Books |

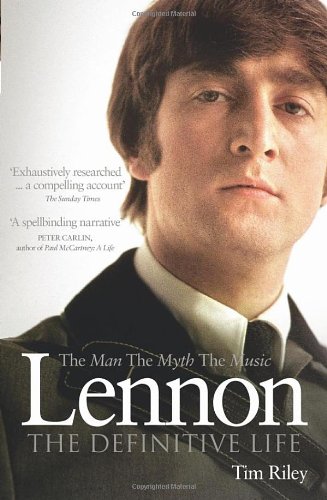

Lennon: The Man, the Myth, the Music, The Definitive Life

Tim Riley

By

Published: May 20, 2014

Category:

Biography

Guest Butler Joe DePreta, a New York marketing consultant and writer on cultural trends, is a student of musicology from Sinatra to the Sex Pistols.

When I was a kid, my friends and I sat on a park bench and debated and talked over each other like a Robert Altman ensemble about the important hierarchies of the musical meritocracy. Beach Boys vs. Four Seasons. Hendrix vs. Clapton. To a handful of vociferous fifth graders the wining point of view was acutely important, and musical factoids were more relevant than Shakespeare or the Yankees. To convert someone by your rationale was better than a trophy. Album covers and liner notes were biblical.

Those debates — arguments, really — served as our summer camp.

And there was no debate more passionate than this: Lennon vs. McCartney.

This began as a Beatles versus Rolling Stones conundrum. Though we couldn’t articulate it at the time, we knew the Stones were a great rock band that played excellent pop, and the Beatles were a great pop band that rocked.

Lennon versus McCartney was more complex and esoteric, layered with cultural imperatives and moral underpinnings. Paul stood at the microphone, played to the camera, flirting with the audience at the right lyrical moment. John, though blessed with one of the greatest voices in the history of blue-eyed soul, seemed Dionysian. Rock and Roll was now about issues bigger than cars and boy-loves-girl. Bye-bye “Surfer Girl,” hello “A Day in the Life.”

America in general, and New York in particular, embraced John Lennon as its own heroic and martyred Beatle: prolific, passionate misogynist turned Dakota-dwelling househusband; Harry Nilsson’s LA partner in debauchery turned repentant little boy; radical philanthropist turned talk show iconoclast.

In his seminal “Lennon: The Man, the Myth, the Music – The Definitive Life,” Tim Riley, NPR music critic and professor of Journalism at Emerson College, painstakingly examines Lennon from his days as an abandoned child in Blackpool through the iconic album sessions, ultimately leading to the Dakota years and John’s assassination (Riley refuses to refer to Mark Chapman by name, an honorable if not artistic decision). While the book reveals an abundance of compelling anecdotes that give the reader a fresh prism through which to understand the man, the reward is a firmer grasp on what drove, and changed, the music.

The book not only manifests the life and music of Lennon, it connects the dots of the talent, the psychology and spiritual quests. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

At 661 pages, the book covers illuminating new ground. The magnitude is so rich that I tracked down Riley so we could create a more erudite park bench session. He graciously agreed.

JDP: What was the impetus to tackle such an exhaustive examination of John Lennon?

TR: Peter Guralnick’s two-volume Elvis Presley biography made an enormous impression on me, and I wanted to do the same approach with Lennon. Most of the Lennon narratives deal with surface aspects of his life: his public behavior, his drug intake, and his celebrity status. In my view, his primary identification has always been as a MUSICIAN, and I wanted to explore that angle: tell the story of rock’n’roll through his ears, and how his life influenced both his writing and singing style.

JDP: Albert Goldman’s biography of Lennon, which preceded yours by 23 years, was very scandal-focused. Did that catalyze your need for a fairer exploration?

TR: You’re way too kind to Goldman, whose book projects a scary degree of self-hatred. Because he remained the only American writer to pen a large-scale bio, it seemed time to answer his screed with something more sympathetic.

