Music |

Leonard Cohen (1934-2016)

By

Published: Nov 07, 2017

Category:

Rock

November 7, 2016. Leonard Cohen fell in the night and died. A year later,, when I mentioned the anniversary, friends said the same thing: “It can’t be a year.” I understood. It felt at once forever ago and just this minute. Ancient and fresh. Tender and raw.

When he died, I almost had to smile at his timing: the day before the election. I wasn’t surprised to see the t-shirt: Trump killed Leonard Cohen. And a song: “God, I’ll Trade You Donald Trump for Leonard Cohen.” Or to understand why, weeks before his death, he gave generously of his time to David Remnick for a magnificent profile in The New Yorker.

As someone who understands that we are a culture of scorecards and hierarchies, the obvious thing to say is that Cohen’s music is, with Dylan’s, the most significant North American catalogue of the last half-century. For those who have never heard his songs or have no tolerance for him, ignorance and dismissal are understandable — but wrong. Cohen’s range as a composer was narrow; as he noted, “People said I knew three chords when I knew five.” His vocal range was even more limited. A fan got it exactly right when he said, “No one can sing a Leonard Cohen song the way Leonard Cohen can’t.” The dirge-like songs and midnight voice made him an easy target for reviewers. “The poet laureate of pessimism.” “The grocer of despair.” “The godfather of gloom.” “The prince of bummers.” And, inevitably, “music to slit your wrists to.” [Although I generally oppose anthologies, I suggest “The Essential Leonard Cohen.” It’s two-and-a-half hours of music. 31 songs. Only fanatics like me could want more. [To buy the CD of “The Essential Leonard Cohen” from Amazon, click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

For those of us in the Cohen cult, Leonard Cohen was much more than a musician — he was our intimate stranger, the poet laureate of our secret lives, our personal bard. The subject of almost all of his songs is love, or, more correctly, the “war between the man and the woman” that may take the form of an incurable disease we call love. Someone said, “You play Leonard after the lovers have left and are in the arms of others.” Not always. Sometimes the women were there, and so was a kind of distress you didn’t understand and didn’t particularly want but couldn’t resist — like a black-and-blue mark you can’t help pressing, I used to think. There was something about that pain…

A famous story: In l967, 32-year-old Leonard Cohen — a novelist and poet just starting out as a singer/songwriter — walked onstage at Carnegie Hall, looked out at the audience, and started shaking. “I can’t do this,” he said, and left the stage. In the wings, Judy Collins took his hand, led him in front of the audience again and sang “Suzanne” with him.

Another story, just three years later: 35-year-old Leonard Cohen agreed to perform at England’s Isle of Wight music festival. It was not a happy event. Angered that there was a wall to keep out those who hadn’t paid, some of the young festivalgoers rebelled. They tore down fences. They crashed the gates. There were fires and fights. There was garbage. 600,000 people. Living outside. For almost five days.

At 2 in the morning of the fifth and final day, Leonard Cohen was awakened and asked to hurry onstage. There was no piano, no organ. Cohen, in his pajamas, insisted on both. And then he went back to his trailer to get dressed.

At 4 in the morning, Cohen took the stage. He looked into the darkness and, gently, slowly, told a story of going to the circus as a kid and liking only the moment when the audience lit matches in the darkness. He asked the crowd to light matches, and he waited while they did, and then he sang “Bird on a Wire,” and they listened to him as if he were a prophet.

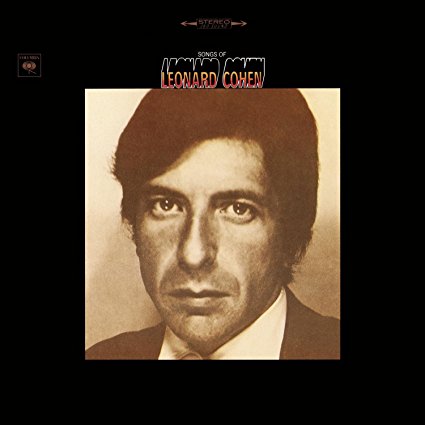

What transformed him in those three years? His first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen. And knowing that his songs would be the soundtrack of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Robert Altman’s anti-Western:

He joked about his record company: “I was always touched by the modesty of their interest.” But he didn’t need promotion — his songs found a way. “Hallelujah” was buried in one of his least popular albums. It’s gone on to be recorded by more than 60 singers. The video’s been watched hundreds of millions of times.

I can’t choose my favorite videos. There are too many, and I can go for years without seeking them out. But like pretty much everyone, I was knocked out by “You Want It Darker” — a farewell letter from a man who knew death was about to knock on his door. “I’m ready, my Lord,” he sang. And the rabbi intoned a prayer. [To buy the CD of “You Want It Darker,”, click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

More Cohen? You might go on to the novel I like: The Favorite Game. And one I like less: Beautiful Losers. And some CDs: Practical Problems and Old Ideas and a flawless live album.

In all of this music, a few emotions repeat: sadness, loss, ironic wit. In his songs, the dice are loaded, the good guys lose, the lover leaves.

But this is just observed reality for Cohen, not cause for despair. And so we ultimately cherish him for a clear-eyed acceptance of reality that we tend to resist in our own lives — for his courage. “I’ve come to the conclusion, reluctantly, that I am going to die,” he told an interviewer. What followed was pure Cohen: “But, you know, I’d like to do it with a beat.”

—

To read Leonard Cohen’s only online chat, conducted shortly after 9/11, click here.