Books |

Andre Dubus: A story about a murder

By

Published: Sep 21, 2021

Category:

Fiction

As he drops his kids off at his ex-wife’s house in winter, a father realizes that the condensation on the windows of his car is the warm breath of his children. That’s an Andre Dubus moment. A suburban street. People who have jobs, not careers. People you see in convenience stores and pizza joints and Target, but trust me on this — you don’t know them.

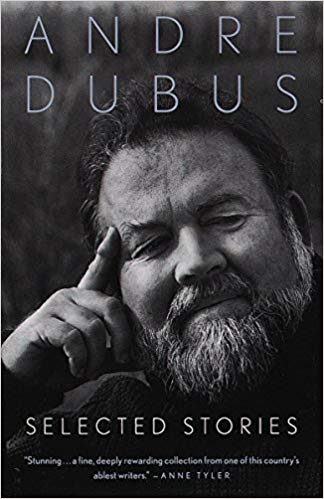

Andrew Dubus knew them. When I interviewed him in the early 1980s, he lived north of Boston, near the New Hampshire border, not near the ocean. He was a great, if not widely known writer, and the profile I wrote made that case, and the magazine put his picture on the cover, and he cried when he read it. That’s also a Dubus moment: “It gets down to what’s happening to you right now.”

What’s happening to me right now — and not just to me, but to many fathers of daughters, and many others — is boiling rage at Brian Laundrie, the 23-year-old who fought with his girlfriend, Gabby Petito, in Utah and then drove 2,400 miles home to Florida without her. Twenty-two days later, the Wyoming police found her remains. Not her body. Her remains.

If Brian Laundie did not kill Gabby Petito, he and his family are doing a terrific job making him look guilty. He drove away from his family’s house on September 14, knowing he was a “person of interest.” A day later, his parents spotted the car. On the third day, they drove it home. Only then did they call the police to report their son missing.

Plenty of blame around the edges of this story. The cops who responded to the fight in the Tetons believed Gabby’s bullshit story that she initiated the conflict, although that is a textbook response from an abused and scared woman. The Florida police completely missed Laundrie driving away.

And now we have, in the media, the typical debasement of language. Laundrie is hiding. He’s not “missing.” His parents are accomplices. The search was “called off.” Why? Yes, the search area is large. But also, technology and social media. Everyone with an iPhone is a deputy. This will end.

In one scenario, Laundrie kills himself. In another, he’s a suicide by cops. In a third, he’s apprehended, put on trial, and is sentenced to something less than life without parole. In a country now prone to absolute judgments about almost everything, that last outcome would be an outrage. But what if it played out like that? What if Gabby’s family lived in the same small town as Laundrie? What if her parents ran into him, day after day? What if that was intolerable? What if Gabby’s father had a trusted friend with a gun?

Todd Field’s film had a tiny budget ($1.6 million), and yet it attracted Sissy Spacek, Tom Wilkinson and Marisa Tomei. Half a dozen critics called it one of the decade’s best movies. At the Academy Awards, “In the Bedroom” was nominated for Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress and Best Adapted Screenplay. Marisa Tomei won for Best Supporting Actress.

Several critics noted that the movie won’t end for you when it ends. That’s equally true of the story. [To buy the paperback of “Selected Stories” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. To buy or stream the film from Amazon, click here.]

“KILLINGS”

On the August morning when Matt Fowler buried his youngest son, Frank, who had lived for twenty-one years, eight months, and four days, Matt’s older son, Steve, turned to him as the family left the grave and walked between their friends, and said: “I should kill him.” He was twenty-eight, his brown hair starting to thin in front where he used to have a cowlick. He bit his lower lip, wiped his eyes, then said it again. Ruth’s arm, linked with Matt’s, tightened; he looked at her. Beneath her eyes there was swelling from the three days she had suffered. At the limousine Matt stopped and looked back at the grave, the casket, and the Congregationalist minister who he thought had probably had a difficult job with the eulogy though he hadn’t seemed to, and the old funeral director who was saying something to the six young pallbearers. The grave was on a hill and overlooked the Merrimack, which he could not see from where he stood; he looked at the opposite bank, at the apple orchard with its symmetrically planted trees going up a hill.