JDP: One of the common threads of your book is Lennon’s sense of irony. Did he see the irony of the Beatles rendering obsolete the very roots rockers he idolized?

TR: Very much so. As early as 1963 he told Michael Braun, “This isn’t fame, it’s something else.” He seemed astutely conscious of how much larger than life the Beatles became and how that status could work both for and against them.

JDP: You dispel the long held myth that the Beatles were the well-scrubbed middle class boys and the Rolling Stones were the bad boys from the wrong side of the tracks. Was that just spin from guys like Brian Epstein and Andrew Loog Oldham?

TR: In broad terms yes, but the larger theme complicates this: how the Beatles were perceived at the time versus how history has reframed them. They were indisputably Gods of their realm, but history has since buffered them from any of the mundane tabloid crap they endured. So this becomes another irony: history deifies them further with Lennon’s death.

JDP: Early in the book, while relating a story about the possibly bogus inspiration for Lennon’s “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” you wrote: “Lennon was more confessional than the most melodramatic singer-songwriters he inspired; (and that) he recounted lapses of morality and taste” to strangers rather than intimates. Was that ability to confess on vinyl the core of his lyrical appeal?

TR: Fascinating contradiction of his character: he avoided conflict pathologically, yet still felt driven by a severe moral scrupulosity, much of it conscious. He’d rather tear into Paul in song than in person.

JDP: Lennon’s confessional poetry seems to be rooted in an ongoing Freudian need. Is that what made Yoko Ono so powerful? You intimate that Yoko was catalytic in the Beatles’ breakup.

TR: Tricky to even call her a catalyst, I tried to put the onus on Lennon, since she could never have held any power whatsoever had he not granted it to her. His behavior in this period really redefines passive-aggressive. He wanted out of the Beatles, so he used her as a crowbar to divert the flack away from himself.

JDP: In keeping with that theme, you also trace the arc of John’s abandonment by his biological parents, handed over to his mother’s sister Mimi who raised him, and why a lover was never as satisfying as the omnipresent control of Ono.

TR: Yeah, and the dime-store psychology remains irresistible even though it’s a crude simplicity compared to what such an inner life must have felt like. Think on his childhood abandonment and then listen to “Strawberry Fields Forever” and all the psychobabble just evaporates.

JDP: History shows that no band has influenced music as holistically as the Beatles. One of the questions for the ages is: after they broke up, what the hell happened? Other than Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album and Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, the solo work was rather confectionary.

TR: It demonstrates how dependent on one another they were, how far those ensemble bonds flowed from performing to writing, and how they never found the same intimacy with any others. Sometimes the independence you earn in your musical career turns out to be what your material needs least.

JDP: Just for fun, who’s the better lead singer, John or Paul?

TR: I hate to choose. I adore ALL of John’s singing, I even defend his ROCK’N’ROLL album, even though he’s obviously slumming. On the other hand, you can’t say McCartney is any less interesting or compelling on many tracks, and of course their duets still gives the spine tingles.

JDP: “Imagine,” to the chagrin of many rock critics, has taken on a life of its own as a global anthem. In the book you refer to it as “Lennon’s most misinterpreted song.” Why?

TR: It’s heard as a giant pop greeting card for all mankind, but it’s really an argument for agnosticism, abolishing religion and capitalism (“imagine no possessions”), which even Communists might consider radical. OF course he doesn’t really MEAN it, he’s just SUGGESTING we put aside our illusions of what divides us and consider what we share in common. You have to take the literal side of this seriously: it’s such a pure Utopian ideal it’s laughable. And he sings it with such directness you’d swear he wants us to swallow it whole. It hasn’t worn very well, it sounds like a period piece, a pure product of 1960s fabulism that, in 1971, tried to reboot an era instead of extend it into a new political realism. It makes “All You Need Is Love” sound wise. I prefer “Instant Karma,” even the torrential ambivalence of “Revolution.”

Looking back on those halcyon bench days, we’d never have imagined the public’s unquenchable thirst for the Beatles. Riley’s book now enlightens us why the band and John remain evergreen.