Books |

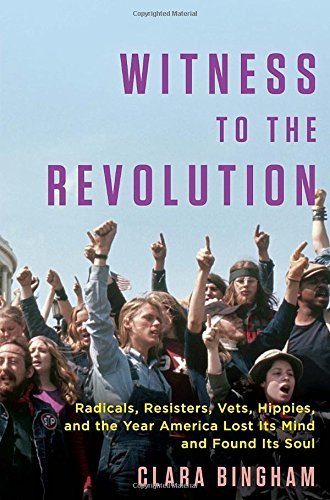

Witness to the Revolution: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year America Lost Its Mind and Found Its Soul

Clara Bingham

By

Published: Jul 31, 2016

Category:

History

Guest Butler Joe DePreta is a New York marketing executive and writer on cultural trends. He last wrote about Don Henley.

As the 1960s drew to a close, the United States was coming apart at the seams. The death toll in Viet Nam was approaching fifty thousand, and the ascendant counterculture was challenging nearly every aspect of American society – from work, family, and capitalism to sex, science, and gender relations.

Mass media had a tenuous relationship with America’s activism from 1969 to 1970. There was the daily chronicle of Vietnam in our living rooms. And then there was so much more that media was a blur that now gets lumped together in a “those were the days” vortex of surface scratching: Nixon and Kissinger’s surreptitious planning of the war’s escalation; My Lai; the moon landing; Woodstock; Altamont; racial tensions; Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers; the Manson murders; Kent State. And, like a loud undercurrent, there were Students for a Democratic Society, the Weather Underground, the Black Panthers, and the Chicago 8 trial in Chicago at odds which each other’s strategies.

Clara Bingham’s “Witness to the Revolution: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year America Lost Its Mind and Found Its Soul” is a chronological oral history of the most dramatic year of the 1960s. Bingham was born in 1963. But when she graduated from college in 1985, at “the height of the Reagan ’80s,” she started to think about the turbulent events that she only dimly sensed as a child. And she focused on the academic year of 1969-1970 as “a window through which to look at the whole decade of the ’60s.”

There’s always something seductive about oral history; at its best, it reads like a combination of a thriller and reality TV. Bingham, a journalist, author and documentary film producer whose work has focused on social justice and women’s issues, connects the dots in a way that reads like a thrilling novel. She’s captured the anger, commitment, confrontation, and idealism that made the period one of the most morally compelling in American history. [To read an excerpt, click here. To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Though I wasn’t old enough to get in the fray at the time, my empathy gene was in overdrive for many of the players –– and Bingham made me feel something for all of them. Consider:

Jan Barry, co-founder of Vietnam Veterans Against the War

I happened to be on the Syracuse University campus when the invasion of Cambodia took place (May 1, 1970). This university closes down. The students refuse to go to class. I was initially looking for student veterans and trying to have the conversation about war crimes testimony, and I discovered there were 500 student veterans on campus and they were outraged by what had happened at Kent State. A couple of these vets were turning a house they rented just off campus into a center for organizing vets. They made all kinds of phone calls, and they were going to have their own march. They had vets coming in from campuses across the whole of upstate New York, and they made it very clear that if any police or National Guard were going to come on campus, they were going to have to go through a line of vets.

Wayne Smith

Landing in Seattle, Washington, I went into the airport men’s room and there were all of these khaki uniforms bulging out of the trash bin, where people had taken off their uniforms and thrown them away as soon as they could. It was unbelievable. The uniform thing was big, not wanting people to know you were in the military. When I saw the uniforms in the men’s room trash bin, I was like, “Whoa . . . Welcome home!”

Daniel Ellsberg, describing his initial involvement in the Vietnam Moratorium, 1969

I was obviously giving up the chance to write memos to the president, and to Kissinger. I was with long-haired types from all over the world, and they were all pacifists, the lowest of the low. As the hours went by, I was handing out leaflets myself. I finally got enthusiastic about it. I would even go into the street and give leaflets to cars at the stoplight.”

Oral history begets oral history. So I called Clara Bingham:

Joe DePreta: Activism, from Students for a Democratic Society to the Weather Underground to the Black Panthers to Daniel Ellsberg, runs a consistent stream through the narrative. Given the parallels between then and now, has social media diluted “take it to the streets” activism?

Clara Bingham: Social media provides better reach. 600 underground newspapers took weeks to spread the word. Twitter, Facebook and trickle down buzz sort of replaces that sense of street community. But the sentiments are all there.

JDP: Other than the turbulent similarities of ‘69/’70 and now, what inspired you to write such an exhaustive oral history of the period?

CB: I started working on this book 5 years ago, before the Bernie Sanders movement took shape. My personal curiosity drove me. I grew up on the Upper West Side, and Central Park, my playground, was the New York staging area for the antiwar movement. Things have changed so much. There was more sacrifice then, more idealism. There also was a draft that affected 27 million men. Political issues were more personal and immediate. Now it’s just a lot of opinions.

JDP: It’s interesting that SDS leaders like Mark Rudd and David Harris speak a little apologetically about their actions, while Weathermen like Bernadine Dohrn and Bill Ayers do not. Why is that?

CB: Mark Rudd has been apologetic for years. He believes the Weathermen went too far and that they essentially killed SDS — they hurt the movement by playing right into Nixon’s hands. David Harris feels the same way. It became, ultimately, about their egos, which caused more factions and rivalries within the movement. Counter productive all the way around. Dorhn and Ayers, however, share the attitude “We’ll apologize when Kissinger apologizes.”

JDP: Hollywood has done an anemic job of dramatizing that era. In “The Big Chill,” the friends were all former activists at the University of Michigan. During a reunion dinner, Glenn Close’s character asks: “Was it all just fashion?” Any truth to that?

CB: Probably, since there was an undercurrent of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. I believe it’s telling that, in most of my interviews, I didn’t have one dry eye from Peter Coyote and John Perry Barlow to Daniel Ellsberg.

JDP: You make an interesting point that, as the anti war movement was gaining national traction, it was accompanied by rebellion in other forms including long hair, communes, free love, drug culture. This was a confrontational affront to an America clinging to an Eisenhower era simplicity and status quo. Does Bernie Sanders and his supporters represent that kind of affront now?

CB: Interesting point. Looking back, socially, the movement won. Politically, it lost. Bernie’s “revolution” is carrying on the unfinished business of the 60’s movement.

JDP: The book brings great clarity about the Chicago 8 trial. In retrospect, it’s horrifying that it didn’t outrage more Americans – Bobby Seale being bound and gagged in his courtroom chair, the beatings. Has our system changed dramatically since then?

CB: Yes! No one would be able to get away with what Judge Hoffman got away with. Today, it would be televised, and Hoffman’s actions would be seen as primitive, cartoon-like. On the other hand, the privatization of the prison system and the number of incarcerated black men is equally, if not more, criminal.

“Witness to the Revolution” is gripping, epic. Will you take a side? One way or another, you can’t help it.

—-

READER COMMENT: 1969 was the year I started college at UCLA and my mother encouraged me to get married so someone would take care of me. We closed down the university, but only on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, because on Tuesday and Thursday we went to the beach.

READER COMMENT #2: I was 19 in 1969. Your article and some of the excerpted material brought up a lot of emotion. I had escaped Vietnam by college deferment and then won the lottery (drew #354), but like many others of my age, I was a protestor, was pissed at my government, went to Woodstock and also became a bit paranoid! The picture from Kent State is seared into the brains of those of us who were of age at that time. Even now I cannot see it without a reaction of horror, disbelief and grief.