Next day Steve drove with his wife back to Baltimore where he managed the branch office of a bank, and Cathleen, the middle child, drove with her husband back to Syracuse. They had left the grandchildren with friends. A month after the funeral Matt played poker at Willis Trottier’s because Ruth, who knew this was the second time he had been invited, told him to go, he couldn’t sit home with her for the rest of her life, she was all right. After the game Willis went outside to tell everyone goodnight and, when the others had driven away, he walked with Matt to his car. Willis was a short, silver-haired man who had opened a diner after World War II, his trade then mostly very early breakfast, which he cooked, and then lunch for the men who worked at the leather and shoe factories. He now owned a large restaurant.

“He walks the goddamn streets,” Matt said.

“I know. He was in my place last night, at the bar. With a girl.”

“I don’t see him. I’m in the store all the time. Ruth sees him. She sees him too much. She was at Sunnyhurst today getting cigarettes and aspirin, and there he was. She can’t even go out for cigarettes and aspirin. It’s killing her.”

“Come back in for a drink.”

Matt looked at his watch. Ruth would be asleep. He walked with Willis back into the house, pausing at the steps to look at the starlit sky. It was a cool summer night; he thought vaguely of the Red Sox, did not even know if they were at home tonight; since it happened he had not been able to think about any of the small pleasures he believed he had earned, as he had earned also what was shattered now forever: the quietly harried and quietly pleasurable days of fatherhood. They went inside. Willis’s wife, Martha, had gone to bed hours ago, in the rear of the large house which was rigged with burglar and fire alarms. They went downstairs to the game room: the television set suspended from the ceiling, the pool table, the poker table with beer cans, cards, chips, filled ashtrays, and the six chairs where Matt and his friends had sat, the friends picking up the old banter as though he had only been away on vacation; but he could see the affection and courtesy in their eyes. Willis went behind the bar and mixed them each a Scotch and soda; he stayed behind the bar and looked at Matt sitting on the stool.

“How often have you thought about it?” Willis said.

“Every day since he got out. I didn’t think about bail. I thought I wouldn’t have to worry about him for years. She sees him all the time. It makes her cry.”

“He was in my place a long time last night. He’ll be back.”

“Maybe he won’t.”

“The band. He likes the band.”

“What’s he doing now?”

“He’s tending bar up to Hampton Beach. For a friend. Ever notice even the worst bastard always has friends? He couldn’t get work in town. It’s just tourists and kids up to Hampton. Nobody knows him. If they do, they don’t care. They drink what he mixes.”

“Nobody tells me about him.”

“I hate him, Matt. My boys went to school with him. He was the same then. Know what he’ll do? Five at the most. Remember that woman about seven years ago? Shot her husband and dropped him off the bridge in the Merrimack with a hundred pound sack of cement and said all the way through it that nobody helped her. Know where she is now? She’s in Lawrence now, a secretary. And whoever helped her, where the hell is he?”

“I’ve got a .38 I’ve had for years. I take it to the store now. I tell Ruth it’s for the night deposits. I tell her things have changed: we got junkies here now too. Lots of people without jobs. She knows though.”

“What does she know?”

“She knows I started carrying it after the first time she saw him in town. She knows it’s in case I see him, and there’s some kind of a situation—”

He stopped, looked at Willis, and finished his drink. Willis mixed him another.

“What kind of a situation?”

“Where he did something to me. Where I could get away with it.”

“How does Ruth feel about that?”

“She doesn’t know.”

“You said she does, she’s got it figured out.”

He thought of her that afternoon: when she went into Sunnyhurst, Strout was waiting at the counter while the clerk bagged the things he had bought; she turned down an aisle and looked at soup cans until he left.

“Ruth would shoot him herself, if she thought she could hit him.”

“You got a permit?”

“I do. You could get a year for that.”

“Maybe I’ll get one. Or maybe I won’t. Maybe I’ll just stop bringing it to the store.”

