Books |

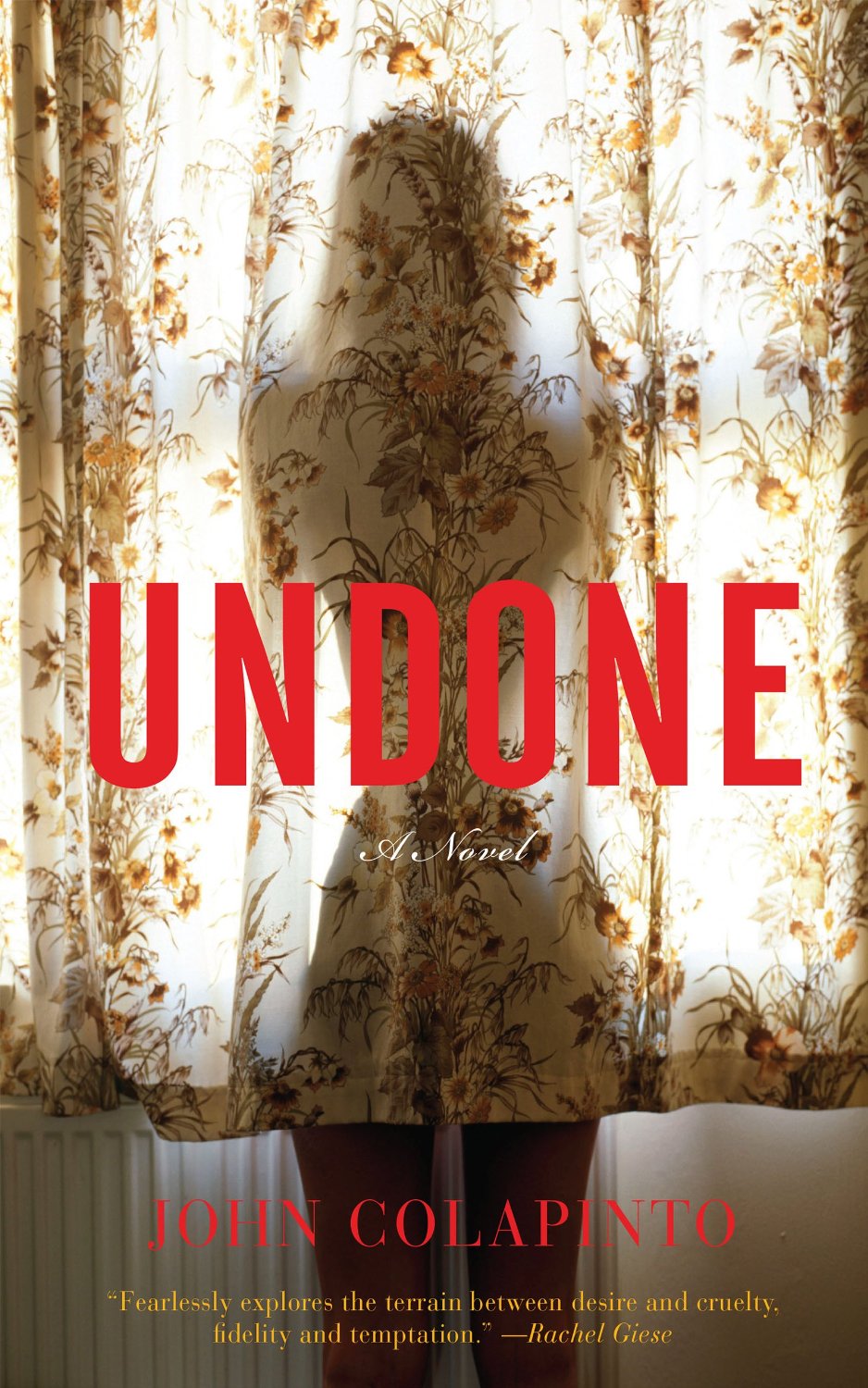

Undone

John Colapinto

By

Published: May 19, 2015

Category:

Fiction

UPDATE: This piece was published on Head Butler in May, 2015 — a New York publisher has made the book available. The Times ran a story — on April 10, 2016 — about the rejections from every other New York publisher. To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.

—-

File this under “Courage, lack of.” It’s John Colapinto’s story. It could have been mine. But after some of New York’s top publishers rejected “Married Sex” and I was seriously tempted to make it the fourth book published by Head Butler Books, the film rights were optioned by some of the smartest people in Hollywood and Open Road Media gave the novel an enthusiastic thumb’s up.

John Colapinto wasn’t so lucky. His latest novel, “Undone,” was published in Canada and Japan — but it was rejected by 41 publishers in this country and a similar number in the United Kingdom and Europe. And not because he was, like me, a first-time novelist with a book that ever so gently pressed the envelope. His last novel, “About the Author,” was loved here on Head Butler and elsewhere. He’s won a National Magazine Award. For a decade he’s been a staff writer at The New Yorker.

What went wrong?

Let John tell you.

The rejections were brimming with praise for everything about my book except the subject matter. In brief, it’s this: A good and decent man is tricked into thinking he sired a daughter 18 years earlier. This young woman is actually part of a conspiracy cooked up by her creepy boyfriend to seduce the man, then expose him on “Tovah in the Afternoon,” a daytime talk show. Nasty? Yes. But in a culture that has reality shows ruling entire channels, plausible.

