Books |

The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement

Taylor Branch

By

Published: Jan 11, 2017

Category:

Biography

In 1968, Taylor Branch published Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63. I sat down one weekend and didn’t get up until I’d read all 900 pages.

Branch went on to complete a trilogy about King. When he was done, the project had taken 24 years and he’d written 2,306 pages.

I revere King and I stopped after the first volume.

Now? Nobody’s going to read 2,306 pages about King. Even if you believe, as Branch does, that “King’s life is the best and most important metaphor for American history in the watershed postwar years,” you’re not about to read 2,306 pages about him.

So Branch has smartly produced a book that is a primer for millennials, a reminder for adults, and suitable for children. Just 220 pages. In essence, it’s the Greatest Hits of his trilogy — he took 18 of the pivotal events in King’s years as a civil rights leader and cut-and-pasted a few pages from his previous writing on each. And so you’d have context, he provides short prefaces. [To buy the paperback of “The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Branch does not write straight history. He’s telling an epic story, and he goes high in his language. Here’s the conclusion of the assassination chapter:

King walked ahead of [Reverend Billy] Kyles to look over the handrail outside, down on a bustling scene in the parking lot [of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee]. Police undercover agent Marrell McCullough (a mole in the entourage) parked almost directly below, returning with SCLC staff members James Orange and James Bevel from a shopping trip to buy overalls. Orange unfolded his massive frame from McCullough’s little blue Volkswagen, tussling with Bevel, and Andrew Young stepped up to rescue Bevel by shadow-boxing at a distance. King called down benignly from the floor above for Orange to be careful with preachers half his size.

McCullough and Orange walked back to talk with two female college students who pulled in just behind them. Jesse Jackson emerged from the rehearsal room, which reminded King to extend his rapprochement.

“Jesse, I want you to come to dinner with me,” he said. Kyles, overhearing on his way down the balcony stairs, told King not to worry because Jackson already had secured his own invitation.

Abernathy shouted from Room 306 for King to make sure Jackson did not try to bring his whole Breadbasket band, while Chauncey Eskridge was telling Jackson he should upgrade from turtleneck to necktie for dinner.

Jackson called up to King: “Doc, you remember Ben Branch?” He said Breadbasket’s lead saxophonist and song leader was a native of Memphis.

“Oh, yes, he’s my man,” said King. “How are you, Ben?”

Branch waved. King recalled his signature number from Chicago. “Ben, make sure you play ‘Precious Lord, Take My Hand’in the meeting tonight,” he called down. “Play it real pretty.”

“O.K., Doc, I will.”

Solomon Jones, the volunteer chauffeur, called up to bring coats for a chilly night.

There was no reply. Time on the balcony had turned lethal, which left hanging the last words fixed on a gospel song of refuge. King stood still for once, and his sojourn on earth went blank.

Sadness. Infinite sadness. Necessary reading.

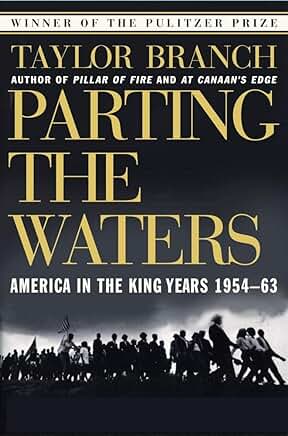

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPH

Martin Luther King Jr. was photographed by Alabama cops following his February 1956 arrest during the Montgomery bus boycott. The mug shot, taken when King was 27, was discovered in July 2004 by a deputy cleaning out a Montgomery County Sheriff’s Department storage room. It is unclear when the notations ‘DEAD’ and ‘4-4-68’ were written on the picture.