Books |

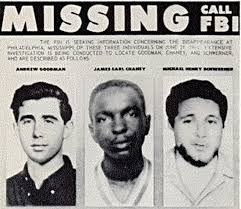

The 1964 Civil Rights Murders: Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney

By

Published: Jun 19, 2017

Category:

History

On June 21, 1964, Andrew Goodman, Mickey Schwerner and James Chaney were murdered in Mississippi. Other civil rights workers were killed in the 1960s, but this was different. Two of the victims were white, and one was from the family that owned the prestige New York store Bergdorf Goodman; this was headline news that stayed in the news. In 1989, on the 25th anniversary of the murders, there was a memorial service in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Before the service, I interviewed veterans of the movement, Mississippi’s Governor and others. My piece, “The ’64 Civil Rights Murders: The Struggle Continues,” was published in the New York Times Magazine on July 23, 1989. It feels sadly relevant today.

—-

Mickey Schwerner and his wife, Rita, had been teaching blacks to read and register to vote for three months in Meridian, Miss., when a dozen crosses were burned in the next county. The Schwerners knew what those crosses signified — and that, contrary to the sheriff’s explanation, no ”outsiders” were involved.

Still, on Memorial Day 1964, Mickey Schwerner drove the 35 miles from Meridian into Neshoba County. “You have been slaves too long,” he told an all-black audience at Mount Zion Methodist Church in Philadelphia. “We can help you help yourselves… Meet us here, and we’ll train you so you can qualify to vote.”

Despite the perils of aligning themselves with a bearded New York City Jew — this was a county with a handful of registered black voters and a sheriff who had already killed two black men ”in the line of duty” — the parishioners of Mount Zion voted to let Schwerner and James Chaney, a black, 21-year-old plasterer from Meridian, establish a base at their church.

Three weeks later, Mount Zion was no more. Members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan pistol-whipped an aging parishioner, assaulted several others and then torched the building, the first of more than 20 churches that would be burned in Mississippi that summer. But their real target — 24-year-old Mickey Schwerner — had eluded them.

On June 21, Schwerner and Chaney returned to Philadelphia to interview the victims. This time, they brought along Andrew Goodman, a 20-year-old college student from New York who had just arrived in Mississippi for what civil rights leaders were calling Freedom Summer. That afternoon, Cecil Price, a Philadelphia deputy sheriff, arrested Chaney on a speeding charge, and his white associates as suspects in the church burning.

According to accounts some of the participants gave to the Federal Bureau of Investigation — testimony that later figured in a Federal trial — the civil rights workers were released from jail late that night, chased by two carloads of armed Klansmen, intercepted again by Price and handed over to the Klan for disposal in the piney woods.

”Are you that nigger lover?” Wayne Roberts, one of the Klansmen, is said to have demanded. ”Sir, I know just how you feel,” Schwerner replied. With that, Roberts shot him in the heart. Next, Roberts shot Goodman. ”Save one for me!” shouted Klansman James Jordan, running over to Chaney and shooting him in the abdomen as Roberts fired into Chaney’s back. Then, for good measure, Roberts put a final bullet into Chaney’s brain. ”You didn’t leave me nothing but a nigger,” Jordan said, ”but at least I killed me a nigger.”

The Klansmen bulldozed the three bodies into an earthen dam under 10 tons of dirt and went home, certain that proof of their crime would never be found. But they miscalculated. These civil rights workers were not like others who had been killed in the same cause — two of them were white. And because this is, as Schwerner’s widow, Rita, has observed, ”a society that values some lives more highly than others,” Washington politicians and New York journalists suddenly cared a great deal about the missing civil rights workers.

The entire nation watched as F.B.I. agents fished a charred station wagon from a swamp, and, acting on a tip, found the three bodies 44 days after the men had disappeared. National attention made instant martyrs of the three young men. It also made Philadelphia close ranks, denying not only involvement in the crime but knowledge of the atmosphere that spawned it. As the administrator of the local hospital told a New York Times reporter, Joseph Lelyveld, that year, ”The people of Mississippi love niggers.”

