Music |

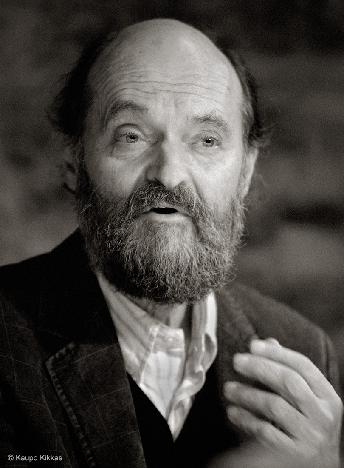

Arvo Part

By

Published: Apr 25, 2016

Category:

Classical

Do you recall how Michael Moore handled the attack on the World Trade Center in ‘Fahrenheit 9/11’?

To the surprise of those who hate him, he did it very, very artfully.

Almost a minute of blank screen, with only sound to tell you what’s happening. Sounds of the planes hitting the Towers — sounds you’ve never heard before — and the human counterpoint: people screaming. Then we see papers blowing in a smoke-filled sky, an abstract image of loss. And music: Arvo Part’s ‘Cantus In Memory Of Benjamin Britten,’ a solemn meditation, with bells and solitary voices and silences between notes.

Whoever picked Arvo Part knew what he/she was doing. Because that is holy music — music that speaks, without intermediaries, to the soul. Which is why, when AIDS first swept across New York City in the 1980s, ‘Cantus In Memory Of Benjamin Britten’ is said to have been a great favorite of dying men in the final weeks of their lives. For this music both acknowledges grief and suggests completion. It is, as Part has described it, ‘like light going through a prism.’ [To buy the CD of ‘Tabula Rasa’ — which includes ‘Cantus In Memory Of Benjamin Britten’ — from Amazon, click here. For the MP3 download, click here. To buy the CD of the ‘Te Deum’ from Amazon, click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

Who is Arvo Part?

First, a child of Estonia, a tiny country across the Baltic Sea from Finland. It became a satellite of the Soviet Union when Part was young. Eventually he left, settling in West Berlin, where he has lived for decades. He’s now in his 70s, with a vast number of compositions and recordings.

But place is not important in accessing Arvo Part — the key fact about him is that he has no real connection to this century. The music tells the story: It is timeless. If you must think of an antecedent, try Bach, for Part and Bach both use religious texts, in Latin. And Part, like Bach, favors a structure that, for all its intricacies, is fundamentally simple — a prayer to God.

In Part’s case, the music is built on what he describes as ‘tintinnabulation’ — a bell-like repetition of a single note. The music doesn’t move forward. It sits. It just…exists. Indeed, if you listen carefully, it becomes the only thing that exists. As Part says:

The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises — and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this. Here I am alone with silence. I have discovered that it is enough when a single note is beautifully played. This one note, or a silent beat, or a moment of silence, comforts me.

This is very evocative, cinematic music — it’s not surprising that, from 1958 to 1967, Part composed music for Estonian film and television. Like the best film scores, his music takes you deeper into the image, makes you look harder and see more. It’s expansive, inspiring; as a conductor has noted, it takes a single moment and spreads it out.

Of the many recordings of Part’s work available, I prefer the ‘Te Deum.’ It is majestic, heartfelt, mysterious, profound, moving. But it’s very personal music — it presses emotional buttons — and so it may feel very different to you. The good news: You will definitely feel something. There is just no way that music of this depth will fail to reach you — the only question is how far inside it will take you.