thank you.

—

Paris in the Spring. Well, perhaps not this year, with the prices jacked up for the Olympics. Maybe this Paris: A Half Hour from Paris: 10 Secret Day Trips by Train

Its author, Annabel Simms, is a Brit who moved to Paris and developed a deep knowledge of the fifth arrondissement. Business took her to the modern, soulless inner suburbs. Then an urge “to get into the countryside, any countryside” led her to discover France’s excellent network of commuter trains — and what she was looking for. The 21 daytrips of this book, which has been revised and updated several times, are the happy result.

Or, perhaps, a film. A romance. Two men and a woman. Not exploitative. On Amazon Prime. You don’t even have to leave home….

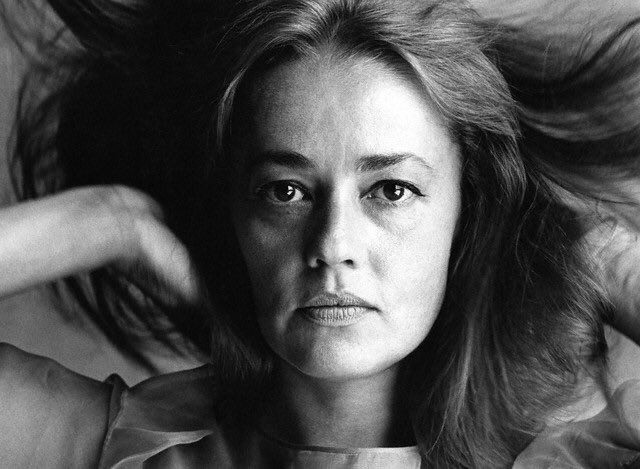

Jeanne Moreau was immortal long before she died. First, for her acting — when Orson Welles called her “the greatest actress in the world,” he spoke for many. And then, as a term of respect, as the first woman to be inducted into France’s Academy of Fine Arts. Her greatest roles were deep in the past, and if you’re not of a certain age or a raging film buff, they’re unfamiliar to you; consider reading the Times obituary and the Sight & Sound appreciation. Or consider the short answer, two films, “Elevator to the Gallows” and “Jules and Jim.”

“Elevator” was a film she shouldn’t have made. Louis Malle was 24, a nobody; she was already Jeanne Moreau. Her agent told her to turn it down. She fired her agent. To read my piece about the film and the Miles Davis soundtrack, click here.

The film that you’ll be asked about on the final exam is “Jules and Jim.” It was a dream collaboration: Moreau and Francois Truffaut. Her part was free-wheeling, liberated, feminist before there was a name for it. The 1962 film pulsed with life. Some critics say it’s Truffaut’s best film; many say it’s one of the best films ever made. [To buy or rent the streaming video, click here.]

What I didn’t know when I saw it: first there was a novel.

The story is compelling. In 1907, Jim, a young French writer, meets Jules, a young Austrian writer. They share everything: “They taught each other their languages; they translated poetry.” Some people assume they’re lovers. But their hobby is women, and in the Paris of the Belle Époque, they collect quite a few. Then they meet Kate, who is of another level of magnitude. Jules marries her. They have two children. But love cools, and there is Jim.

First, though, an all-male love triangle: Henri-Pierre Roché, Francois Truffaut … and me.

Henri-Pierre Roché wrote the novel — his first — when he was 76. He’d spent his life in the avant-garde; he introduced Picasso to Gertrude Stein. His other interest was women. He married twice, but there were many, many more lovers; as Truffaut writes, “He made a work of art out of his love life.” And his novel is more than a little autobiographical. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here.]

Truffaut read the book when he was 23. He fell in love with it; Roché wrote even better than his hero, Jean Cocteau. Short sentences. Everyday speech. The book read like a telegram. Truffaut knew he had to film it, and when he was 29, he did. The style is fluid, exuberant, efficient — Truffaut effortlessly tells a story that spans three decades. No wonder Warren Beatty wanted him to direct “Bonnie and Clyde.”

In 1962, when the film was released, I was 16 years old and new to a boarding school in the suburbs of Boston. My interests, then as now, were writing, music, movies and my social life — that is, girls. On Saturday afternoons, you could find me at the Exeter Street Theatre in Boston, devouring foreign films. Ingmar Bergman was my god. Then I saw “Jules et Jim,” and fell in love both with Truffaut and the way Roché had constructed a story that explained everyone and “blamed” no one.

All these years later, I read the novel. It is astonishing. Not just crisp and fast moving as a thriller, but acute in its wisdom about people, about women, about love. At 240 pages, it spins its wheels only occasionally; mostly, I slowed down to mark passages I wanted to think about later, or steal. Like this:

An early lover took her time over everything she did, so that other people found every moment endowed with the same abundant value as she conferred on it.

Odile was happy all the time. Jim bathed in her blondness at night and the sea by day

Jules no longer slept in the same room as Kate. She treated him kindly but strictly.

Her gospel was that the world was rich and that you could cheat a bit sometimes.

Sex? It perfumes the book. But it is never more explicit than this:

She was in his arms now, sitting on his knees, and her voice was deep. This was their first kiss, and it lasted the rest of the night. They didn’t talk; they let their intimacy take hold of them and bring them closer and closer together. She was revealing herself to him in all her splendour. Towards dawn, they became one. Kate’s expression was full of an incredible jubilation and curiosity. This perfect union, and the archaic smile, more accentuated now — Jim was irresistibly drawn. When he got up to go he was a man in chains.

See why Truffaut memorized long passages of the book, why he used so much of it in his movie? See why this story was ripe to be branded on the psyche of an impressionable boy? See why I think you’ll read it as if it was written — by a master — only yesterday.