###

If some Mississippians have had an odd way of expressing their affection for their fellow citizens, it is partly because they have followed the lead of their politicians. Some of these politicians have been Klan members or sympathizers; others have simply been demagogues. Even in the 1960s, Gov. Paul B. Johnson Jr. included a line in his speeches that defined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as ”Niggers, Alligators, Apes, Coons and Possums.”

For a state that branded itself as the most unreconstructed in the nation, Mississippi has undergone a major upheaval in recent years. In 1964, 5,000 blacks could vote; now 600,000 are registered, and they use their ballots. When Ray Mabus, who grew up 45 miles from Philadelphia, ran for Governor in 1987 on a platform of ”basic, drastic change,” whites were 2 to 1 against him — he won the election by carrying the black vote 9 to 1. These days, much is made of the fact that Mississippi has 600 black elected officials, more than any other state. In this climate, the new Governor even welcomed the filming of ”Mississippi Burning,” which was loosely based on the civil rights murders. ”Mississippi is now the South’s most progressive environment,” Governor Mabus told me. ”Because of our history, we went through a crucible others didn’t. And that has enabled us to move on in ways that others haven’t.”

In 1984, the 20th anniversary of the civil rights murders was observed with just one small church service. But with the 25th anniversary approaching, the Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner families began talking about organizing a gathering no one in the Mississippi of 1964 would have believed possible — a memorial to the three men held on the anniversary of their murder in the county where they were killed. Soon the families were joined by activists from Philadelphia, Pa. And in Neshoba County, where there’s no longer a sheriff who wears Western-style holsters and clothes, citizens felt free to propose that Philadelphia, Miss., join this coalition.

Last month, in a bus caravan reminiscent of the early days of the civil rights movement, more than a thousand people traveled to Mississippi from New York, Pennsylvania and the West. The intent of the sponsors wasn’t to open old wounds. On the contrary. After a ceremony to honor the martyrs and a picnic to welcome the town’s visitors, there would, the organizers hoped, be a rekindling of commitment to the future — a ”reverse freedom ride” to New York for a day of voter registration.

But if this observation of the anniversary was significant, it was not because of official events, which too often turned into photo opportunities, nor the speeches, most of which were overlong and clotted with bombast. What mattered was unplanned and unplannable — the intersection of people whose only bond was their common cause. It was in those private moments, away from the shark pool of the press, that the veterans of the 1960’s recalled how it felt to stand alone, and the Mississippi organizers of the memorial explained why they were participating.

###

”I remember how we’d always let Polly Heidelberg march with a picket sign so she’d faint, which she did every time. Once, we took her with us to City Hall. They locked the doors, wouldn’t let us in. And Polly fainted. Well, the only place they could carry her was inside City Hall. You see, God opens doors no man can close.”

In the Meridian church where the veterans of the civil rights movement had gathered to tell war stories, there was a wave of knowing laughter as Charles Young, now a State Representative, looked back to the heyday of the movement. The laughter ended quickly, though, as he spoke of spending nights in this church loft, shotgun on his lap, to protect it from Klansmen.

”That’s right!” shouted a venerable woman in the front pew. ”Say it!”

James Bishop, a Meridian undertaker, next recalled how he insured safe passage for civil rights workers by driving them to meetings in his hearse. ”It’s too easy now,” he said. ”You just sign up to vote. Then you say your vote doesn’t count, so you stay home. And that makes me sick!”

”That’s right!” the woman shouted again. ”Before I take it back, I’m gonna add something to it!”

The woman was Polly Heidelberg, and this, it turns out, is her credo. Now ”way up over 60,” she was born into a family in which education for girls was an economic impossibility. She went to work young, taking care of a white household for $8 a week. At some point in a past about which she’s resolutely nonspecific, she married a railroad porter who introduced her to Roy Wilkins and James Farmer. But she didn’t become an activist, she told me, until January 1964. ”I was a slave until I met Mickey Schwerner,” she emphasized, as we sat on the porch of her home in Meridian. ”And when I met him, I didn’t understand a word he said. But I began to feel free. I asked him if I could work with him at his school. He said, ‘Are you from here?’ I said, ‘No, I’m from everywhere.’ He laughed. ‘Then you be a good friend of mine,’ he said, and we started a family relationship.”

