Movies |

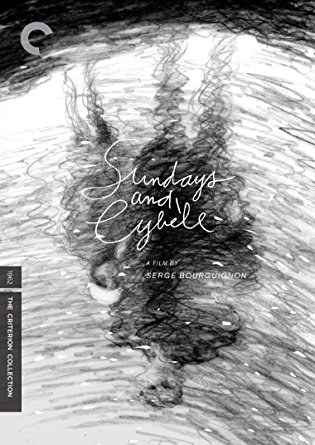

Sundays and Cybéle

directed by Serge Bourguignon

By

Published: May 23, 2017

Category:

Drama

Odds are excellent that you’ve never heard of this movie. But if you’ve seen it, there is no way you’ve forgotten how you felt about it. I saw “Sundays and Cybéle” 55 years ago, and my eyes get misty every time I think of it. And I think of it often: “Sundays and Cybéle” is on my all-time Top 10 list.

I want you to see this film. But not on streaming video. And not on YouTube, where it seems you can watch it for free. I want you to buy the DVD from Amazon. Not for shallow commercial reasons. For aesthetic reasons. This is a black-and-white film so extravagantly beautiful that some images look as if Cartier-Bresson was the cinematographer. And the Criterion DVD delivers those images at the highest level — “Sundays and Cybéle” is simply gorgeous, and you’ll want to share it with people you love a lot, people who can appreciate an overwhelming emotional experience. [The DVD costs $14.40, the price of three unmemorable lattes. To buy it from Amazon, click here.]

“Sundays and Cybéle” won the 1962 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The director was 33-year-old Serge Bourguignon. It was his first film, and his best — he went on to make entirely forgettable features, which is why you’ve never heard of him. But with this film, he shot the moon. “Sundays and Cybéle” was a sensation at Cannes, but no French distributor wanted it. Then it opened in New York, and Bosley Crowther gave it a 10-star review — I reprint it, below — in the Times.

Suddenly, five Parisian theaters that had rejected “Sundays and Cybéle” wanted to show it. Why had critical opinion been divided in France? Because the film is a love story between a 30-year-old man and a 12-year-old girl. It’s a platonic relationship. Still, it’s so unusual, so easy to misunderstand, as to be scandalous.

Pierre had been a pilot in the colonial wars. He has amnesia now, in part because he unintentionally killed a young Asian girl. He lives in Ville-d’Avray, a small town near Versailles, with his mistress, the nurse who treated him when he returned from the war.

Cybèle has a dreadful father. The night he abandons his daughter at a religious orphanage, Pierre witnesses his unspeakable cruelty. He quickly understands that the father has no intention of reclaiming Cybèle; he pretends to be her father, and fools the nuns.

And thus begin their Sunday visits.

Fifty-five years ago, a teenager left the Exeter Street Theatre in Boston in a state of rapture, devastated by the film’s beauty and pain. To see “Sundays and Cybéle” now is, for me, like embracing a long lost friend — a friend who, years before you had any empirical understanding of love, told you a story that opened you up and changed your life. Gratitude for that kind of gift is immense and unending.

Excessive praise? See the film.

BOSLEY CROWTHER’S REVIEW IN THE NEW YORK TIMES

Heaven only knows for what rare virtue New York has been rewarded with the first public exhibition of a French motion-picture masterpiece. But so it has.

And, what’s more, this work of beauty, known here as “Sundays and Cybèle,” which was opened yesterday at the Fine Arts even before its opening in France, is almost by way of being a cinematic miracle. It is the first full-length production of a young writer-director, Serge Bourguignon.

How can one give a fair impression of the exquisite, delicate charm of this wondrous story of a magical attachment between a crash-injured young man who is suffering from amnesia and a lonely little 12-year-old girl? By saying that it is what “Lolita” might conceivably have been had it been made by a poet and angled to be a rhapsodic song of innocence and not a smirking joke.

That doesn’t begin to do it, because the circumstances that bring the young man and the child together and cause them to fall in love—into a kind of love that is exalting and consuming on the part of each—are nothing like the circumstances that fatefully impel the physically obsessed Humbert Humbert toward the treacherous nymphet in “Lolita.”

Here the man is drawn to the youngster when he sees her heartlessly left by her father at a convent in a village outside Paris where he lives.

He presents himself as her father to take her out for walks on Sundays, when he discovers that the father does not intend to return. His feeling for her develops, and hers does for him, as they weekly lose themselves in nature’s vaulted cathedral of trees around a lake.

No, this is not close to “Lolita.” Yet the attachment that grows is not purely idyllic, either. It is clearly compounded of the sexual stirrings in the youngster, the psychic impulses that move her to grope for the male affection she has never had in a loveless, broken home — the faint intimations of womanhood that lead her to throbbing jealousy of the mistress of her hero and to flirting guilelessly with him.

The joyous release of the fellow when he is with the beautiful child is not a mere gush of sentiment, either. It is the poignant expression of a man whose hope and confidence are shattered and who seeks a way to begin his life anew.

How else, then, can one give an idea of the rare quality of this film? Perhaps best by giving an impression of the style of Mr. Bourguignon. It flows somewhere between the terse style of François Truffaut’s “400 Blows” and the natural, serene lyricism of some of the films of Jean Renoir.

For a man whose career has been spent mainly in painting and making film shorts, Mr. Bourguignon has developed a remarkably sensitive camera eye and a taste that, in this film, is flawless. His sense of dramatic form — he helped write this screenplay from a novel by Bernard Eschassériaux, “Les Dimanches de Ville d’Array” — is enhanced by a fine capacity to give subtle graphic expression and clarity to action and moods.

His images of misty Sunday mornings around the magical lake, of circular ripples on the water, at the heart of which the child perceives “our home,” of symbolic objects and behavior that represent longings and fears, are as lovely and subtle and compelling as any sensitive being could wish.

The performances the director has evoked from his small but brilliant cast establish visions in the memory that one can surely never forget. Hardy Kruger is the listless young fellow shaken and vitalized into a weird kind of ecstatic vigor by the strength that flows to him from the child, and Patricia Gozzi is sheer magic as this nimble, refulgent-eyed tot.

Her wonderful changes of expression, her command of emotional states, her ways of suggesting amorous triumph or stabbing jealousy are far beyond the capacity of all but a few adult stars. This is one of the finest performances by a child we have ever seen.

Nicole Courcel is also brilliant as the tender, compassionate mistress of the young man. Her range from initial suspicion through awareness and jealousy to a sweet tolerance of the strange liaison and then to a state of gasping fear as to the social consequences of it is a full spread of drama in itself. Her reaction to the attachment is the reflection of true humanity.

Daniel Ivernel is also helpful as an understanding friend, and Michel de Ré does a fine job as a stubborn realist.

An additional element of beauty and eloquence is the musical score, ranging from Handel to Tibetan music and intruded as oblique suggestion of psychic shadows floating over emotional pools, plus wonderfully keen employment of precise and exquisite natural sounds. One place, in which the sing of pebbles skittering over the ice on a lake points a mood of faint depression, is unforgettable.

Finally, the gathering of anxiety and tension as the drama moves to a smashing, ironic climax completes the emotional purge. The fulfillment of the inevitable comes to the heart of tragedy. Here is truly a picture on a delicate, complicated theme that abides by the piercing adjuration of the mistress: it does not dirty something that is beautiful.