Books |

Gift Guide: A Child’s Holiday in America

By

Published: Dec 04, 2017

Category:

Children

Always on Christmas night there was music. An uncle played the fiddle, a cousin sang “Cherry Ripe,” and another uncle sang “Drake’s Drum.” It was very warm in the little house. Auntie Hannah, who had got on to the parsnip wine, sang a song about Bleeding Hearts and Death, and then another in which she said her heart was like a Bird’s Nest; and then everybody laughed again; and then I went to bed. Looking through my bedroom window, out into the moonlight and the unending smoke-colored snow, I could see the lights in the windows of all the other houses on our hill and hear the music rising from them up the long, steady falling night. I turned the gas down, I got into bed. I said some words to the close and holy darkness, and then I slept.

That’s Dylan Thomas, from “A Child’s Christmas in Wales.” It was like that in our country once upon a time, when families stuck together and houses passed from one generation to another. Now it’s hard to get the gang together without losing their attention to the private universes on the screens in their hands.

These books and videos have been road-tested on a child who’s never been shy about expressing her opinions. They passed muster. Some of them moved into heavy rotation. Now that she’s 15, they are nostalgic touchstones of her fast receding childhood. And how did that happen?

A note about these selections: They have the power to re-connect you to your childhood. Not the childhood you had, with its predictable dose of uncertainty and awkwardness, but the childhood you had in your head, the magic one. Reading and watching with a child, you can go there again. Here’s wishing you do.

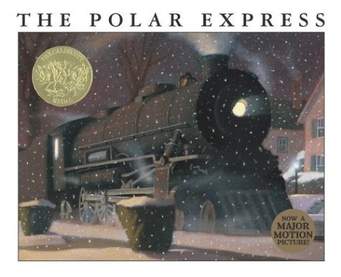

The Polar Express

The greatest Christmas book I’ve ever read begins on Christmas Eve, when a father tells his son there’s no Santa Claus. Later that night, a train packed with children stops in front of the boy’s house. He hops on and travels to the North Pole, where Santa offers him the first toy of Christmas. The boy chooses a reindeer’s bell. On the way home, he loses it. How he finds it and what that means — that’s where you reach for the Kleenex.

The theme of this book is belief. Not in Santa, though that will do just fine for kids. Belief in really big things, things we hope are true even in the face of all the information that says they are not. Chris Van Allsburg: “We can believe that extraordinary things can happen. We can believe fantastic things that might happen. Or we can believe that what we see is what we get. But if all that I believe in is what I can see, then the world is a smaller, less interesting place.”

So find a child. Settle in your chair. Start to read. Before you know it, your eyes will mist, you’ll be reaching for the Kleenex, and — and this is the best part of all, especially for the sophisticated and the hard of heart and the bitterly disappointed — you will believe.

The greatest Christmas video I’ve ever seen begins with a boy in rural England building a snowman. At midnight, as the boy looks out his window, the snowman lights up. The boy runs outside. He invites the snowman to tour his home. Then the snowman takes his hand. And off they fly, over England, over water, to the North Pole. The sequence is dazzling. The music is genius.

Santa gives the boy a scarf. The boy and the snowman fly home. As the boy is going inside, the snowman waves — a wave of goodbye. The boy rushes into his arms and hugs him. The next morning, the snowman’s just a few lumps of coal and an old hat.

Did that magical night really happen? The boy reaches into his pocket and finds the scarf. He drops to his knees and, almost as an offering, places it by the snowman’s hat. Gorgeous.

A few years ago, I decided our daughter was ready for a version of the Dickens classic not dumbed down by Disney. She lasted five minutes. I got the point: The text was too…texty. And I wasn’t the first to think that. Watch…

Books change over time, and over 170 years, “A Christmas Carol” has changed more than most. The evocation of Scrooge’s place of business is a slow starter. By our standards, the language is clotted and the piece is seriously overwritten. And it’s not like we haven’t seen Victorian London a zillion times in the movies or on TV.