”I brought food and clothes to Mickey and Rita. And I’d go to school. Sometimes I’d say, ‘I’m tired, I can’t do this.’ Mickey would say, ‘You’re doing good — now, what are you bringing for dinner tomorrow?’ And I kept at it. I remember when I learned my 25 words. Mickey jumped up.”

”Political? Oh yes. I was arrested for picketing Woolworth’s. Spent five days in jail. They had me ask the questions at the store because they knew I’d speak up — see, I didn’t want to be a slave anymore. The officer who took us in was so pitiful. He said, ‘Big mama, I hate to arrest you.’ I said, ‘You go on with your job, ’cause I’m goin’ on with mine.’”

Then Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner disappeared.

”When their bodies were found, sorrow rode across Meridian like the dark covered the sun. People could not stand it. We had a church service. We all wore black skirts, but we wore white blouses and carried candles to let people know the light was still burning.”

After that desperate expression of hope, the sadness returned. ”You never saw a lady weep like Rita Schwerner when it was time for her to leave. When we were packing her things, she told us she loved us and our children. She said, ‘Miss Polly, you were the light in my path.’ I said, ‘Rita, you were the light I held.’ And we held each other and cried.”

Mrs. Heidelberg said she had known James Chaney all his life — ”He called me Mama” — so it wasn’t surprising to spot her at the memorial’s first and most intimate event, the unveiling of a massive monument at the Okatibbee Baptist Church Cemetery in Meridian, where Chaney is buried. It was designed on a grand scale for good reason — Chaney’s first two headstones were stolen. Later this summer, an eternal flame will be lighted at its base. For now, the inscription on the stone is sufficient: ”There are those who are alive, yet will never live. There are those who are dead, yet will live forever. . . .”

At the gravesite, there were prayers and speeches. After some of them, a spectator with no prior knowledge of Chaney’s death might have concluded he was a fireman who perished trying to save a child — the words were about the voluntary giving of a life, not of its violent taking. In that muddle, Polly Heidelberg’s gesture was pure and unequivocal: she knelt by the grave and touched her hand to the sun-warmed stone. ”I wanted him to know,” she said, ”that his grandma still loves him.”

###

The murders of the civil rights workers may, as the editor of The Neshoba Democrat, Stanley Dearman, suggests, ”never go away,” but that doesn’t mean they’re much discussed in Philadelphia even today. No one, for instance, is likely to talk about the fact that although their identities were commonly known, none of the Klansmen involved in the murders was ever charged by the state. The only prosecution was in a Federal court, where 19 men, including Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price and Klansman Wayne Roberts were tried for conspiring to violate the civil rights of the victims. James Jordan, contending that he had served as a lookout and was not involved in the killings, became a Government informer and pleaded guilty. In 1967, his testimony helped convict 7 of the 19, including Price and Roberts. None spent more than six years in prison.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan gave a campaign speech at the Neshoba County Fair in which he pointedly endorsed states’ rights; last year, Michael Dukakis spoke there without mentioning the county’s most notorious event. In the town itself, there is no acknowledgment of the killings in the local history exhibits at the high school. Until last month’s memorial, only two plaques commemorated Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, both at black churches. The one at Mount Zion — proclaiming ”Out of one blood God hath made all men” — was set safely within the rebuilt church. It was difficult, even on the morning of the memorial, to find a poster in the business district announcing the service or the picnic. And few whites from Philadelphia participated in the events.

So the question of the day was what the Governor and Secretary of State would say at the memorial service on the dusty lawn outside Mount Zion Church. Would they confront the sinister streak in Mississippi’s character that made these murders possible and, even now, almost unmentionable? Would either allude to State Attorney General Mike Moore’s announcement four days earlier that he was considering reopening the investigation and, possibly, moving to indict the killers for murder?