Richard Strout was twenty-six years old, a high school athlete, football scholarship to the University of Massachusetts where he lasted for almost two semesters before quitting in advance of the final grades that would have forced him not to return. People then said: Dickie can do the work; he just doesn’t want to. He came home and did construction work for his father but refused his father’s offer to learn the business; his two older brothers had learned it, so that Strout and Sons trucks going about town, and signs on construction sites, now slashed wounds into Matt Fowler’s life. Then Richard married a young girl and became a bartender, his salary and tips augmented and perhaps sometimes matched by his father, who also posted his bond. So his friends, his enemies (he had those: fist fights or, more often, boys and then young men who had not fought him when they thought they should have), and those who simply knew him by face and name, had a series of images of him which they recalled when they heard of the killing: the high school running back, the young drunk in bars, the oblivious hard-hatted young man eating lunch at a counter, the bartender who could perhaps be called courteous but not more than that: as he tended bar, his dark eyes and dark, wide-jawed face appeared less sullen, near blank.

One night he beat Frank. Frank was living at home and waiting for September, for graduate school in economics, and working as a lifeguard at Salisbury Beach, where he met Mary Ann Strout, in her first month of separation. She spent most days at the beach with her two sons. Before ten o’clock one night Frank came home; he had driven to the hospital first, and he walked into the living room with stitches over his right eye and both lips bright and swollen.

“I’m all right,” he said, when Matt and Ruth stood up, and Matt turned off the television, letting Ruth get to him first: the tall, muscled but slender suntanned boy. Frank tried to smile at them but couldn’t because of his lips.

“It was her husband, wasn’t it?” Ruth said.

“Ex,” Frank said. “He dropped in.”

Matt gently held Frank’s jaw and turned his face to the light, looked at the stitches, the blood under the white of the eye, the bruised flesh.

“Press charges,” Matt said.

“No.”

“What’s to stop him from doing it again? Did you hit him at all? Enough so he won’t want to next time?

“I don’t think I touched him.”

“So what are you going to do?”

“Take karate,” Frank said, and tried again to smile.

“That’s not the problem,” Ruth said.

“You know you like her,” Frank said.

“I like a lot of people. What about the boys? Did they see it?”

“They were asleep.”

“Did you leave her alone with him?”

“He left first. She was yelling at him. I believe she had a skillet in her hand.”

“Oh for God’s sake,” Ruth said.

Matt had been dealing with that too: at the dinner table on evenings when Frank wasn’t home, was eating with Mary Ann; or, on the other nights—and Frank was with her every night—he talked with Ruth while they watched television, or lay in bed with the windows open and he smelled the night air and imagined, with both pride and muted sorrow, Frank in Mary Ann’s arms. Ruth didn’t like it because Mary Ann was in the process of divorce, because she had two children, because she was four years older than Frank, and finally—she told this in bed, where she had during all of their marriage told him of her deepest feelings: of love, of passion, of fears about one of the children, of pain Matt had caused her or she had caused him—she was against it because of what she had heard: that the marriage had gone bad early, and for most of it Richard and Mary Ann had both played around.

“That can’t be true,” Matt said. “Strout wouldn’t have stood for it.”

“Maybe he loves her.”

“He’s too hot-tempered. He couldn’t have taken that.”

But Matt knew Strout had taken it, for he had heard the stories too. He wondered who had told them to Ruth; and he felt vaguely annoyed and isolated: living with her for thirty-one years and still not knowing what she talked about with her friends. On these summer nights he did not so much argue with her as try to comfort her, but finally there was no difference between the two: she had concrete objections, which he tried to overcome. And in his attempt to do this, he neglected his own objections, which were the same as hers, so that as he spoke to her he felt as disembodied as he sometimes did in the store when he helped a man choose a blouse or dress or piece of costume jewelry for his wife.

“The divorce doesn’t mean anything,” he said. “She was young and maybe she liked his looks and then after a while she realized she was living with a bastard. I see it as a positive thing.”

“She’s not divorced yet.”

“It’s the same thing. Massachusetts has crazy laws, that’s all. Her age is no problem. What’s it matter when she was born? And that other business: even if it’s true, which it probably isn’t, it’s got nothing to do with Frank, it’s in the past. And the kids are no problem. She’s been married six years; she ought to have kids. Frank likes them. He plays with them. And he’s not going to marry her anyway, so it’s not a problem of money.”

