Books |

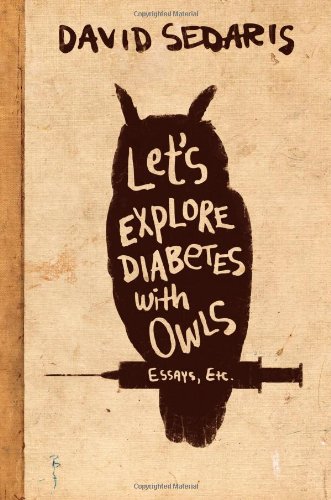

Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls

David Sedaris

By

Published: Apr 28, 2013

Category:

Memoir

David Sedaris launched his career by reading a seriously funny story on NPR about working as a Christmas elf at Macys. Overnight, he became our humorist laureate, serving up personal history that is as ironic as our cultural reality. Now he’s a star on the lecture circuit.

Sedaris fans blindly love every word he writes. Over the years, I’ve morphed into only an occasional fan. Because Sedaris has a problem: success. It’s a trick to get people to care about your personal quirks and difficulties when you’ve sold more than 7 million books and own more than half a dozen residences on two continents. That this book is as good as it is is a considerable triumph. (To buy the hardcover edition of “Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.)

Start with the flaws: “Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls,” at 275 pages, is padded with six pieces that are new for Sedaris. "Over the years I’ve met quite a few teenagers who participate in what is called ‘Forensics,’" he writes. "Students take published short stories and essays, edit them down to a predetermined length, and recite them competitively. To that end, I have written six brief monologues that young people might deliver before a panel of judges. I believe these stories should be self-evident. They’re the pieces in which I am a woman, a father, and a sixteen-year-old girl with a fake British accent."

Sounds good? They’re easy targets. A critic has said: “They drip with contempt for the kind of teapartying middle American who loves guns and hates gay marriage.”

Bitterness and contempt may be new tones for Sedaris, but that’s understandable — and, in other pieces, welcome. In “Dentists Without Borders,” the book’s lead-off essay, he chronicles his experiences with dentists in France. They are cheap, kind, efficient, charming in their way. But they’re not American, so, really, how they can be any good? The answer is the last paragraph:

I’ve gone from avoiding dentists and perodontists to practically stalking them, not in some quest for a Hollywood smile but because I enjoy their company. I’m happy in their waiting rooms, the coffee tables heaped with Gala and Madame Figaro. I like their mumbled French, spoken from behind Tyvek masks. None of them ever call me David, no matter how often I invite them to. Rather, I’m Monsieur Sedaris, not my father but the smaller, Continental model. Monsieur Sedaris with the four lower implants. Monsieur Sedaris with the good-time teeth, sweating so fiercely he leaves the office two kilos lighter. That’s me, pointing to the bathroom and asking the receptionist if I may use the sandbox, me traipsing down the stairs in a fresh set of clothes, my smile bittersweet and drearied with blood, counting the days until I can come back and return myself to this curious, socialized care.

There is a horrific story called “Memory Laps,” about the summer of his tenth year, when Sedaris swam in competition at a country club in Raleigh, North Carolina. It’s not really about swimming — the real subject is his absolute shit of a father, who not only never praised him but had no trouble identifying and praising other males he believed were much more talented and praiseworthy. By story’s end, I wanted to bitch slap Dad. But in a recent interview, Sedaris has a different view:

I would never want anyone to think that I would have wanted a different father. I always acted against my father, right? And [‘You’re a big fat zero’] was really, that was his mantra when I was growing up. You know, ‘What you are is a big fat zero,’ but it’s what got me out of bed every morning, thinking, ‘Well, I’ll show him.’ And I don’t know if my dad knew that. I don’t know if it was part of his master plan, but it really worked. You know, my mom was a cheerful, supportive person, and so I didn’t really need two parents like that. One was enough.

It’s tempting to read a number of these stories as blasts against irrational male authority figures. But worry not, Sedaris lovers, there’s plenty of What You Came For. A piece about a trip to Hawaii — Sedaris is rich beyond rich now, he takes trips, a lot of trips, and because his writing is a kind of diary, you go around the world with him — begins with the lei you get when you step off the plane: “an Olympic medal for sitting on your ass.” Then it goes somewhere else, ending with a meditation on sea turtles. Gorgeous stuff.

A piece on flight delays gets to political outrage, but not before a stop at cultural observation:

I should be used to the way Americans dress when travelling, yet still it manages to amaze me. It’s as if the person next to you had been washing shoe polish off a pig, then suddenly threw down his sponge, saying, ‘Fuck this. I’m going to Los Angeles!’

“#2 to Go,” about spitting and bathroom habits in China, is a scream. Vulgar? Yes. That’s the foundation of the humor. The theft of a laptop. Picking up trash. It’s all grist. As ever, great lines abound: “He was right on the edge, a screw-top bottle of wine the day before it turns to vinegar.”

But it’s the personal edginess that makes the book for me. “A Happy Place” is about his colonoscopy. He’s encouraged, as he goes under, to go there. Where he does go — let’s just say Dad gets his. Not, if that happened, that Dad cared.

The title? It emerged, in bits and pieces, at a book signing, when he was searching for a clever inscription:

This woman wanted me to write to her daughter: ‘Explore your possibilities.’ And I said, well, I’ll keep the word explore. And then I wrote: let’s explore diabetes – then I thought I’m not done yet – with owls. And then I thought: That’s the title of my book.

Anything else you want to know? Go to the book.