Books |

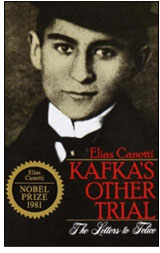

Kafka’s Other Trial: The Letters to Felice

Elias Canetti

By

Published: Jan 25, 2015

Category:

Biography

“Someone must have been telling lies about Josef K. He knew he had done nothing wrong but, one morning, he was arrested.”

So begins The Trial. And with those 22 words, Franz Kafka summarized the nightmare of the 20th century. Gone the presumption of innocence. Hello to the rule of the irrational and dictatorial, tricked up to look legitimate. The State rules. The individual is nothing. And because the disempowerment of the individual happens overnight — in Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis,” Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to find that he has been transformed into a giant bug — there’s nothing to do but submit.

What fuels a story like “The Trial?”

In Kakfa’s case, there are plenty of biographical reasons. But one was largely unreported until 1955, when a packet of letters was sold to his publisher. Only then could we see that Kafka may have been largely motivated to write “The Trial” by the most common of reasons — he’d fallen in love.

Of course there was a twist. As Elias Canetti, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature, explains, love was a torment for Kafka. Especially being loved. That was like being under house arrest. And out of that terrifying loss of freedom, he found both artistic and personal reasons to write “The Trial.”

“Kafka’s Other Trial” is a guided tour of Kafka’s romance with Felice Bauer. It was a romance conducted largely though letters. We have his to her. Hers to him have not survived. But we can easily piece together what they said — Kafka is generally responding, explaining, clarifying.

“I found these letters more gripping and absorbing than any literary work I have read for years,” says Canetti. As would anyone. [To buy the paperback of “Kafka’s Other Trial” from Amazon, click here.]

Felice Bauer met Kafka in 1913. And Kafka’s reaction was strong — just looking at her, he felt “an unshakeable verdict.”

Two days later, he spent ten hours writing a significant story. A week later, another. In the next two months, five chapters of a novel. And then, also quickly, “The Metamorphosis.” As Canetti sees it, the meeting with Felice led to one of the most productive literary periods of Kafka’s life.

And then, a full stop. They broke up. Was it because Felice had praised some other writers? Very possibly. Kakfa felt every wound – even wounds not yet delivered. But he was very attached to the idea of Felice. He agreed to see her again: “He wishes to frighten her away by appearing in person, since his letters have failed to do so.” Something went wrong. In 1914, they became engaged.

A joyous moment? Well, he compared it to the French Revolution; he felt they were bound together for the scaffold. So Felice and a friend sat him down. He felt like a criminal. He felt he was on trial. Of course he was found guilty. And his sentence? In a farewell letter, he speaks of a "speech from the gallows."

And then, having freed himself from Felice, he began to write a novel of an unnamed crime and an assumed guilt. Taken to the extremes in his book, he writes this:

Once more the odious courtesies began, the first handed the knife across K. to the second, who handed it across K. back again to the first. K. now perceived clearly that he was supposed to seize the knife himself, as it traveled from hand to hand above him, and plunge it into his own breast. But he did not do so, he merely turned his head, which was still free to move, and gazed around him. He could not completely rise to the occasion, he could not relieve the officials of all their tasks; the responsibility for this last failure of his lay with him who had not left him the remnant of strength necessary for the deed.

A self-inflicted execution at the end of an engagement? Oh, that’s just the start of what we learn about the last century’s most haunted writer in this 118-page account of a critical year in his life. Open bedroom windows, the importance of sleep, taking a cure — the details are fascinating.

“The work awaiting me is enormous,” Kakfa wrote when he was done with Felice. Seven years later, he was dead. He never resolved his deeply divided views on love and sex. But along with his fiction, he left the letters that Canetti has used to create a riveting mini-biography.