“Then what’s he doing with her?”

“She probably loves him, Ruth. Girls always have. Why can’t we just leave it at that?”

“He got home at six o’clock Tuesday morning.”

“I didn’t know you knew. I’ve already talked to him about it.”

Which he had: since he believed almost nothing he told Ruth, he went to Frank with what he believed. The night before, he had followed Frank to the car after dinner.

“You wouldn’t make much of a burglar,” he said.

“How’s that?”

Matt was looking up at him; Frank was six feet tall, an inch and a half taller than Matt, who had been proud when Frank at seventeen outgrew him; he had only felt uncomfortable when he had to reprimand or caution him. He touched Frank’s bicep, thought of the young taut passionate body, believed he could sense the desire, and again he felt the pride and sorrow and envy too, not knowing whether he was envious of Frank or Mary Ann.

“When you came in yesterday morning, I woke up. One of these mornings your mother will. And I’m the one who’ll have to talk to her. She won’t interfere with you. Okay? I know it means—”

But he stopped, thinking: I know it means getting up and leaving that sun tanned girl and going sleepy to the car, I know—

“Okay,” Frank said, and touched Matt’s shoulder and got into the car.

There had been other talks, but the only long one was their first one: a night driving to Fenway Park, Matt having ordered the tickets so they could talk, and knowing when Frank said yes, he would go, that he knew the talk was coming too. It took them forty minutes to get to Boston, and they talked about Mary Ann until they joined the city traffic along the Charles River, blue in the late sun. Frank told him all the things that Matt would later pretend to believe when he told them to Ruth.

“It seems like a lot for a young guy to take on,” Matt finally said. “Sometimes it is. But she’s worth it.”

“Are you thinking about getting married?”

“We haven’t talked about it. She can’t for over a year. I’ve got school. I do like her,” Matt said.

He did. Some evenings, when the long summer sun was still low in the sky, Frank brought her home; they came into the house smelling of suntan lotion and the sea, and Matt gave them gin and tonics and started the charcoal in the backyard, and looked at Mary Ann in the lawn chair: long and very light brown hair (Matt thinking that twenty years ago she would have dyed it blonde), and the long brown legs he loved to look at; her face was pretty; she had probably never in her adult life gone unnoticed into a public place. It was in her wide brown eyes that she looked older than Frank; after a few drinks Matt thought what he saw in her eyes was something erotic, testament to the rumors about her; but he knew it wasn’t that, or all that: she had, very young, been through a sort of pain that his children, and he and Ruth, had been spared. In the moments of his recognizing that pain, he wanted to tenderly touch her hair, wanted with some gesture to give her solace and hope. And he would glance at Frank, and hope they would love each other, hope Frank would soothe that pain in her heart, take it from her eyes; and her divorce, her age, and her children did not matter at all. On the first two evenings she did not bring her boys, and then Ruth asked her to bring them next time. In bed that night Ruth said, “She hasn’t brought them because she’s embarrassed. She shouldn’t’ t feel embarrassed.”

Richard Strout shot Frank in front of the boys. They were sitting on the living room floor watching television, Frank sitting on the couch, and Mary Ann just returning from the kitchen with a tray of sandwiches. Strout came in the front door and shot Frank twice in the chest and once in the face with a 9 mm. automatic. Then he looked at the boys and Mary Ann, and went home to wait for the police.