For Secretary of State Dick Molpus, 39, the issue of unacknowledged guilt and inadequate punishment strikes close to home. He was born in Philadelphia. His grandfather came here in 1905, the year the railroad reached the town, and established a lumber business. Every summer, from the time he was 10, Dick Molpus worked in that lumberyard side by side with blacks and uneducated whites.

”I got to know and respect them,” he said in his office across from the State Capitol, in Jackson. ”These were low-paying jobs stacking lumber in the broiling sun, but they all wanted something better for their kids.” His values were formed during those summers, he said, and by his parents, ”who were essentially conservative people, but who taught me about dignity and respect.”

Molpus was 14 when the civil rights workers were killed. ”I remember a lot of fear. Not just from the physical violence of the nightriders, but from the economic pressure put on anyone who spoke out. My father was threatened because he refused to fire several of his black workers who went to register to vote.”

At 18, Molpus worked in the gubernatorial campaign of William F. Winter, who was tagged as a liberal and was defeated. Winter ran again, and lost again. Finally, when Molpus was 30 and married and running the family business, Winter won – and offered him a job.

In 1980, Mississippi still had no public kindergartens and no compulsory schooling. ”Sixty-five-hundred children each year didn’t go to first grade!” Molpus said. ”We went to work changing that. We got beat in the Legislature in 1981 and 1982. People made fun of us, called us ‘the boys of spring,’ so we took that Education Reform Act — the first in America — to the people. In Oxford, we expected 400 at the meeting. We got 3,000. It was like that all over the state. In December of 1982, there was a special session of the Legislature. Ten days later, the act passed. They called it the Mississippi Christmas Miracle. A lot of us who’d worked on it thought it wouldn’t pass, and then we’d quit and run for office. When it won, we were used to the idea of running, so three of us ran for state office anyway – and to our surprise, all three of us won.”

Molpus had campaigned for Secretary of State by pledging to be a watchdog. After he took office, his plan started at home: ”My wife and I decided that, with proper leadership, white middle-class support could return to the Jackson public schools — we never wanted to send our children to a private academy. A number of parents with similar views banded together when our children went to first grade, and we all sent our kids to a school that was 75 percent black. Now that school is about 65 percent white, and it’s grown from 240 to 540 students. And that shift is rippling across Jackson.”

Last winter, Molpus was approached with a fresh challenge: a request to be the honorary chairman of the commemoration in his hometown. Why did he accept? ”There are times in life when you have to step up, and this was one. And I saw this wasn’t a front for a superficial P.R. job. Everyone from the Indian chief to the Chamber of Commerce was involved. That was invigorating. That local committee of 33 people who’d never sat down together before — they found they kind of liked one another.” Which left only the question of what he was going to say. ”I thought that my community has been looking for the last 25 years for a way to address this. And what we had here was an opportunity for a cathartic experience.”

With his blond hair, open face and tasseled loafers, Dick Molpus looked more like a frat boy from Ole Miss than the first Mississippi official ever to address the families of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner. When he got up to deliver the short speech that had taken him three weeks to write, his voice was clear and flat. He made a ritual statement of welcome, then announced that he had a special word for these families. No one perked up.

Dr. Carolyn Goodman, Andrew’s mother, and her surviving son, David, were seated behind him on the platform, as were James Chaney’s daughter, Angela Lewis, and his brother, Ben. Nor could Molpus easily see Mickey Schwerner’s brother, Steve. But he could, by making a half-turn, look directly at Schwerner’s widow, now Rita Bender, whose beatific smile suggested that she had long ago reached some inaccessibly private understanding.

”We deeply regret what happened here 25 years ago,” Molpus said. ”We wish we could undo it. We are profoundly sorry they are gone. We wish we could bring them back.”

Rita Bender’s smile had evaporated. Her eyes were wide open. It seemed that she and Molpus were alone on the platform, that the deepest chasm of all was, through these simple words of apology, finally being breached.

