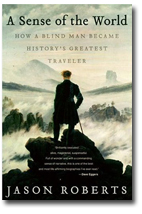

Books |

A Sense of the World

Jason Roberts

By

Published: Jan 01, 2006

Category:

Non Fiction

James Holman was a 21-year-old British sailor with the bad luck to be the man on deck as his ship was buffeted by a winter storm off Nova Scotia. He had the frame of a boy — he weighed just 146 pounds — and not enough of a man’s coat to make a difference. By the end of his watch, he felt stiff in every joint.

The diagnosis was gout. He got some rest, was sent home, received a new assignment — and, once again, was on deck in terrible weather. By 24, he was taking water cures in Bath. But this time, he developed new symptons: shooting pains in his eyes.

At 25, for reasons unknown, he was completely blind.

You can scarcely bring yourself to read about the treatments for blindness in 1810. Start with leeches "applied directly under the eyes." Move on to a "slender spike" inserted in the eye. Luckily for Holman, he wasn’t looking for a cure as much as he was seeking an explanation.

He never found one. But he did find something better: a refusal to live out his days as an invalid on a Navy pension — or, worse, as a beggar. So he acquired an "ordinary walking stick" and a writing machine. He soon learned to get about the streets. And to create documents.

He was now ready to make his way in the world.

The world. Well, he had lifetime tenancy of three rooms. He had 84 pounds a year. He was 26 years old. [To buy the paperback from Amazon.com, click here.For the Kindle edition, click here.]

He enrolled in medical school. He made it look easy — but then, he made everything look easy, so as not to call attention to himself. Still, he took ill. Doctors recommended a rest in the South of France. He taught himself to swim alone. To be self-sufficient — although the wives of fellow travelers were only too happy to help him make ready for bed.

And then comes the huge surprise. This guy wants to go around the world. On the cheap. Without a guide. Traveling through expanses too daunting for the average tourst — who crossed Russia in those days?

What happens on these trips is so beyond our sense of what is possible that you read this book with jaw slack. You can readily understand how his travel writing became immensely popular, why Darwin cited him as an authority — as Holman put it, "I see things better with my feet."

You will see things better if you read this remarkably entertaining and inspiring biography.