It seemed to Matt that from the time Mary Ann called weeping to tell him until now; a Saturday night in September, sitting in the car with Willis, parked beside Strout’s car, waiting for the bar to close, that he had not so much moved through his life as wandered through it, his spirit like a dazed body bumping into furniture and corners. He had always been a fearful father: when his children were young, at the start of each summer he thought of them drowning in a pond or the sea, and he was relieved when he came home in the evenings and they were there; usually that relief was his only acknowledgment of his fear, which he never spoke of, and which he controlled within his heart. As he had when they were very young and all of them in turn, Cathleen too, were drawn to the high oak in the backyard, and had to climb it. Smiling, he watched them, imagining the fall: and he was poised to catch the small body before it hit the earth. Or his legs were poised; his hands were in his pockets or his arms were folded and, for the child looking down, he appeared relaxed and confident while his heart beat with the two words he wanted to call out but did not: Don’t fall. In winter he was less afraid: he made sure the ice would hold him before they skated, and he brought or sent them to places where they could sled without ending in the street. So he and his children had survived their childhood, and he only worried about them when he knew they were driving a long distance, and then he lost Frank in a way no father expected to lose his son, and he felt that all the fears he had borne while they were growing up, and all the grief he had been afraid of, had backed up like a huge wave and struck him on the beach and swept him out to sea. Each day he felt the same and when he was able to forget how he felt, when he was able to force himself not to feel that way, the eyes of his clerks and customers defeated him. He wished those eyes were oblivious, even cold; he felt he was withering in their tenderness. And beneath his listless wandering, every day in his soul he shot Richard Strout in the face; while Ruth, going about town on errands, kept seeing him. And at nights in bed she would hold Matt and cry or sometimes she was silent and Matt would touch her tightening arm, her clenched fist.

As his own right fist was now, squeezing the butt of the revolver, the last of the drinkers having left the bar, talking to each other, going to their separate cars which were in the lot in front of the bar, out of Matt’s vision. He heard their voices, their cars, and then the ocean again, across the street. The tide was in and sometimes it smacked the sea wall. Through the windshield he looked at the dark red side wall of the bar, and then to his left, past Willis, at Strout’s car, and through its windows he could see the now-emptied parking lot, the road, the sea wall. He could smell the sea.

The front door of the bar opened and closed again and Willis looked at Matt then at the corner of the building; when Strout came around it alone Matt got out of the car, giving up the hope he had kept all night (and for the past week) that Strout would come out with friends, and Willis would simply drive away; thinking: All right then. All right; and he went around the front of Willis’s car, and at Strout’s he stopped and aimed over the hood at Strout’s blue shirt ten feet away. Willis was aiming too, crouched on Matt’s left, his elbow resting on the hood.

“Mr. Fowler,” Strout said. He looked at each of them, and at the guns. “Mr. Trottier.”

Then Matt, watching the parking lot and the road, walked quickly between the car and the building and stood behind Strout. He took one leather glove from his pocket and put it on his left hand.

“Don’t talk. Unlock the front and back and get in.”

Strout unlocked the front door, reached in and unlocked the back, then got in, and Matt slid into the back seat, closed the door with his gloved hand, and touched Strout’s head once with the muzzle.

“It’s cocked. Drive to your house.”

When Strout looked over his shoulder to back the car, Matt aimed at his temple and did not look at his eyes.

“Drive slowly,” he said. “Don’t try to get stopped.”

They drove across the empty front lot and onto the road, Willis’s headlights shining into the car; then back through town, the sea wall on the left hiding the beach, though far out Matt could see the ocean; he uncocked the revolver; on the right were the places, most with their neon signs off, that did so much business in summer: the lounges and cafés and pizza houses, the street itself empty of traffic, the way he and Willis had known it would be when they decided to take Strout at the bar rather than knock on his door at two o’clock one morning and risk that one insomniac neighbor. Matt had not told Willis he was afraid he could not be alone with Strout for very long, smell his smells, feel the presence of his flesh, hear his voice, and then shoot him.

They left the beach town and then were on the high bridge over the channel: to the left the smacking curling white at the breakwater and beyond that the dark sea and the full moon, and down to his right the small fishing boats bobbing at anchor in the cove. When they left the bridge, the sea was blocked by abandoned beach cottages, and Matt’s left hand was sweating in the glove. Out here in the dark in the car he believed Ruth knew. Willis had come to his house at eleven and asked if he wanted a nightcap; Matt went to the bedroom for his wallet, put the gloves in one trouser pocket and the .38 in the other and went back to the living room, his hand in his pocket covering the bulge of the cool cylinder pressed against his fingers, the butt against his palm. When Ruth said goodnight she looked at his face, and he felt she could see in his eyes the gun, and the night he was going to. But he knew he couldn’t trust what he saw. Willis’s wife had taken her sleeping pill, which gave her eight hours—the reason, Willis had told Matt, he had the alarms installed, for nights when he was late at the restaurant—and when it was all done and Willis got home he would leave ice and a trace of Scotch and soda in two glasses in the game room and tell Martha in the morning that he had left the restaurant early and brought Matt home for a drink.

