Books |

My Name Is Lucy Barton

Elizabeth Strout

By

Published: Feb 02, 2020

Category:

Fiction

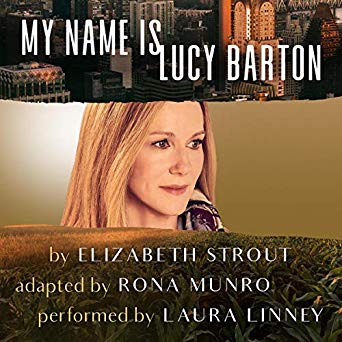

Laura Linney is doing “Lucy Barton” as a one-woman show in New York. It’s a limited run, ending February 29. The New York Times was giddy with praise: “We’re grateful for the alchemical, unquantifiable mix of factors that allows this woman — embodied by this actress, at this moment, in this place — to share with us so raptly what she knows, or even thinks she knows. When Lucy says, with a satisfaction that’s bigger than happiness, that “all life amazes me,” we feel exactly what she means.” Tickets? I found none through the box office. Which means you need to go to Stubhub — but look at those prices!

But wait — you can see “My Name Is Lucy Barton.” Laura Linney has recorded the play. There wasn’t much staging in the theater; her performance is all in her voice. And you can thus “see” it at home, for hundreds of dollars less than the cheapest theater ticket. [To buy the audiobook from Amazon, click here.]

—–

The best fiction I read in 2016? Elizabeth Strout’s “My Name Is Lucy Barton.”

It had everything I like in a novel. Topic sentences, one after another. A first person narrative. Short chapters. Effortless time shifts that don’t feel like flashbacks. Characters pinioned by emotions they have trouble articulating. 191 pages.

To tell you much about the plot is pointless. The story can’t be separated from the writing. The way Lucy tells the story of the nine weeks she spent in a Manhattan hospital “many years ago” turns her bedridden, passive time there into something more urgent. Ann Patchett: “I believed in the voice so completely I forgot I was reading a story. I felt like I was being pulled aside by a friend who was saying, ‘Look, there’s something I have to tell you.’” [To read the beginning of Chapter 1, click here. To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. And now: To buy the Laura Linney audiobook from Amazon, click here]

But, okay, the story: Three weeks into her hospitalization, Lucy looks up to see her mother sitting in a chair at the foot of her bed. It’s a stunning surprise — her mother’s never taken a plane. But Lucy’s husband has asked her to come, and there she is, an intensely private woman suddenly turned into a companion and confidante.

Her mother’s arrival is uplifting for Lucy: “Her being there, using my pet name, which I had not heard in ages, made me feel warm and liquid-filled, as though all my tension had been a solid thing and now was not… That night I slept without waking, and in the morning my mother was sitting where she had been the day before.”

What do they talk about? Not themselves — when Lucy tells her mother she’s had two stories published, her mother looks at her “quickly and quizzically, as if I had said I had grown extra toes, then she looked out the window and said nothing.” Their subjects are other people. Girls Lucy went to school with, and what happened to them. Neighbors. Teachers. Lucy’s brother. It is through these stories that we learn what Lucy’s childhood was like: so dirt poor that her family lived in a garage, isolated from their neighbors.

This is a success story. Lucy is a published writer, and one of her novels — the story she tells here, if I have that right — brings her recognition and money. But there is a sadness at the core of the book, and it’s that sadness that had me, more than once, putting my hand to my mouth and saying oh no. Again, this is the power of Strout’s style — she writes in short, declarative sentences that, without inflection, lay out the facts. Not murder and mayhem, but the stuff of own lives: what was done to us, what we did to others, how even happy memories have the power to hurt us.

Disguised memoir? No. And yes, a bit. Elizabeth Strout’s parents were professors, but “we lived deep in the woods of New Hampshire, and also Maine… There was no television in our house and no newspaper… By the time I went to college, I had seen two movies: ‘101 Dalmatians’ and ‘The Miracle Worker.’ My brother and I did not go to parties, and we did not date, or hang out, or talk much on the phone the way other adolescents did.”

It’s clear in every sentence: Elizabeth Strout knows this story in a way that makes Lucy Barton’s life not just credible, but real. Which is why, when you get to the remarkable last sentence — it’s just four words — if you’re at all like me, you’ll have to sit for a moment, because you and the character and the story have merged in a way that takes you to a place and a feeling you know but rarely acknowledge.