The novel’s faux-incest theme and sprightly, often comic, tone made for a novel that US publishers deemed “a little too challenging.” Well, I built that challenging subject matter into the book, along with the unexpectedly jaunty tone with which I treated it. My intent wasn’t simply to shock. I’ve gotten a little bored with current fiction: smoothly professional, excellently crafted, exquisitely correct in terms of sexual politics.

You really do sense that the majority of authors today graduated at the top of their class at whatever Ivy League creative writing school they attended. But they don’t challenge or disturb me as “Portnoy’s Complaint” did when I was a teenager. Or “Couples.” Or “St. Urbain’s Horseman.” Or “Ginger Man.” Or many others I could name. So I took a tip from Kingsley Amis, who once said that when he wanted to read a novel, he sat down and wrote one — the kind of novel he wanted to read but could not find in the marketplace. Hence, “Undone.”

It’s not an immoral book. It’s not a dirty book. It is a slightly, uneasily, erotic book that treats of desire. And it does satirize the hypocrisy around our sexual Puritanism, which is matched only by the consumption of porn on our computers; the humorless and disapproving treatment of sex on our daytime talk shows, the sober denunciation of deviancy coupled with the lip-smacking sensationalism that accompanies “our next segment” on the latest scandal, whether it’s a politician’s anatomical selfies or a sitcom actress detailing the sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of her famous singer father. These all seem to be Zeitgeist topics not merely worthy of treatment in fiction, but crying out for it. And that’s why I spent five years writing “Undone.”

The book was the subject of a long, admiring feature story in Canada’s national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, that detailed the novel’s vexed publishing (non-publishing?) history; and it earned a rave review in the Toronto Star.

A separate review in the Globe was a little more circumspect, with the critic praising the novel’s “enthralling” narrative power, but worrying if the book was sufficiently literary, whether it had a properly serious message or moral in tow — or was it merely a genre page turner? (“When the writer deals in such volatile subject matter, you hope the writer’s got a damn good reason for it,” the critic opined.)

Well, it is a page-turner and it is (shockingly!) a comedy. Whether I had a good enough “reason” to treat such “volatile subject matter” is my secret, and is, in any case, up to readers to decide. But I will say that to treat of that subject matter with a solemn, evening-news-cast-sobriety of tone and the properly leaden pace of a “serious literary work” would be to fall into the very hypocrisy that the book satirizes.

We all love the latest sex scandal, we all gobble up the gossip about the indiscretions of our friends and neighbors and even family. Let’s not pretend otherwise. My book is thus written in a tone commensurate with the actual curiosity and delight we all feel about exploring these dark matters of the human psyche and soul. And though it was rejected by one American publisher for being “too entertaining for its subject matter,” it is the novel’s obvious entertainment elements (propulsive plot, frequent comedy) that make it, I would argue, the only serious way to treat this vexed and complicated subject.

Ironically — and wonderfully — the sole English-speaking country to take the book was Canada, my native land, the place I fled in 1989 for its perceived parochialism and its lack of cultural bravado so I could live and work in The United States of New York, that capitol of outspoken and fearless extroversion and artistic risk! In the wake of the press attention that my novel has received in Canada, it shot in a single day from an Amazon Canada ranking of 400,000 to 43, and landed in the #10 slot in literary fiction, one rank ahead of “The Goldfinch.”

At last report, Canada’s social fabric remains fully intact, a mood of wild erotic anarchy not unleashed. But of course it’s still early days. The book has only been out for a few weeks.

AN EXCERPT

Here are a few salient graphs from Part Two Chapter 1. They describe Dez — my Bad Guy — undergoing some experimental sex aversion therapy to try to cure of him of his taste in teenage girls. Dr Geld (“money” in German) is a sexologist quack.

After filling out the mountain of paperwork that absolved Dr. Geld of all legal liability, Dez had his chest and loins shaved, then hooked up to a set of electrodes. Geld sat, his delicately tapering fingers on a small switch. Dez was shown photographs and film clips of teenaged females and was administered electric shocks every time his humiliatingly exposed manhood betrayed him. At the end of three weeks of treatment, Geld pronounced himself “stunned” at the tenacity of Dez’s fixations — his erections seemed to be growing more powerful under the combined stimulus of the imagery and the electric jolts.“I cannot say that the prognosis is good,” Geld told him.

Dez, however, insisted that the treatment be continued and, over time, learned to counteract the imagery through a meditative technique that involved imagining scenes of sickness and torture as the teen beauties were projected before him. In time he achieved, through this act of “self-blinding,” the flaccidity Geld was seeking.When the doctor switched to showing him “therapeutically positive” images of age-appropriate women — female business executives climbing out of taxicabs in tight pencil skirts; an aproned mother bending at the waist to remove a well-browned turkey from the oven — Dez brought up from the storehouse of memory, and superimposed on the projected pictures, visions of adolescents bending in skirts to pick up tennis balls, or pale girls in private school uniforms

retrieving heavy books, on tippy-toe, from a high shelf. Thus did he induce the hearty erectile response his doctor was looking for.

Geld’s long, complicated paper on Dez’s case was published as a lead article in the New England Journal of Medicine and was covered by Time and Newsweek. In a Dateline TV documentary, Dez (shown in darkened silhouette and identified only as Patient X) was described as being among the world’s very rare examples of a successful sex aversion therapy, his case reviving the debate over whether it was, after all, possible to “cure” homosexuality (the Holy Grail of all sexological research in America). Dez’s name was duly removed from the state’s sex registry. He was, however, barred from working in any profession in which he had authority over young females. For instance, teaching.

But it so happened that Dez had always been drawn to pedagogy and the opportunities it offered for expanding the horizons of young people…