Books |

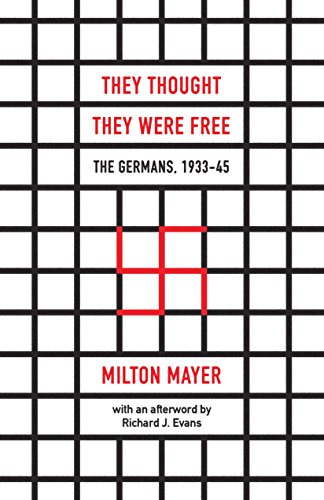

They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45

Milton Mayer

By

Published: Apr 01, 2024

Category:

Non Fiction

SUPPORTING BUTLER: Head Butler no longer gets a commission on your Amazon purchases. So the only way you can contribute to Head Butler’s bottom line is to become a patron of this site, and automatically donate any amount you please — starting with $1 — each month. The service that enables this is Patreon, and to go there, just click here. Thank you.

LAST WEEK IN BUTLER: Holiday Weekend Butler, John O’Donohue. Tallis Scholars: Miserere. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin.

We are one nation, divided, and in no danger of reconciliation. How did we get this way? Start with the Civil War, which was, depending on where you lived, about the humanity of Black people or a narrow definition of State’s Rights. More recently, inject the cynicism of some politicians and the Murdoch media. But maybe the explanation is simpler: people who are poor and isolated will always be ripe for exploitation — like these Germans before World War II.

In 1935, a Jewish reporter from Chicago went to Germany in the hopes of interviewing Adolph Hitler. That didn’t happen, so he traveled around the country. What he saw surprised him: Nazism wasn’t “the tyranny of a diabolical few over helpless millions” — it was a mass movement.

In 1951, the Jewish reporter from Chicago returned to Germany. This time Milton Mayer had a different goal: to interview ten Nazis so thoroughly he felt he really knew them. Only then, he believed, might he understand how the Germans exterminated millions of their fellow citizens.

He interviewed ten Germans at such length they became his friends. Reading his daughter’s memories of her father, I can understand how that happened. “His German was awful!” wrote Julie Mayer Vogner. “And this was a great aid in the interviews he conducted: having to repeat, in simpler words, or more slowly, what they had to say made the Germans he was interviewing feel relaxed, equal to, superior to the interviewer, and this made them speak more freely.”

In 1955, Mayer published “They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45.” It was a disturbing book then. It still is. For one thing, Mayer had only the warmest feelings for the men he interviewed:

I liked them. I couldn’t help it. Again and again, as I sat or walked with one or another of my ten [Nazi] friends, I was overcome by the same sensation that had got in the way of my newspaper reporting in Chicago years before [in the 1930s]. I liked Al Capone. I liked the way he treated his mother. He treated her better than I treated mine.

The ten interviewees were quite the diverse crew: a janitor, soldier, cabinetmaker, Party headquarters office manager, baker, bill collector, high school teacher, high school student, policeman, Labor front inspector.

“These ten men were not men of distinction,” Mayer notes. “They were not opinion makers…. In a nation of seventy million, they were the sixty-nine million plus. They were the Nazis, the little men…” [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

What didn’t they know, and when didn’t they know it?

They did not know before 1933 that Nazism was evil. They did not know between 1933 and 1945 that it was evil. And they do not know it now [in 1951]. None of them ever knew, or now knows, Nazism as we knew it, and know it; and they lived under it, served it, and, indeed, made it.

And none ever thought Hitler would lead them into war.

Why not?

— They had never traveled abroad.

— They didn’t talk to foreigners or read the foreign press.

— Before Hitler, most had no jobs. Now they did.

— The targets of their hatred had been stigmatized well in advance of any action against them.

— They really weren’t asked to “do” anything — just not to interfere.

— The men who burned synagogues did not live in the cities of the synagogues.

— Hitler was a father figure, right to the end. (He was “betrayed” by his subordinates.)

The more you read, the more your jaw drops. How many people did it require to take over a country? “A few hundred at the top, to plan and direct…. a few thousand to supervise and control…. a few score thousand specialists, eager to serve…a million to do the dirty work….”

There’s more, much more. Some of it is quite specific to the German character (yes, there apparently are national characteristics). And some of it might stand as universal metaphor. If you’re not a history buff, that’s the reason to read this book — it’s a revealing study of “little” people, people who seem insignificant, good citizens who do as they’re told.

Who knew nobodies could be so important — or so dangerous?

—-

To read an excerpt of “They Thought They Were Free”, click here.

Here’s a sample:

What no one seemed to notice,” said a colleague of mine, a philologist, “was the ever widening gap, after 1933, between the government and the people. Just think how very wide this gap was to begin with, here in Germany. And it became always wider. You know, it doesn’t make people close to their government to be told that this is a people’s government, a true democracy, or to be enrolled in civilian defense, or even to vote. All this has little, really nothing, to do with knowing one is governing.”

“What happened here was the gradual habituation of the people, little by little, to being governed by surprise; to receiving decisions deliberated in secret; to believing that the situation was so complicated that the government had to act on information which the people could not understand, or so dangerous that, even if the people could understand it, it could not be released because of national security. And their sense of identification with Hitler, their trust in him, made it easier to widen this gap and reassured those who would otherwise have worried about it.”