Books |

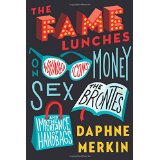

The Fame Lunches: On Wounded Icons, Money, Sex, the Brontës, and the Importance of Handbags

Daphne Merkin

By

Published: Sep 17, 2014

Category:

Non Fiction

Daphne Merkin is frighteningly intelligent. You only have to read a few paragraphs of her writing to know that she’s read, heard and seen everything written, recorded and filmed, and that, for good measure, she has a point of view about her subject that is dramatically different from every other writer. But Daphne Merkin is not only deeply smart, she is deeply troubled. She’s the queen of Too Much Information, though in her case the oversharing is the point.

She was, she tells us, born into a family of casually Orthodox Jews. They Merkins were rich — they lived in a Park Avenue duplex, they had a house staff — but money somehow didn’t seem plentiful. Her father was successful and distant. She could never get close to her mother; young Daphne had a “sense of not having been loved — or, to put it more precisely, responded to in a way that felt like love.” At 5, she began “to be apprehensive about what lay in wait for me.” At 8, she was “wholly unwilling to attend school, out of some combination of fear and separation anxiety.”

But she could write. Lord, could she write. When she was 21, she reviewed a book by Jane Bowles. Woody Allen wrote her a fan letter: “You’re wasting your gifts on reviewing.” They became friends. Many years later, over lunch, she told him she felt more depressed than usual. With that, as she writes in this collection of pieces, the interrogation began:

How depressed? he immediately wanted to know. Quite depressed, I said. Did I have trouble getting up in the morning? Lots, I answered. Did I ever stay in bed all day? No, I said, but it was often noon before I got out of my nightgown. But of course I continued to write, he said. I answered that I hadn’t written a word in weeks. He looked quite serious and then gently asked me if I had ever thought about trying shock therapy. Shock therapy? Yes, he said, he knew a friend — a famous friend — for whom it had been quite helpful. Maybe I should try it.

Sure, I said. Thanks. I don’t know what I had been hoping for — some version of come with me and I will cuddle you until your sadness goes away, not go get yourself hooked up to electrodes, baby — but I was slightly stunned. More than slightly. I understood that he was trying to be helpful in his way, but it fell so far short. We shook hands on Madison Avenue and then gave each other a polite peck, as we always did. It was sunny and cool as I made my way home, looking in at the windows full of bright summer dresses. Shock therapy? It wasn’t as though I hadn’t heard of it or didn’t know people who had benefited from it. Still, how on earth did he conceive of me? As a chronic mental patient, someone who was meant to sit on a thin hospital mattress and stare grayly into space? Didn’t he know I was a writer with a future, a person given to creative descriptions of her own moods? Shock therapy, indeed; I’d sooner try a spa.

It suddenly occurred to me, as I walked up Madison Avenue, that it might pay to be resilient, if this was all being vulnerable and skinless got you. People didn’t stop and cluck over the damage done unless you made it worth their while. Indeed, maybe it was time to rethink this whole salvation business. Or maybe I was less desperate, less teetering on the edge, than I cared to admit. Now, that was a refreshing possibility.

Now that I’ve suggested the psychological terrain — and these are just the top notes, expressed as vulgar journalism — what about “The Fame Lunches: On Wounded Icons, Money, Sex, the Brontës, and the Importance of Handbags,” Daphne Merkin’s new collection of essays? There are 45 of them, and the topics are, as they say, wide-ranging. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Merkin is extremely conscious of surface appearance, especially her weight, so there’s an essay called “In My Head I’m Always Thin.” (To read it, click here.) “Our Money, Ourselves” tracks her family’s public philanthropy and private tightness: “At some point I took to muttering darkly to my mother that charity began at home, but she would always fix me with a contemptuous look and ask, ‘And what exactly is it that you lack?’ She managed to make me feel ungrateful and grabby at once.”

There are meditations on stars, most of them damaged icons ripe for her healing analysis — Marilyn, Michael, Truman, Courtney. Her take on Princess Diana’s marriage will suggest the tone: “I find myself wondering how Diana’s life might have turned out if she and Charles had bonded over their shared lack of childhood, their virtual abandonment as children. …What would have happened if they had the patience (on his side) and endurance (on hers) to address their mutual longings for love and nurturance in each other?”

There are book reviews, many of them learned, some of them esoteric. Zingers appear — on John Updike: “He began to seem like a man who always wore a hat to work.” — but the general reader may feel lost. No problem. This isn’t a book you read cover-to-cover in an evening. It’s a book you dip into, reading what you like, skipping what doesn’t appeal.

Tina Brown told Daphne Merkin, “The art of self-exposure is not simply catharsis.” True, especially for Daphne Merkin. I know her just well enough to believe she found only modest catharsis in writing these pieces. She’s after something bigger, smarter, grander. And in her endless distress, she often finds it.