“He was making it with my wife.” Strout’s voice was careful, not pleading.

Matt pressed the muzzle against Strout’s head, pressed it harder than he wanted to, feeling through the gun Strout’s head flinching and moving forward; then he lowered the gun to his lap.

“Don’t talk,” he said.

Strout did not speak again. They turned west, drove past the Dairy Queen closed until spring, and the two lobster restaurants that faced each other and were crowded all summer and were now also closed, onto the short bridge crossing the tidal stream, and over the engine Matt could hear through his open window the water rushing inland under the bridge; looking to his left he saw its swift moonlit current going back into the marsh which, leaving the bridge, they entered: the salt marsh stretching out on both sides, the grass tall in patches but mostly low and leaning earthward as though windblown, a large dark rock sitting as though it rested on nothing but itself, and shallow pools reflecting the bright moon.

Beyond the marsh they drove through woods, Matt thinking now of the hole he and Willis had dug last Sunday afternoon after telling their wives they were going to Fenway Park. They listened to the game on a transistor radio, but heard none of it as they dug into the soft earth on the knoll they had chosen because elms and maples sheltered it. Already some leaves had fallen. When the hole was deep enough they covered it and the piled earth with dead branches, then cleaned their shoes and pants and went to a restaurant farther up in New Hampshire where they ate sandwiches and drank beer and watched the rest of the game on television. Looking at the back of Strout’s head he thought of Frank’s grave; he had not been back to it; but he would go before winter, and its second burial of snow.

He thought of Frank sitting on the couch and perhaps talking to the children as they watched television, imagined him feeling young and strong, still warmed from the sun at the beach, and feeling loved, hearing Mary Ann moving about in the kitchen, hearing her walking into the living room; maybe he looked up at her and maybe she said something, looking at him over the tray of sandwiches, smiling at him, saying something the way women do when they offer food as a gift, then the front door opening and this son of a bitch coming in and Frank seeing that he meant the gun in his hand, this son of a bitch and his gun the last person and thing Frank saw on earth.

When they drove into town the streets were nearly empty: a few slow cars, a policeman walking his beat past the darkened fronts of stores. Strout and Matt both glanced at him as they drove by. They were on the main street, and all the stoplights were blinking yellow. Willis and Matt had talked about that too: the lights changed at midnight, so there would be no place Strout had to stop and where he might try to run. Strout turned down the block where he lived and Willis’s headlights were no longer with Matt in the back seat. They had planned that too, had decided it was best for just the one car to go to the house, and again Matt had said nothing about his fear of being alone with Strout, especially in his house: a duplex, dark as all the houses on the street were, the street itself lit at the corner of each block. As Strout turned into the driveway Matt thought of the one insomniac neighbor, thought of some man or woman sitting alone in the dark living room, watching the all-night channel from Boston. When Strout stopped the car near the front of the house, Matt said: “Drive it to the back.”

He touched Strout’s head with the muzzle.

“You wouldn’t have it cocked, would you? For when I put on the brakes.”

Matt cocked it, and said: “It is now.”

Strout waited a moment; then he eased the car forward, the engine doing little more than idling, and as they approached the garage he gently braked. Matt opened the door, then took off the glove and put it in his pocket. He stepped out and shut the door with his hip and said: “All right.”

Strout looked at the gun, then got out, and Matt followed him across the grass, and as Strout unlocked the door Matt looked quickly at the row of small backyards on either side, and scattered tall trees, some evergreens, others not, and he thought of the red and yellow leaves on the trees over the hole, saw them falling soon, probably in two weeks, dropping slowly, covering. Strout stepped into the kitchen.

“Turn on the light.”

Strout reached to the wall switch, and in the light Matt looked at his wide back, the dark blue shirt, the white belt, the red plaid pants.

“‘Where’s your suitcase?”

“My suitcase?”

“Where is it.”

“In the bedroom closet.”

“That’s where we’re going then. When we get to a door you stop and turn on the light.”

