Books |

Eric Hoffer: The True Believer

By

Published: Jan 06, 2021

Category:

Psychology

SUPPORTING BUTLER: You can contribute to Head Butler’s bottom line by becoming a patron of this site. It’s simple: each month, you automatically donate any amount you please — starting with $1. The service that enables this is Patreon, and to go there, just click here. Thank you.

LAST WEEK IN BUTLER: Weekend Butler. Boubacar Traore

—–

As Donald Trump’s first criminal trial begins, I wondered if a longshoreman who wrote books but barely went to school would have any chance of getting on the jury….

Eric Hoffer believed in short. Anything that needs to be said, he believed, could be said in 200 words. He might, for example, explain what happened at the Capitol on January 6, 2021 in 192 words:

All mass movements generate in their adherents a readiness to die and a proclivity for united action; all of them… breed fanaticism, enthusiasm, fervent hope, hatred and intolerance; all of them are capable of releasing a powerful flow of activity in certain departments of life; all of them demand blind faith and single hearted allegiance. All movements, however different in doctrine and aspiration, draw their early adherents from the same types of humanity; they all appeal to the same types of mind.

Though there are obvious differences between the fanatical Christian, the fanatical Mohammedan, the fanatical nationalists, the fanatical Communist and the fanatical Nazi, it is true that the fanaticism which animates them may be viewed and treated as one… However different the holy causes people die for, they perhaps die basically for the same thing.

As an idea, this is a bitch slap to people who believe so strongly in a cause that they want everybody else to believe in it. That single-mindedness is the core question of Hoffer’s book: what kind of people become fanatics?

The answer is personal. And psychological. Before they believed, Hoffer writes in “The True Believer,” they felt small, confused, destined for nothing. With belief, they feel strong, certain. Their fanaticism transforms them; losers become winners. (“Faith in a holy cause is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in himself.”)

Lost people attaching themselves to a passing raft — if the cause sounds almost randomly chosen, it is. (“In pre-Hitlerian times, it was often a toss up whether a restless youth would join the Communists or the Nazis.”)

The movement’s goal doesn’t matter? Not according to Hoffer. He says: the more unrealistic and unattainable, the better. It’s not even important that the doctrine be understood. In fact, Hoffer says, the harder it is to believe, the better. Forget your mind, trust your heart, the zealot says, and his followers do just that. (“We can be absolutely certain only about things we don’t understand.”)

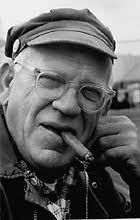

Who was Eric Hoffer (1902-1983)? Nobody’s ideal of a public intellectual. He barely saw the inside of a school. He spent most of his working life as a longshoreman on the San Francisco docks. Almost every day, he took a three-mile walk. Along the way, thoughts formed. Later they became sentences, then books. Over the years, he wrote ten. “The True Believer” is his masterpiece. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. To buy Tom Shachtman’s excellent biography, “American Iconoclast: The Life and Times of Eric Hoffer,” from Amazon, click here.]

You and I know that change is the one immutable law of life, that there are always at least two opinions, that we’ll probably die not knowing the ultimate answers. Not so the members of mass movements. They know it all. (“A mass movement…must act as if it had already read the book of the future to the last word. Its doctrine is proclaimed as a key to that book.”)

Textbook Hoffer: “A movement can exist without a God but no movement can exist without a devil.” How does a zealot come to power? At home and abroad, he finds devils to blame. And then damaged souls find him — and follow him.

BONUS VIDEOS