Molpus paused. Then he made his apology even more specific. ”Every decent person in Philadelphia and Neshoba County and Mississippi feels exactly that way,” he said.

Applause began — brief applause, to be sure, but from every corner of the churchyard — and Molpus’s voice gained strength. He acknowledged that what was being marked here was, fundamentally, a human tragedy, that what happened here was no abstraction. He spoke of this ”dark corner” of the county’s past. And, once again, he turned back to the families. ”God bless each of you,” he concluded. ”We are genuinely glad to have you here.”

Then, his shirt still dry in the hundred-degree heat, he sat down and sealed his remarks by shaking hands with his friend the Governor.

###

Those who had traveled to the memorial by bus were having their own experience: the social pressure of a temporary group, the strain of driving all night, and, most of all, the emotional tension generated by the contradictions that thrive in today’s Mississippi. At the Holiday Inn in Meridian, headquarters for the contingent from the North, it was possible to flick on a cable television channel the night before the memorial and watch ”Mississippi Burning” — or change the channel and watch a Mississippi-made documentary called ”Did They Die in Vain?” Lawrence Rainey, the Neshoba County sheriff in 1964, gave a rare interview for that program, commenting mostly about the Hollywood film. ”Uncalled for, to make a movie like that,” said Rainey, who is now a security guard at a shopping mall in Meridian. ”There was never but one black building burned in Neshoba County. . . . There wasn’t one civil rights worker arrested and beaten by the Sheriff’s Department. . . .”

Outside, Rainey’s unrepentant attitude was echoed by the young white Mississippians who cruised the Holiday Inn parking lot, taunting their unwanted visitors. At about the same time, in nearby Selma, Ala., two white teen-agers from the California contingent went out for a walk and found themselves being arrested, along with five Selma blacks, for loitering. The Californians were soon released, but the local blacks spent the night in jail.

The disparity between rhetoric and reality unnerved some of the bus riders, but it seemed to have little effect on 22-year-old Angel Gutierrez, who had come from Los Angeles with a group of sophisticated young activists. Gutierrez was sophisticated in other ways. When he was 6, he explained, he was hanging out with gang members; by age 9, after three years in a foster home, ”My knife became my best friend.”

When Gutierrez was 12, he was charged with three counts of attempted murder and sent to a correctional facility for four years. By 21, after another stint in prison, he says he realized the pattern would only repeat itself. He applied to the Los Angeles Conservation Corps, and although he says he never stepped inside a classroom until the sixth grade, he has started to work toward a high school diploma. With the change in attitude have come new dreams:

”Right now, I’ve got 15 guys in my gang working with me to put murals up over graffiti — I’m putting my new colors over my old ones. The gang members I fought against, I talk to them now. These three rival gang leaders and I want to have a youth center, a little building on neutral ground in South Central L.A. We want to let kids know it’s O.K. to work with other gangs. Then you move on to education, to jobs. We want to show kids there’s a way out.”

What did Gutierrez take from his experience in Mississippi? ”I’m curious,” he said. ”I’m here to learn more about politics.” As we talked, one of the leaders of his group stood nearby. She was beaming. Angel Gutierrez might not know it, but his immediate plans fit in exactly with the kind of activism the organizers of the Mississippi memorial were hoping to generate.

When Pete Talley became president of the Philadelphia, Miss., chapter of the N.A.A.C.P. three years ago, there was only one other official member and no youth organization. Now, he says, there are 300 adult members and 120 young people involved. ”If you address real problems, people will buy into your organization whether they like you or not” is how he explains the resurgence of interest in the N.A.A.C.P. in his town, where the mere fact of membership was once a militant act. Dick Molpus offered a simpler explanation. ”Pete Talley is no ‘yes’ guy,” he told me.