They crossed the kitchen, Matt glancing at the sink and stove and refrigerator: no dishes in the sink or even the dish rack beside it, no grease splashings on the stove, the refrigerator door clean and white. He did not want to look at any more but he looked quickly at all he could see: in the living room magazines and newspapers in a wicker basket, clean ashtrays, a record player, the records shelved next to it, then down the hail where, near the bedroom door, hung a color photograph of Mary Ann and the two boys sitting on a lawn—there was no house in the picture—Mary Ann smiling at the camera or Strout or whoever held the camera, smiling as she had on Matt’s lawn this summer while he waited for the charcoal and they all talked and he looked at her brown legs and at Frank touching her arm, her shoulder, her hair; he moved down the hall with her smile in his mind, wondering: was that when they were both playing around and she was smiling like that at him and they were happy, even sometimes, making it worth it? He recalled her eyes, the pain in them, and he was conscious of the circles of love he was touching with the hand that held the revolver so tightly now as Strout stopped at the door at the end of the hall.

“There’s no wall switch.” “Where’s the light?”

“By the bed.”

“Let’s go.”

Matt stayed a pace behind, then Strout leaned over and the room was lighted: the bed, a double one, was neatly made; the ashtray on the bedside table clean, the bureau top dustless, and no photographs; probably so the girl—who was she?—would not have to see Mary Ann in the bedroom she believed was theirs. But because Matt was a father and a husband, though never an ex-husband, he knew (and did not want to know) that this bedroom had never been theirs alone. Strout turned around; Matt looked at his lips, his wide jaw, and thought of Frank’s doomed and fearful eyes looking up from the couch.

“Where’s Mr. Trottier?”

“He’s waiting. Pack clothes for warm weather.”

“What’s going on?”

“You’re jumping bail.”

“Mr. Fowler—”

He pointed the cocked revolver at Strout’s face. The barrel trembled but not much, not as much as he had expected. Strout went to the closet and got the suitcase from the floor and opened it on the bed. As he went to the bureau, he said: “He was making it with my wife. I’d go pick up my kids and he’d be there. Sometimes he spent the night. My boys told me.”

He did not look at Matt as he spoke. He opened the top drawer and Matt stepped closer so he could see Strout’s hands: underwear and socks, the socks rolled, the underwear folded and stacked. He took them back to the bed, arranged them neatly in the suitcase, then from the closet he was taking shirts and trousers and a jacket; he laid them on the bed and Matt followed him to the bathroom and watched from the door while he packed his shaving kit; watched in the bedroom as he folded and packed those things a person accumulated and that became part of him so that at times in the store Matt felt he was selling more than clothes.

“I wanted to try to get together with her again.” He was bent over the suitcase. “I couldn’t even talk to her. He was always with her. I’m going to jail for it; if I ever get out I’ll be an old man. Isn’t that enough?”

“You’re not going to jail.”

Strout closed the suitcase and faced Matt, looking at the gun. Matt went to his rear, so Stout was between him and the lighted hall; then using his handkerchief he turned off the lamp and said: “Let’s go.”

They went down the hall, Matt looking again at the photograph, and through the living room and kitchen, Matt turning off the lights and talking, frightened that he was talking, that he was telling this lie he had not planned: “It’ s the trial. We can’ t go through that, my wife and me. So you’ re leaving. We’ve got you a ticket, and a job. A friend of Mr. Trottier’s. Out west. My wife keeps seeing you. We can’t have that

anymore.”

Matt turned out the kitchen light and put the handkerchief in his pocket, and they went down the two brick steps and across the lawn. Stout put the suitcase on the floor of the back seat, then got into the front seat and Matt got in the back and put on his glove and shut the door.

“They’ll catch me. They’ll check passenger lists.”

“We didn’t use your name.”

“They’ll figure that out too. You think I wouldn’t have done it myself if it was that easy?”

He backed into the street, Matt looking down the gun barrel but not at the profiled face beyond it.

“You were alone,” Matt said. “We’ve got it worked out.”

“There’s no planes this time of night, Mr. Fowler.”

“Go back through town. Then north on I25.”

They came to the corner and turned, and now Willis’s headlights were in the car with Matt.

