Books |

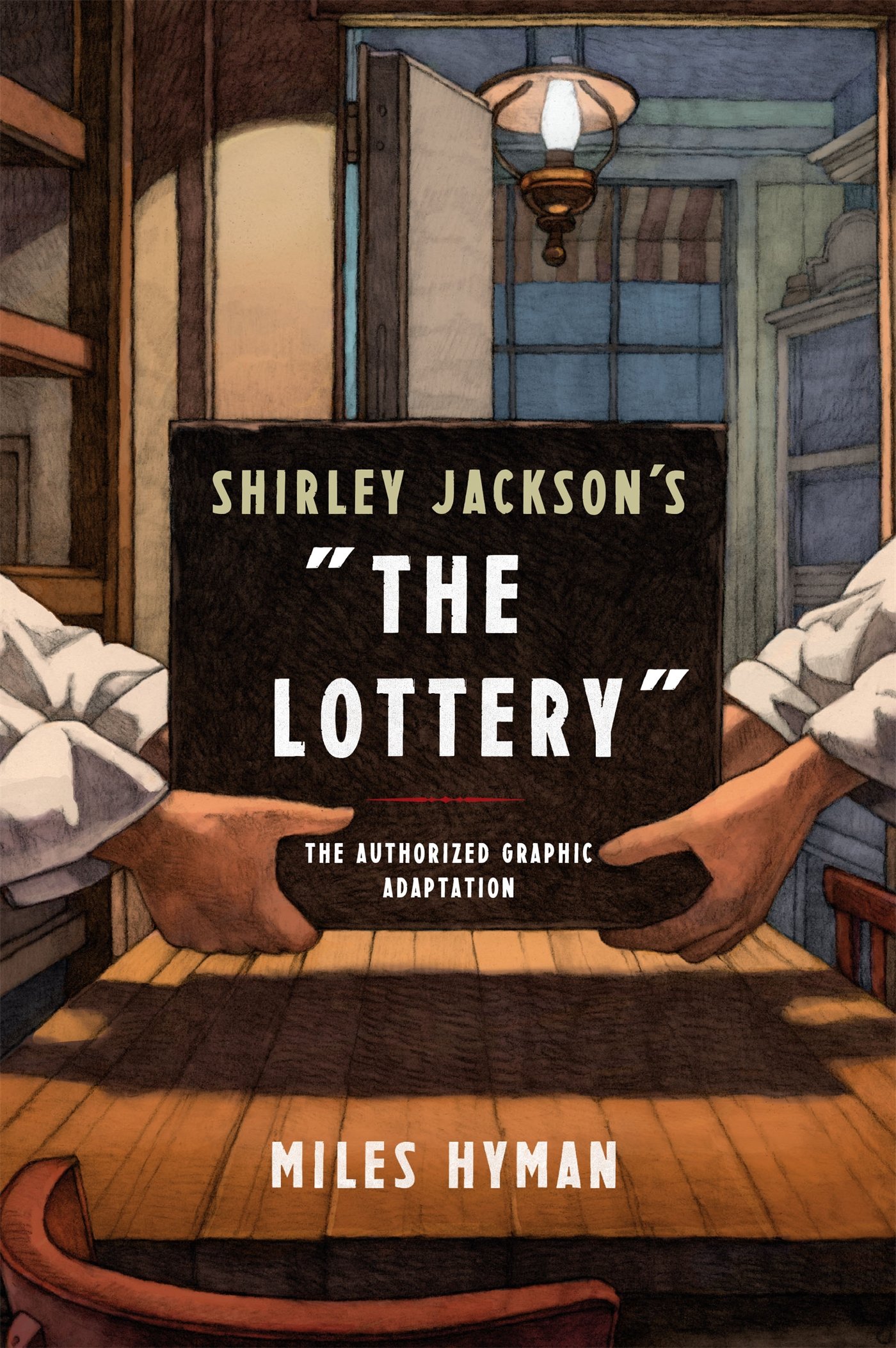

Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” — The Authorized Graphic Adaptation

