Books |

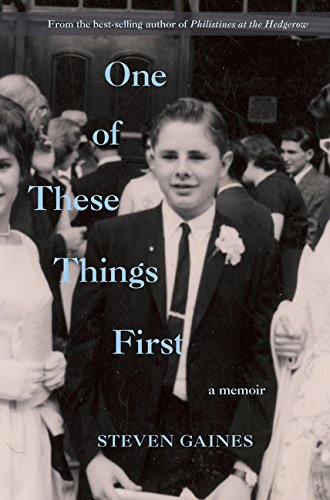

One of These Things First: A Memoir

Steven Gaines

By

Published: Aug 17, 2016

Category:

Memoir

I’ve known Steven Gaines for so long it seems like we were college roommates. Along the way, I’ve read and admired his journalism and his books, which cover turf as varied as Calvin Klein and Hamptons’ real estate. I thought I knew him. I didn’t. Now, four decades in, I do.

“One of These Things First” was a revelation for me. And will be one for readers who have never heard of Gaines. The surprises start in the first chapter. Steven is 15. On this day in 1962, he’s in the back of his grandparents’ ladies’ clothing store. At a window, he rolls up his sleeves. “And then with all my might I punched through the two lower window panes of glass, one fist through each, one fists, two fists…. and I sawed my wrists and forearms twice back and forth across the shards.”

But there’s more to this book than the reality TV set of grim facts, followed by struggle, ending with redemption. Context is everything. And the context of this story is: Jews in Brooklyn, in the last era when life meant family and traditional Jewish values. And here was a kid who didn’t fit in. Who couldn’t fit in. The first chapter is online. Please read it. You’ll see immediately that Steven Gaines is a master storyteller.

The title wasn’t chosen casually. It’s the title of a song by Nick Drake, who died, at 24, of an overdose of an anti-depressant. The lyrics? All the things he might have been. The Steven Gaines story is its opposite, a primer about a man who could not be who he was, but who grew up to succeed at that most important thing: self-acceptance. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Steven Gaines wanted to die because he couldn’t live with himself — because he was gay. It was his shame. It was not his secret. Some kids in Borough Park, “the cognac of Brooklyn,” imitated his walk and his nervous whistle. His parents worried about his obsessive habits. He had a brief triumph when he was cast as a student on a local television show, but he had an “ersatz English accent” and was widely hated. He compulsively swiped a few things, touched certain objects too many times for that to be ignored. When he was fired, he retreated to the back of his grandparents’ store, where he hid in corrugated boxes.

After the suicide attempt, he’s going to be sent to a mental hospital? “I figured it would be an adventure. A lark.” Then he realizes that a mental hospital is anything but. He sees a news report about Marilyn Monroe. She’d spent time at Payne Whitney. Hey, maybe he could go there: “I dreamed Payne Whitney would always be my home, and that I would live forever above the F.D.R. Drive with the rich and neurasthenic.” A loving relative comes up with the money. And suddenly Steven is among the swells.

Now begins a story with two strands: Steven and his fellow patients, Steven and his doctor. With the patients, he finally has a breakthrough: “They were intending to hate me, but they took me under their wing. These were people who were from a different world and they opened it up to me.” Especially Richard Halliday, a theater producer who was married to Mary Martin, famed as Peter Pan on Broadway. Halliday was a major turning point; he told Steven how to dress, what to read. Another patient took him on forbidden expeditions. “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” was never like this.

His Freudian psychiatrist, Wayne Myers, gave him hope. Alas, not realistic hope — Myers believed homosexuality was a disorder and that it could be reversed. And for the next 12 years, he and Steven had sessions devoted to that possibility.

At the end of the book, decades have passed. All these years later, Steven Gaines — the adult, the writer, the gay Jew — is clear-eyed; he gets the joke, pierces the pretense, finds the brightness beyond the cloud. So he visits the old neighborhood, drops in on his psychiatrist. Nostalgia is usually a prelude to sadness. Not here. He recalls the lives of others, the life he had with them. He knows what they meant to him. And who he is. You want to cheer.