Music |

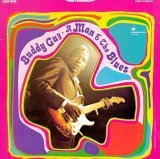

Buddy Guy: A Man and the Blues

By

Published: Oct 09, 2016

Category:

Blues

Eric Clapton called him the "greatest blues guitarist ever."

On his first trip to England, Rod Stewart volunteered to be his valet.

Jimi Hendrix said of him, “Heaven is lying at his feet while listening to him play guitar.”

The musician that these giants raved about — and women adored — is less famous than he ought to be. Second-rate talents with decent marketing and a bit of luck are famous, at least for a while — if Buddy Guy is among the greats, why can’t we name any of his hits?

In part, because Buddy Guy is the king of Chicago blues, a genre at once rough and tender, down-home and ultra-knowing, and, at its core, black as the skin of the darkest field hand in Mississippi — and thus not of interest to the mass audience until some skinny white guy is stroking that Fender six-string Stratocaster.

And, in part, because Guy and his producers botched his career. He came to Chicago from Louisiana: "I was so far out in the country, man. We didn’t have running water, no electric lights, no radio, and I didn’t know nothing about no electric guitar. We used to get the catalogs, like from Sears, and that’s how our mother would order our clothes. Didn’t have no stores there to buy clothes from."

He started playing professionally in Baton Rouge, won a contest, headed north. In the early 1960s, when some of the best Chicago blues records were made, he was a session guitarist; anything fancy he played was mixed down.

By the mid-l960s, Buddy Guy was Jimi Hendrix before there was a Hendrix; he would pick the guitar with his teeth and play it over his head. (One night Hendrix came, stood in the front row and taped Guy’s performance so he could go to school on it.) At the same time, Buddy Guy was Clapton before there was a Clapton. In fact, the young British bluesman got the idea for Cream as a power trio from Buddy Guy. And as for Cream’s music, well…. "You know that Cream tune, ‘Strange Brew’?" Guy has recalled. "Eric and I were having a drink one day, and I said, ‘Man, that Strange Brew… you just cracked me up with that note.’ And he said ‘You should…’cause it’s your licks.’"

By the time anyone in Chicago understood or appreciated what Buddy Guy was playing, others had patented that sound. He made a few authentic Chicago records, then languished without a record contract for a decade. By the time of his third or fourth rediscovery, he was old enough to be a grandfather — and by then, he had moved beyond pure blues to a kind of showmanship that upstaged the music.

But there was a window — a few years in the mid-l960s — when Buddy Guy had it all: a powerful set of songs, masterful compatriots, a willing record label. You can hear him in those glory days as the wingman for Junior Wells in that harmonica player’s electrifying and flawless Hoodoo Man Blues. (For contractual reasons, he’s billed on early editions of that record as "Friendly Chap.") And then, in 1968, he made a debut record that is nothing less than a primer of Chicago blues. [To buy the CD of "A Man and the Blues from Amazon and get a free MP3 download, click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

On "A Man and the Blues," the music has been mixed so Buddy Guy is front and center, and he is never less than dazzling. He plays a single note and lets it hang until it drops out of hearing range. Or he’ll rain notes down like bullets, a staccato assault on your ears. But he never plays anything just for show — everything is in the service of the song. And he’s backed by great musicians, especially Fred Below on drums and Otis Spann on piano. Here’s a challenge: On slower songs, tune everyone else out and listen to what Spann and Below are playing. It may be blues, but it’s as least as subtle as jazz.

There are fast songs that get toes tapping and the heart pumping, especially the Motown hit "Money (That’s What I Want)" and "Mary Had a Little Lamb." But it’s the slow stuff that takes your breath away. "What can a man do/when the blues keep following him around?" he asks. "So many ways you can get the blues," he moans. He’s sitting "a million miles from nowhere" in a shack by the cotton fields. But he’s a man. And so he looks for a man’s solution: "I’m gonna find me some kind of good woman/Even if she’s dumb, deaf, crippled or blind."

It’s lonely, lonely stuff — it’s the very definition of the blues. "Give me a little piano now, Spann," he cries, and in comes a glissando as delicate as Chopin and twice as heartbreaking. Makes you want to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey, even if you don’t smoke or drink.

Don’t feel sorry for Buddy Guy — over the years, he’s sold millions of records, won Grammys, achieved the status of a legend. One of the last, in fact; he’s the sole survivor of the Chicago greats. No, the sorrow is for us; "A Man and the Blues" should have spawned a half dozen albums that would have given us a catalogue as rich as that of John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters.

Before he left home, Buddy Guy’s father told him, "Son, don’t be the best in town. Just be the best until the best come around." But no one I can think of has ever come around with anything better than "A Man and the Blues."