Books |

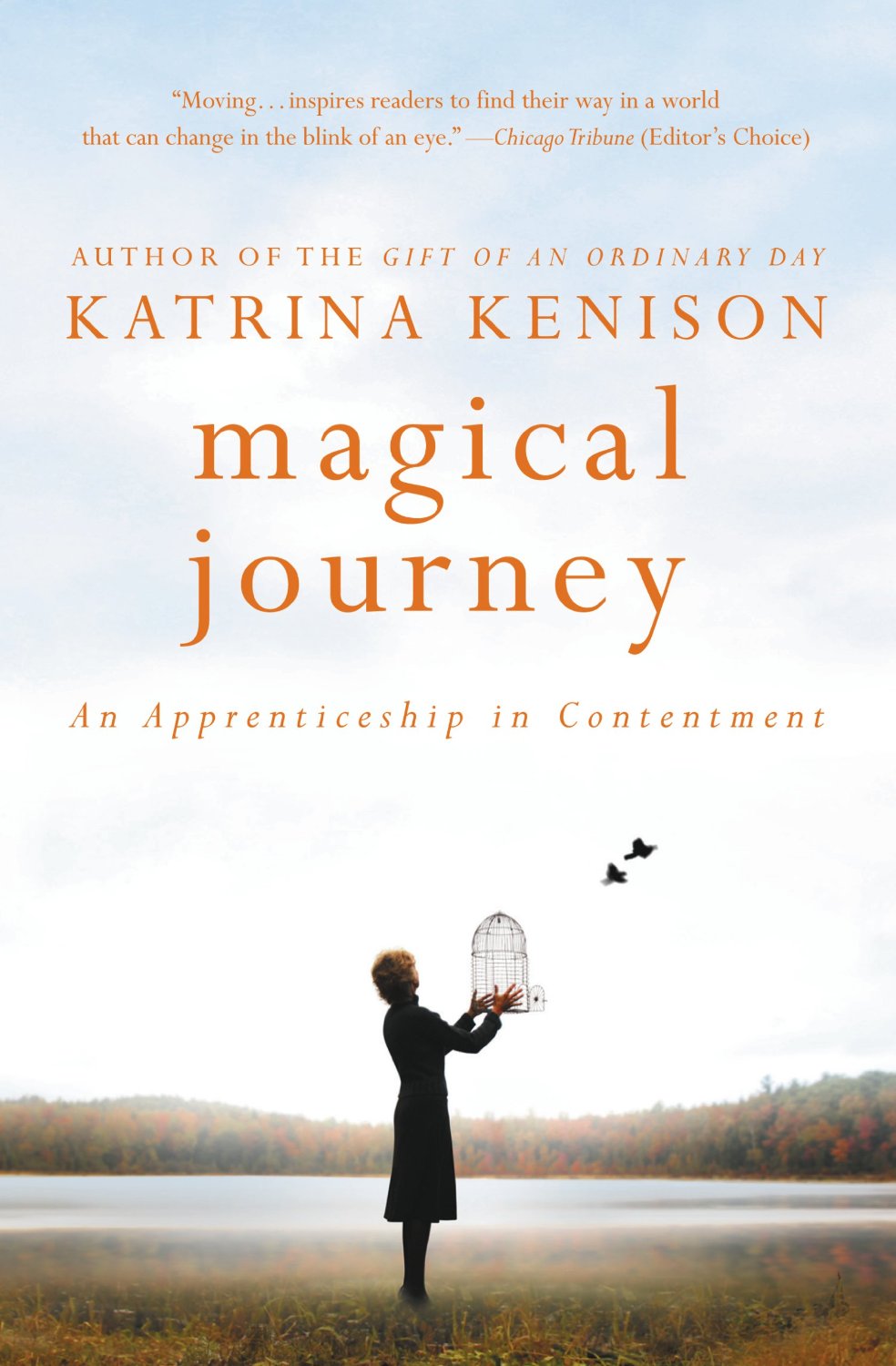

Magical Journey: An Apprenticeship in Contentment

Katrina Kenison

By

Published: Mar 23, 2016

Category:

Memoir

Katrina Kenison is a writer with a following. That she was previously unknown to me is a function of the kind of writer she is and the kind of following she has. She writes memoirs, largely about her personal development as a wife and mother and sentient being trying her best to “celebrate the gift of each ordinary day.” Her readers, I glean from her blog, are like her: women of a certain age, grappling with First World problems.

If you peg her as Thich Nhat Hanh for suburban white women, Joseph Campbell for the masses — that wouldn’t be a bad first take.

It would also be wrong.

“Magical Journey” begins with Kenison driving her younger son to boarding school. This is a good thing — he needs to go. But motherhood has been the biggest part of her life: “Being with my children, watching them grow and change and meet the world, deepened my own relationship with the world.” And now? “My life as a mother of children at home is over.”

More change awaits. Marie, one of her best friends, died recently; grief feels like amputation. Her marriage, though solid, is at the quarter-century mark. And there’s the not small matter of her own mortality: “Going down turns out to be harder than climbing up… I’m not at all certain of the path.” [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

What happens in these pages? You could say: not a lot. She takes a month-long yoga course at Kripalu. Goes to her 30th college reunion. Spends a few days with a friend in a cabin in Maine. Learns Reiki. Walks 26 miles with friends to raise money for cancer research in Marie’s name.

Not a lot, that is, on the outside. Inside there’s a revolution. A coming to terms — acceptance, and its sisters, compassion and love. Re-learning what Marie knew, right to the end: “There is so much goodness in the world.” Really being with others, and not just in the big operatic moments, but as they live out “simple stories of ordinary struggles.”

This is not easy work. Now that I hear the clock ticking, I’ve also taken it on. If you are of a certain age, you have too. Or will. It’s a bitch, isn’t it? Maybe even harder than writing a book or stopping a war or protecting the rights of women. Which makes a book like this — a book by a writer who, like us, has a First World life and issues — possibly useful.

At Kripalu, Kenison is asked to write a letter to herself. It will, she’s told, be sent to her “at the right time.” It arrives, as it should, at the end of the book, when Kenison has almost forgotten about it. In a video, she reads what she wrote to herself:

Is that appalling, or what? Treacle, every last word, especially “journey.” But — how annoying is this? — treacle that feels like truth, treacle that is, annoyingly, true. How humbling is that?

I loathe books where women sit in their comfortable houses, make tea, chat with friends. I loved this one.