The man who is the most visible force for change in Neshoba County has a scrubby beard and ageless gaze that make him seem both older and younger than his 37 years. He also has a sense of humor. ”Well, I have always been on the wrong side of something,” Talley said with a laugh, when I told him of Molpus’s assessment. ”I always see areas of improvement. And I can’t stand people who just talk about improvements. Talk, talk, talk — and then nobody rolls his sleeves up.”

Talley’s first confrontation with white power in Neshoba County came in 1970, his senior year of high school. His school had been integrated that year, and, due to different standards, some of his friends didn’t have enough credits to graduate. He threatened a boycott of the graduation exercises. ”I organized a group to meet with the principal,” he recalled. ”He was conciliatory, even frightened. That amazed me. He said he’d have the records searched. And two of my friends did graduate.”

Talley was married a year later, and soon became a father. To support his family, he took a job with the telephone company. After 10 years, he began to think of moving away from Neshoba County: ”I didn’t want my children to know only this. But my supervisors reminded me I’d lose my seniority in a new town, so I stayed on here. And it’s been good. Would you believe the phone company told me that if I need time for my N.A.A.C.P. work, they’d make arrangements — within reason — for me to do it?”

That work tends to focus on children and education. ”Forty percent of the black kids here are in the slower groups at school,” he said. ”I want to decrease that to 10 percent. I can’t do that by saying, ‘They’re discriminated against.’ I’ve got to get results and work on racism along the way. And that takes some changes in attitude. Before the 1980’s, parents knew racism existed, but they pushed their kids to excel. We’ve got to get that spirit again, got to put in the work, work twice as hard, look to succeed — we can’t use racism as an excuse.”

In the last few years, the Philadelphia N.A.A.C.P. has started a tutoring program, raised money to send children who have never left Mississippi on out-of-state vacations (”If you stay in one area always, your mind becomes narrow”), and opposed corporal punishment in public schools. In the process, Talley has set an example for his three children.

”I’m afraid my daughter, Phonecia, has turned out just like me,” Talley said with a smile. ”She’s 16 now, and in one of her classes they were discussing racial issues. So she stood up and gave a speech. When she sat down, the teacher said, ‘Thank you, Pete Talley.’ ”

Talley was 12 in the summer of 1964. He was, he recalled, ”curious and amazed” by the murders. Mostly, though, he was scared: ”This county was ruled by terror. It was like a police state.”

A quarter of a century later, as he sat on the lawn of Neshoba County High School and watched an audience of out-of-state visitors dutifully listen to yet another round of speeches at the town-sponsored picnic, he had some reservations about the claims of ”25 years of change.”

”Let’s put this day in perspective,” he said. ”This event is an opportunity for a person who’s a borderline racist to change. It’s an excuse to change. For me, it’s something else. These last six months, my wife’s been a widow. Last night, I told her, ‘After tomorrow, it will be different.’ She said, ‘After tomorrow, you’ll find something else.’ I had to agree, because working on this memorial has matured me. I’ve learned a lot about people and about what’s possible. I intend to move in that direction, and I intend to do it often — and soon.”

So Pete Talley wasn’t going to ride one of the buses going north. Instead, he would be meeting with lawyers to work on a lawsuit against Neshoba County. ”Eighteen percent of the voters in this county are black, and yet there’s no black representation in the county,” he said. ”To me, that suggests a need to redistrict.”

The next morning, as Talley drove several teen-agers to the bus, he saw something painted across four downtown buildings. The letters were red. They were two feet high. The message was simple: ”KKK.”

Around Philadelphia, the reaction to that warning was fairly predictable. At Motor Supply, one of the businesses tagged with the Klan graffiti, an employee suggested it was probably ”a bunch of kids playing a prank.” At The Neshoba Democrat, whose offices were also defaced, the editor was less sure. ”The day before the memorial, someone called the office and left a message that ‘We don’t like what you’re printing,’ ” Stanley Dearman said. ”And we also found some Klan tabloids on our steps.”

For his part, Pete Talley was bracingly unconcerned. ”I just thought, ‘Good gracious, that’s interesting,'” he told me. And, he reported, he went on and filed his lawsuit.