The Sense of an Ending

Julian Barnes

By

Jesse Kornbluth

Published: Nov 15, 2011

Category:

Fiction

Under 30? Take the day off. Really. The concerns of this book will seem Martian to you.

30-55? This slim book could seem like a preview of coming attractions. But not of your life. Certainly not of my life.

Over 55? Good luck thinking anything but: "How did he know?"

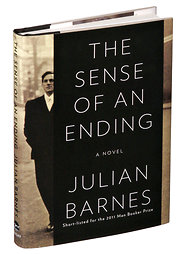

The book in question is “The Sense of an Ending,” which was — if only for its brevity: 176 pages — an unlikely winner of this year’s Man Booker Prize. It’s full of the smart talk, showy learning and brilliantly observed character detail that are the hallmarks of the novels of Julian Barnes. It’s also deadly serious about what we find important as our lives wind down. [To buy “The Sense of an Ending” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

When we meet Tony Webster, he’s an English schoolboy. Bright, his head crammed with quotations and clever ideas, he’s a third of a “book-hungry, sex-hungry, meritocratic, anarchistic” posse of teens growing up around London in the late 1950s. Then Adrian arrives — and he might just be the real deal. "If Alex had read Russell and Wittgenstein,” Tony notes, “Adrian had read Camus and Nietzsche." And Adrian has novel, original thoughts: “I hate the way the English have of not being serious about being serious. I really hate it."

Tony Webster is the narrator, but it’s hard to say he’s the main character. Because much of the pleasure in reading this book is in the surprises that go off like well-timed explosions, all I went to say about the first section of this book is that there are university days and a change in the chemistry of Tony’s friendships, and, of course, a thorny relationship with a young woman named Veronica. Twist my arm, I won’t tell you more.

In the second section of the book, forty years have passed. Tony has had a modest career as an arts administrator, married and divorced, fathered a daughter. Now he’s retired: “I recycle; I clean and decorate my flat to keep up its value. I’ve made my will; and my dealings with my daughter, son-in-law, grandchildren and ex-wife are, if less than perfect, at least settled.”

He wishes. From an unlikely source, he receives a small legacy and a diary. But the diary is not forthcoming. And that leads him to re-examine his past.

"The past is autobiographical fiction pretending to be a parliamentary report," Barnes wrote in his first great novel, “Flaubert’s Parrot.” [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

But how can that be in Tony’s case? He’s had a life in such a minor key that you may ask: What life? And the fact is that he’s investigating what seem to be very small matters — the friendships of his youth, his almost non-existent relationship with Veronica. You would think the facts would be available. And fairly straightforward.

Get closer to the past and you see it’s….strange. Memory is unreliable. Others are unhelpful. What has read like a minor mystery takes on the qualities of a personal thriller. And then the last paragraph of this haunting, disturbing, dazzling book turns the thriller intro a tragedy — a tragedy that everyone who is old enough to have lived long will understand.