Products |

Supreme

By

Published: Mar 13, 2017

Category:

Clothing

A few weeks ago, in the middle of the night, they got up, dressed quickly and hurried out, taking care not to wake their parents. On the way to Lafayette Street, they met others. When they reached Prince Street, they saw that many had the same idea — there were barricades, and a line.

What had lured these kids to the Supreme store at 4 AM?

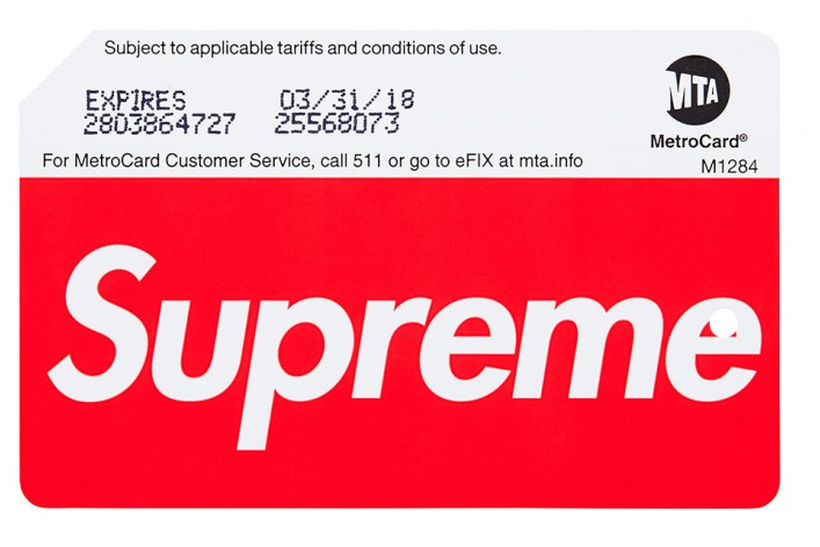

New York City MetroCards. Branded MetroCards — with Supreme, on the back, in bold white letters against a red background. These special cards had been randomly inserted in MetroCard vending machines in eight stations in Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn, and the crowds there were sufficient intense to require police supervision.

But the cool thing, the non-random thing, was to get the Supreme card at the Supreme store. These were not overly useful — the Supreme card, at $5.50, was good for two rides. More could be added at subway stations, but utility was not the point. The red box logo — with “Supreme” in Futura Heavy Oblique, a font familiar to those who have seen Barbara Kruger’s art — was the draw, and a big one at that. Cost of the MetroCard at Supreme: $5.50. On the resale market: much more. On eBay, I saw Supreme-branded MetroCards for sale at $15, a few at $50, and one — good luck with that — for $1,000.

What is Supreme? Why is this brand so hot? Why have you never heard of it? And if you want to buy one branded item, what would it be?

The founder is James Jebbia, a former child actor who began his retail career at Stussy, a store selling branded clothing that appealed to skateboarders and cool kids. He launched Supreme in 1994, again appealing to skateboarders — he displayed the merchandise on wall shelves, so customers could skate around the store.

From the beginning, the philosophy of the store was scarcity. The explanation was that they didn’t know how well an item would sell, so they only made a few. Okay, but if you’re a traditional retailer, you make more when an item sells out. Not Supreme. On the web site, you can see a $136 denim shirt, a $118 flannel shirt, a $118 Oxford button-down. Sweatshirts are $148. A baseball cap is $58. Yeah, you can see them, but when you try to buy them, you learn. Almost everything is sold out.

Crazy prices and small stock should be a recipe for failure, but as critic noted, “When it comes to blind loyalty among consumers, Supreme is the Apple of streetwear.” Like this: The company once put a red clay brick branded with Supreme on sale for $30. In a few hours, it sold out.

No Supreme product is available on Amazon. Which isn’t to say there are no Supreme items for sale there — it’s just they’re all bootleg. The one item that looks passable is the white t-shirt, with the logo splashed across the chest like a large bumper sticker. An aficionado would scorn you kid for wearing this, but for $3 and $4.50 shipping, the bogus t-shirt is a kind of revenge on the brand. [To buy it from Amazon, click here.]

Here’s the bottom line about Supreme: James Jebbia is a marketing genius who has amassed a net worth said to be $40 million by creating excellent products, producing them in small quantities, selling them only in his own stores — his very few stores: New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Tokyo — and then disregarding every rule of merchandising. How do you know when the store is changing seasons? It closes for a few days and the windows are covered with paper.

Customer service seems non-existent. If you have a problem with an order, I get the sense that you can email all you like — you won’t get a response. This doesn’t seem like an accident. Supreme is a party for insiders. If you don’t know the password, you get treated badly.

Bottom line: What started as a kind of cause and then become “a huge accomplishment for street culture” has turned into a youth version of Hermès, which turned its pricy Birkin bags into lust objects you craved but couldn’t acquire.

Supreme releases no more than 15 items at a time. They’re announced on the web site with an on-sale date that’s usually 11 AM on Thursday. Two kinds of customers rush to get in line. Some are fanatics who collect Supreme product as if it were art. And some are resellers and their associates, who do their best to empty the shelves. And because everything sells out as soon as it drops, the resellers can lay the stuff off on Supreme loyalists very quickly and at ridiculous prices. As a reseller says, “At the end of the day, a thing is worth what a fool is willing to pay.”

Because Supreme doesn’t advertise, these resellers are the brand ambassadors. So while the appeal of the brand may be cultish and kidcentric, this marketing strategy couldn’t be more cynical. It’s wasted typing to point this out. To criticize Supreme is to hype it.

The MetroCard caper generated some trenchant vitriol.

As the man says, “All you have to do is throw our favorite logo on a bullet aimed straight at us — and we’ll cock the gun for you.” Another: “The thing that Supreme has done well? They don’t give a shit.” The Facebook comments are specific on this point. This is typical: “How much does it cost for a Supreme employee to not give a fuck about their customers? Nothing at all!”

How does this old fart know about Supreme? I could say, “Hey, I’m not a herb!” The fact is, my daughter just turned 15. And she is a classic smarty — the kind of kid who will tell you, if you’re just catching on to Future, to turn away, quickly, and take a listen to Kodak Black, currently in jail in South Carolia for violating his parole. And one of her friends got up at an ungodly hour to buy her a Supreme MetroCard. Well played, young man. And as for you, my darling child, have I taught you nothing? Sell that thing for $150, already.

BONUS VIDEO