Books |

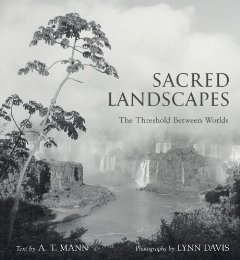

Sacred Landscapes: The Threshold Between Worlds

A.T. Mann, photographs by Lynn Davis

By

Published: Dec 09, 2010

Category:

Spirituality

The books you’d take to a desert island?

The Bible, of course. [Fun fact: Each year, the Bible is the best-selling book in America, with 25 million copies sold.]

Shakespeare. [Because you never got around to “King John.”]

“War and Peace.” [Same reason.]

And, depending on your personal twitches, Proust or Ayn Rand.

Here is a new candidate: “Sacred Landscapes: The Threshold Between Worlds.” [To buy it from Amazon, click here.] It’s a 4.4 pound picture-and-text brick of a book with a thesis that nobody much believed when my hippie pals in the ‘60s first suggested it: Places have power. Sometimes our very distant ancestors grasped that this was so and erected monuments to that power (Stonehenge, Tibetan stupas). Sometimes the power comes from man-made structures that replicate the eternal power found in nature (the Friday Mosque in Isfahan, Iran).

The point: What we have gained through science and exploration is massive. So is what our ancestors on the spiritual path learned from nature. For these places and objects from our distant past contain “inner histories” that resonate with energy. They are, literally, “thresholds” between the world we know and the cosmic knowledge imbedded in our planet. If we wish to slip through that threshold and achieve wholeness — or, more simply, if we wish not to feel so stupid and incomplete all the time — we should spend some time seeking these places out.

Short cut: Dive into this book.

The text is by A.T. Mann, “an architect, author, and astrologer” — quite the varied skill set. He’s written or co-authored twenty books, and along the way he’s learned something important: Vast scholarship works best as narrative. For a book this wise, the writing is wonderfully anecdotal. (Did you know that Aspen trees have an interconnected roots structure? And that, in the American West, there are Aspen forests that occupy hundreds of square miles? And that you could, with some justification, say that the Aspen is the largest organism on earth?) Just as important, Mann is non-judgmental. No culture has his allegiance; he’s a seeker of connections.

Lynn Davis is my favorite photographer. Her black-and-white images are big, and printed big. Good luck finding a person in them — after she started shooting icebergs near Greenland in 1986, her sole interest has been monumental landscapes and the human structures that contain that same energy. (For an overview of her images, click here.) Consumer warning: To see a lot of these images — particularly at night, when it’s quiet and the human craziness fades — is to risk being at least slightly transported.

I can’t think of a recent book that throws off so many ideas. Monocultures are unfortunate. Water molecules degrade in pipes if they hit a 90-degree angle. The Dalai Lama, being greeted by a Hopi in New Mexico: “Welcome home.” A telling photo-spread: Disko Bay, Greenland, in 2000 and again in 2008 — in less than a decade, where did that giant iceberg go?

And then there are the large ideas, which prompt you to consider who you are in the Big Picture. This is deeply personal stuff, and although there is probably a reassuring universality in our longings, I don’t presume to predict this book’s usefulness or effect on you and those you might give it too.

Just this, perhaps: This is powerful book. Handle with respect. And, if the time is right, you may be deeply rewarded.