Miles Hyman

By

Published: Jun 26, 2023

Category:

Art and Photography

Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery” was published in The New Yorker 75 years ago, in the issue of June 26, 1948. It caused an immediate sensation. Some readers wrote to ask if this account of a villager being stoned to death was non-fiction. Others asked for the address of the town, intending to visit and watch the stoning the next year. Jackson’s description of its creation is also astonishing: “I had the idea fairly clearly in my mind when I put my daughter in her playpen and the frozen vegetables in the refrigerator, and, writing the story, I found that it went quickly and easily, moving from beginning to end without pause. As a matter of fact, when I read it over later I decided that except for one or two minor corrections, it needed no changes, and the story I finally typed up and sent off to my agent the next day was almost word for word the original draft.” She doesn’t mention that, later, The New Yorker had suggestions and requested changes. But this is indisputable: “The Lottery” is the most famous story published in America.

Evening in a small rural town. A barn, a church, some houses, a dirt road. A man drives his ‘30s coupe toward Summers Coal, the one lighted window. Another man waits inside. They shake hands and, slowly and solemnly, take a wooden box from a high shelf. They take 300 small pieces and fold them in half, mark one with a large black dot, drop them in the box and lock the box in the safe. At midnight, they tear the date off the paper calendar. It is now June 27, and we are now 19 pages into Miles Hyman’s graphic adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s short story, “The Lottery.”

You’ve read “The Lottery.” We all have. It’s an unforgettable tale of the cruelty that lies just below the surface of our ordinary lives: Each year, on June 27, the citizens of this village — and, we’re told, in others — gather in the square to pluck the folded papers from the box. Heads of households in each family, members of households in each family — no one’s excluded. Each villager takes a folded paper. We watch, studying the faces, as they clutch them. As one, they unfold the papers. There’s a problem, so there’s a short, second drawing. The paper with the black dot is held by Tessie, a wife and mother. The villagers gather rocks… and stone her until she’s dead. The last image? The same as the first: a barn, a church, some houses, a dirt road — a peaceful village.

You can read the Shirley Jackson story here. You can read — and, more important, see — an excerpt from Miles Hyman’s graphic adaptation here and here. I have a personal relationship with Miles Hyman — I’ve known him for six decades, I am a fan of his art, and I was honored when he agreed to draw the butler who is the symbol of this site — but if I knew nothing about him, I know I’d be chilled by what he’s done here. [To buy the hardcover book from Amazon, click here. To buy the paperback, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Miles Hyman is the grandson of Shirley Jackson. He didn’t really know her — she died when he was three — but he grew up in the small Vermont town where she lived and wrote, and she cast a long shadow. In an interview, he shares a memory:

I went to visit high schools when I was thirteen. At one point I was visiting one school and I was in an English class and the teacher introduced me to everyone and said, “This is Miles. You’ll be interested to know that his grandmother wrote the story we read last week, ‘The Lottery.’” And everyone turned around to look at me with horror in their eyes to see who I was. Perhaps that was the point where I became more intrigued by the gothic horror side of her work.

Miles now lives in Paris, where he makes art and illustrates classic novels. His style is a kind of throwback — imagine Edward Hopper or Norman Rockwell telling stories. As a storyteller, he’s more like a film director; his books could be storyboards for a movie. He understands what David Mamet knows: “If you pretend the characters can’t speak, and write a silent movie, you will be writing great drama.” In Jackson’s story, there’s an omniscient narrator. Here, although “The Lottery” is one of the most read and debated pieces of American short fiction, her words are edited; Hyman builds suspense through images. In every panel, we get a portrait of passive conformists that is even more chilling today than it was when Jackson’s story was published in 1948. The Times has published reactions to the story from writers —– Stephen King, David Sedaris, and a dozen more — and the reactions are what you’d expect: fear, amazement, and how did she do that?

We’ve become more addicted to images than we are to stories. If you want to be truly spooked, the graphic novel will take you there. Best not to read it right before bedtime.