Music |

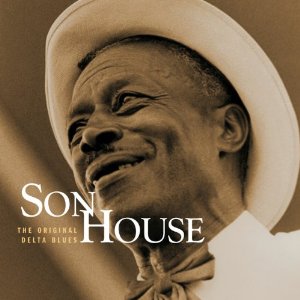

Son House

By

Published: Dec 14, 2010

Category:

Blues

At community ratio station 4ZZZ in Brisbane, Australia, they indulge me by letting me do a monthly historical piece on an artist who has moved on to that big recording studio in the sky, so I was interested in your recent piece on Canned Heat.

The band’s co-founder, Alan Wilson, deserves his place in history for Canned Heat’s catalogue, but I think his greater contribution to blues music may have occurred three years before he headed westward from Boston for a meeting with California record shop employee, music collector and Heat cofounder Bob Hite.

Al played a big part in the 1964 “rediscovery” of Eddie “Son” House, the 1930s Delta blues musician who was the main source of inspiration for both Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters. House, born in 1902, started out as a 15-year-old boy–wonder preacher. Then he crossed over to the dark side, ended up in Parchman farm after a man was killed in a shooting. (“I swear it was in self defense,” he told the judge). His parents got him out after two years, and House took to the road. He cut a few amazing recordings for Paramount in the early 1930s and a few more for Alan Lomax in 1941, but then disappeared, moving north to Rochester in New York State and a job on the New York Central Railway.

Around 1962, blues historian/journalist Dick Waterman and John Fahey began wondering about the fate of a number of 1920s and ‘30s artists who, until then, existed only on scratchy old 78 recordings.

In 1963, they found Bukka White after Fahey sent a letter to "Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi.”

They tracked down Mississippi John Hurt after scouring scoured old maps and Post Office records to find a hamlet called Avalon, the subject of Hurt’s 1927 recording “Avalon Blues.”

In 1964, Wilson — then a 21-year-old music student and blues fan — and Waterman heard that Son House might be living in Memphis, so they set off to find him. They didn’t, but got directions to House’s relatives in Detroit, who in turn gave them an address in Rochester.

And there they found Son House. 62 years old. He hadn’t played for years. He didn’t even own a guitar. Alcohol problems and emerging senility didn’t help either. But he was very interested in a second career.

Waterman gave House a guitar and put him in front of a few coffee house audiences. The results were so disastrous that he asked Wilson to sit with the old man and help him relearn his music, properly like.

In a famous exchange, Wilson, sitting knee to knee with House, said: “In 1930 this is how you played ‘My Black Mama.’”

Then he played it for him.

“And when Mr. Lomax came and recorded you in 1941, you played it this way.”

House, carefully watching Wilson’s hands, exclaimed, “Yeah yeah, there it is. My recollection’s coming back to me now.” [To buy the CD of Son House’s best songs for $7.11 from Amazon, click here. To download the MP3 for $5.99, click here.]

It still raises the hairs on the back of my neck when I think of the 21-year-old Wilson coaxing out the guitar parts that were buried deep in the old master’s subconscious.

It really is true what they say: “Al Wilson taught Son House to play Son House.”

Uninfluenced by the rise of electric blues in the late 40’s and 50’s House was an artist whose music style had been frozen in time — House was a direct link to the delta of the 1930s. With Wilson’s help, his strong voice and aggressive, percussive playing style returned, and he went on to a short but successful second career, appearing before mainly white audiences at college halls, festivals and coffee clubs. House made many great recordings in the mid-to-late 1960s, until Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease forced his second and final retirement in 1976 and, ultimately, death in 1988.

Waterman later said, “All of Son’s successful concert appearances, recordings and him being remembered as having a great second career — all of that was because of Al rejuvenating his music.”

The distance between 1964 and the 1930s is only 30 years, but it’s hard to imagine a rock ‘n roll enthusiast finding a pile of 1970s Stones vinyl in an attic, wondering about the fate of the long forgotten artists, then tracking down Mick, Keith and the band in their late 60s, in quiet obscurity in retirement homes in the south of London.

Unthinkable.

As unlikely, really, as Al Wilson schooling Son House.

BONUS: Jack White on “Grinnin in Your Face”

“I didn’t know you could do that, just singing and clapping…"