Books |

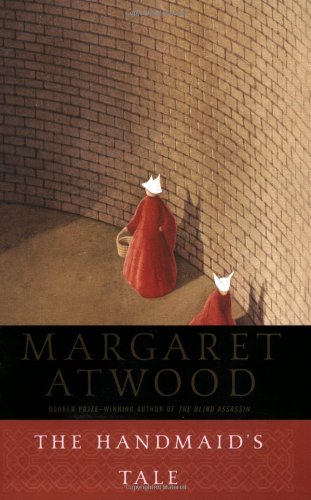

The Handmaid’s Tale

Margaret Atwood

By

Published: Apr 06, 2017

Category:

Fiction

Washington, D.C.: A judge understood that a cesarean section might kill a seriously ill 27-year-old woman who was 26 weeks pregnant. Still, he ordered that she undergo the procedure. Both the woman and her baby died.

Iowa: A pregnant woman fell down a flight of stairs and went to the hospital. The hospital reported her to the police, who arrested her for “attempted fetal homicide.”

Utah: A woman gave birth to twins. One died. Health care providers argued that she was delivered of a stillborn because she had delayed having a cesarean, and she too was arrested for fetal homicide.

Louisiana: A woman went to the hospital because she was bleeding vaginally. She was convicted of second-degree murder and spent a year in jail before medical records proved she’d had a miscarriage.

South Carolina: A pregnant woman jumped out a window. Her suicide attempt failed. Because she lost the pregnancy, she was jailed for homicide by child abuse.

These are not incidents from the Dark Ages — they’re recent. And as Lynn Paltrow and Jeanne Flavin write in The New York Times, they’re just a few examples of the “progress” that “pro-life” activists have made in their campaign to strip American women of their rights:

We can expect ongoing efforts to ban abortion and advance the “personhood” rights of fertilized eggs, embryos and fetuses. But it is not just those who support abortion rights who have reason to worry. Anti-abortion measures pose a risk to all pregnant women, including those who want to be pregnant. Such laws are increasingly being used as the basis for arresting women who have no intention of ending a pregnancy and for preventing women from making their own decisions about how they will give birth.

“Preventing women from making their own decisions about how they will give birth” is the engine of the plot of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel, “The Handmaid’s Tale.” In the novel, at some point in the future, the “Sons of Jacob” stage an attack — which they blame on Islamist terrorists (in 1985, how prescient was that?) — on Washington. They kill the President and many in Congress, take over the government, and, in the interest of restoring order, re-engineer the United States into an Old Testament theocracy. Women’s rights no longer exist. Women are now breeders. They have no other purpose.

One way or another, you’ve heard of “The Handmaid’s Tale.” For decades, the title has been feminist shorthand for the kind of future that’s likely for women if Christian fundamentalists have their way. Because it’s graphic about the sex that handmaids are permitted — the man’s actual wife is on her back, legs spread, and the handmaid lies over her, legs spread, as the man donates his seed — school boards across the country have banned it. It has won awards. And it’s sold millions of copies. [To buy the paperback, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. To buy the audiobook — read by Claire Danes, said to be terrific — click here.]

Thanks to “The Hunger Games,” other dystopian novels and footage of terrorist bombings and beheadings, we’re familiar with horrific cruelty. But even by contemporary standards, “The Handmaid’s Tale” still has the power to shock.

Let’s drop in on the Republic of Gilead, the former United States, specifically in the community around Cambridge, Mass., where once there was a Harvard. Our narrator is Offred, that is, “of Fred, ” the head of her community. The handmaids, dressed all in red, their faces hidden by what are essentially blinders, are allowed to go to town for errands, but they must travel in pairs and the entire area is walled because there is, of course, a continuing terrorist threat. Bodies hang along the Wall: men who have been “salvaged” for unspecified crimes. The meat store is called All Flesh.

And flesh is all. Fertile flesh. It is of crucial importance that a handmaid can bear children. Once she can’t, she becomes an “unwoman” and may be sent elsewhere to clean areas spoiled by nuclear waste. Love? Doesn’t exist. There is only sex, and then only with a sanctioned “commander.”

But the difficulty of repopulating the community when men are often sterile and women are often infertile is not what the problem really is. Reducing women to incubators serves a larger goal: sustaining male patriarchy. And the easiest way to do that is by coercion, by controlling women.

Science fiction? That’s how this novel is generally labeled. Atwood resists that:

I made a rule for myself: I would not include anything that human beings had not already done in some other place or time, or for which the technology did not already exist. I did not wish to be accused of dark, twisted inventions, or of misrepresenting the human potential for deplorable behavior. The group-activated hangings, the tearing apart of human beings, the clothing specific to castes and classes, the forced childbearing and the appropriation of the results, the children stolen by regimes and placed for upbringing with high-ranking officials, the forbidding of literacy, the denial of property rights — all had precedents, and many were to be found not in other cultures and religions, but within western society and within the “Christian” tradition itself.

Could pregnant women lose their rights in our country now? It seems… crazy, yes? It certainly seemed so to the distinguished novelist Mary McCarthy, who reviewed “The Handmaid’s Tale” in the New York Times in 1986. She destroyed the book:

I just can’t see the intolerance of the far right, presently directed not only at abortion clinics and homosexuals but also at high school libraries and small-town schoolteachers, as leading to a super-biblical puritanism by which procreation will be insisted on and reading of any kind banned.

McCarthy’s conclusion: “’The Handmaid’s Tale’ doesn’t scare one.”

It scared me.