Books |

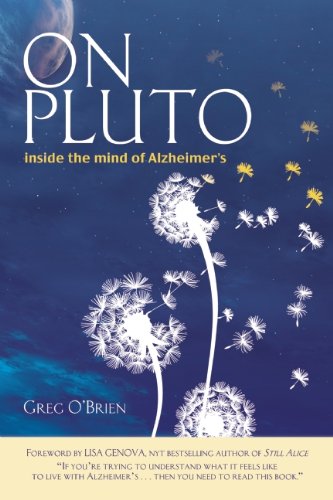

On Pluto, Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s

Greg O’Brien

By

Published: Mar 18, 2015

Category:

Health and Fitness

Guest Blogger Gerald Secor Couzens,the author of more than two dozen health books, is the managing editor of The Scientific American Memory Disorders Bulletin, a 45-page print quarterly for people interested in memory problems, Alzheimer’s in particular.

——–

Greg O’Brien had a front-row seat witnessing the destruction that Alzheimer’s disease can wreak on a loved one. For years, he had watched as his maternal grandfather and, later, his beloved mother suffered before eventually succumbing to the brain-robbing disease that has no cure. It was soon after, in 2009, that O’Brien, a longtime reporter, newspaperman and writer from Brewster, Massachusetts, was diagnosed with the early-onset variant of Alzheimer’s disease. He was 59 years old, with a job he liked and a wife and three children he loved.

The dementia diagnosis, horrific as it was, did not come as a complete surprise to O’Brien — he’d been experiencing worrisome symptoms that he’d guarded for years. “I was having difficulty recognizing familiar places and people,” he says. “I also had the beginnings of poor judgment and rage.”

While Alzheimer’s most commonly affects older adults in their 80s, it can also appear in people in their 30s and 40s. When the disease occurs in someone under the age of 65, it is known as younger- or early-onset Alzheimer’s. About 5 percent of the 5 million or so Americans who now have Alzheimer’s have the early-onset variety. Like O’Brien, many had careers and families when they had their death sentences handed down. Diagnosis to death can be a matter of years; some people live a decade or more.

Younger-onset Alzheimer’s can be hard to diagnose at its beginnings, as it is often mistaken for difficulty adjusting to changing life circumstances, such as children leaving home, loss of employment, or a “mid-life” crisis.” Early symptoms can include forgetting important things, particularly newly learned information or important dates, repeatedly asking for the same information, losing track of where you are and how you got there, and difficulty joining conversations or finding the right word.

When O’Brien’s doctor eventually told him that he had Alzheimer’s, his first instinct as a journalist wasn’t to feel sorry for himself, but to report. “To fight an enemy, you have to know the enemy,” he says. “I began to research so I could eventually write a book about my Alzheimer’s battle. I met with experts and learned all I could. Here was a new, challenging topic to take on. Unfortunately, I knew the ending of my book before I started writing it.”

O’Brien’s memoir, On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s, is an intimate look at his life, past and present. It’s a beautifully painted story, both a poignant and distressing tale, that he raced to finish while his brain synapses still transmitted thoughts and relayed memories. The mighty struggle to compose his sentences, working off written notes scattered about his room and logged on his smartphone, consumed him daily for more than a year. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

O’Brien is now on the same downward health track as his mother, who fought Alzheimer’s even when she was a caregiver for her husband, who was afflicted with metastatic prostate cancer. “She taught me that I could fight as long as possible and do the best that I could,” O’Brien says. “And then just let go. There are times now when I want to let go, but I’m still able to carry on.”

Carrying on is oftentimes difficult. O’Brien often rages in frustration at what he can no longer do as his mind shuts down. He gets upset when he uses bad judgment, fails to recognize friends, and gets lost in familiar places. “When the day comes that I get up in the morning and put my fingers on the keyboard and don’t know what to do, that’ll be the day I want to check out.”

There are four drugs prescribed for Alzheimer’s symptoms, but they don’t offer much relief. O’Brien takes 23 milligrams of Aricept, the most popular of the memory pills, along with 20 milligrams of Namenda, the last Alzheimer’s drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration, back in 2002. He also takes 20 milligrams of Celexa to tamp down his rage. The 50 milligrams of Trazodone he takes nightly helps him sleep.

O’Brien, a lifelong Red Sox fan, says that God now has him on a pitch count. Even so, there are things he still desperately wants to accomplish, other contributions that he has to make to help people who don’t know about this horrible disease. He regularly addresses community groups on Cape Cod, and often goes to Boston and other New England outposts to talk about Alzheimer’s, urging people to beseech their elected officials to appropriate more funding for research than the meager pittance now set aside by Washington lawmakers.

National Public Radio’s All Things Considered is also chronicling O’Brien’s slow fade to darkness, which has helped spotlight the disease and the distress that it causes for patients and loved ones.

“By spreading awareness, I hope that my efforts will lead to more research and the necessary dollars to fund it that will ultimately lead to a cure,” he says.

O’Brien has a strong Irish Catholic faith, and he’s convinced that he will be going to a better place. “I am not afraid to die,” he says. “What does scare me is the thought of my own three children having to deal with this disease, too. That scares the hell out of me.”

“Though surrounded by my loving family and supported by their devotion, especially that of my wonderful wife and life partner, Mary Catherine, there are times that I just want to go,” he says. “I want to get out of this place. Like my Mom, I want to let go and say that I’m finally done. I fight this urge all the time. But I’m not sure how much longer I can.”