After the non-start with our daughter, I began to work on the text. My goal wasn’t to rewrite Dickens, just to update the archaic language, trim the dialogue, cut the extraneous characters — to reduce the book to its essence, which is the story. (I think Dickens would approve. When he performed ‘A Christmas Carol’ — and he performed it 127 times — he used a trimmed-down version.) In the end, I did have to write a bit, but not, I hope, so you’ll notice; I think of my words as minor tailoring, like sewing on a missing button or patching a rip at the knee.

A book for 5-to-8-year-old children.

A book for 5-to-8-year-old children with no pictures.

Like this:

“Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” was an instant hit when it was published in America in 1964; its first printing sold out in a month. In the early l970s, Dahl produced a sequel, “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator.” Later, a movie with Gene Wilder — a very different movie from Tim Burton’s — turned Charlie into a kids’ classic. Starting around age 8 or 9, all the smart kids I’ve known have loved Dahl’s books and the drawings by Quentin Blake. “Matilda.” “James and the Giant Peach.” “The Fantastic Mr. Fox.” “The BFG.” They’re all here.

Shel Silverstein’s books are said to be for children 9 to 12. Nonsense. We started reading him when The Girl Who Hates To Read was six, and now we have the full collection. What is Silverstein’s appeal? Simple: He’s not full of the mealy-mouth bullshit that used to pass for children’s books. Starting way back in the ‘60s — when “Ozzie and Harriet” values were finally starting to wither and die everywhere but in kids’ books — he talked to kids with respect. He thought they were smart. And creative. And they needed to be encouraged, not sedated.

Here’s Silverstein’s message in 34 words: “Listen to the mustn’ts, child. Listen to the don’ts. Listen to the shouldn’ts, the impossibles, the won’ts. Listen to the never haves, then listen close to me… Anything can happen, child. Anything can be.”

“Polo” gives you an upbeat little dog in dark pants, a red jacket and a brown backpack. When we meet him, he’s just leaving his house — a giant tree on a tiny island. There’s a stake in the ground. And a rope tied to it and leading… somewhere. Polo unfurls his umbrella, steps up on the rope, and, like a circus performer, balances on it and walks over the ocean.

And so it goes, one zany adventure after another. And the illustrations! Vibrant primary colors make this a book of incessant good cheer. It’s a pleasure just to see “Polo” on a coffee table — the cover suggests the pleasure within.

“CDB!” has given generations of pre-schoolers a book they can “read” — like this:

R U C-P?

S, I M.

I M 2.

And the stories! In “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble,” a frightened donkey turns himself into a stone, but can’t reverse the process. In “Dr. De Soto,” a mouse who is an excellent animal dentist takes a huge chance and accepts a fox as a patient. in “The Real Thief,” a goose is false accused of stealing a royal ruby.

But even more, the moral and ethical sophistication in Steig’s books astonish me. In “Amos & Boris,” a mouse falls off his boat and contemplates death in terms never before seen in a kids’ book: “He began to wonder what it would be like to drown. Would it take very long? Would it feel just awful? Would his soul go to heaven? Would there be other mice there?”

Robert Sabuda is the king of pop-up books for kids. This is not the opinion of an adult who has pressed Sabuda’s books on his compliant kid. This is the opinion of just about every 4-to-8 year-old I know.

You can test this yourself. Put two pop-up books in front of a kid, one by Sabuda, one recommended by your neighborhood bookseller or librarian. Watch the kid choose the Sabuda, just about every time. Why? Because Sabuda’s books aren’t like anyone else’s pop-ups — in addition to selecting much-loved stories, telling them plainly and illustrating them colorfully, his pop-up pages are models of technology.

Consider his “Alice in Wonderland.” Open it, and a brilliant green forest leaps out at you. Turn the page. Now we have a house with arms and legs sticking out of windows and chimneys. Oh, but you missed something — how easily you made that transition.