“Why north, Mr. Fowler?”

“Somebody’s going to keep you for a while. They’ll take you to the airport.” He uncocked the hammer and lowered the revolver to his lap and said wearily: “No more talking.”

As they drove back through town, Matt’s body sagged, going limp with his spirit and its new and false bond with Strout, the hope his lie had given Strout. He had grown up in this town whose streets had become places of apprehension and pain for Ruth as she drove and walked, doing what she had to do; and for him too, if only in his mind as he worked and chatted six days a week in his store; he wondered now if his lie would have worked, if sending Strout away would have been enough; but then he knew that just thinking of Strout in Montana or whatever place lay at the end of the lie he had told, thinking of him walking the streets there, loving a girl there (who was she?) would be enough to slowly rot the rest of his days. And Ruth’s. Again he was certain that she knew, that she was waiting for him.

They were in New Hampshire now, on the narrow highway, passing the shopping center at the state line, and then houses and small stores and sandwich shops. There were few cars on the road. After ten minutes he raised his trembling hand, touched Strout’s neck with the gun, and said: “Turn in up here. At the dirt road.”

Strout flicked on the indicator and slowed. “Mr. Fowler?”

“They’re waiting here.”

Strout turned very slowly, easing his neck away from the gun. In the moonlight the road was light brown, lighter and yellowed where the headlights shone; weeds and a few trees grew on either side of it, and ahead of them were the woods.

“There’s nothing back here, Mr. Fowler.”

“It’s for your car. You don’t think we’d leave it at the airport, do you?”

He watched Strout’s large, big-knuckled hands tighten on the wheel, saw Frank’s face that night: not the stitches and bruised eye and swollen lips, but his own hand gently touching Frank’s jaw turn turning his wounds to the light. They rounded a bend in the road and were out of sight of the highway: tall trees all around them now, hiding the moon. When they reached the abandoned gravel pit on the left, the bare flat earth and steep pale embankment behind it, and the black crowns of trees at its top, Matt said: “Stop here.”

Strout stopped but did not turn off the engine. Matt pressed the gun hard against his neck, and he straightened in the seat and looked in the rearview mirror, Matt’s eyes meeting his in the glass for an instant before looking at the hair at the end of the gun barrel.

“Turn it off.”

Strout did, then held the wheel with two hands, and looked in the mirror. “I’ll do twenty years, Mr. Fowler; at least. I’ll be forty-six years old.”

“That’s nine years younger than I am,” Matt said, and got out and took off the glove and kicked the door shut. He aimed at Strout’s ear and pulled back the hammer. Willis’s headlights were off and Matt heard him walking on the soft thin layer of dust, the hard earth beneath it. Strout opened the door, sat for a moment in the interior light, then stepped out onto the road. Now his face was pleading. Matt did not look at his eyes, but he could see it in the lips.

“Just get the suitcase. They’re right up the road.”

Willis was beside him now, to his left. Strout looked at both guns. Then he opened the back door, leaned in, and with a jerk brought the suitcase out. He was turning to face them when Matt said: “Just walk up the road. Just ahead.”

Strout turned to walk, the suitcase in his right hand, and Matt and Willis followed; as Strout cleared the front of his car he dropped the suitcase and, ducking, took one step that was the beginning of a sprint to his right. The gun kicked in Matt’s hand, and the explosion of the shot surrounded him, isolated him in a nimbus of sound that cut him off from all his time, all his history, isolated him standing absolutely still on the dirt road with the gun in his hand, looking down at Richard Strout squirming on his belly, kicking one leg behind him, pushing himself forward, toward the woods. Then Matt went to him and shot him once in the back of the head.

Driving south to Boston, wearing both gloves now, staying in the middle lane and looking often in the rearview mirror at Willis’s headlights, he relived the suitcase dropping, the quick dip and turn of Strout’s back, and the kick of the gun, the sound of the shot. When he walked to Strout, he still existed within the first shot, still trembled and breathed with it. The second shot and the burial seemed to be happening to someone else, someone he was watching. He and Willis each held an arm and pulled Strout face-down off the road and into the woods, his bouncing sliding belt white under the trees where it was so dark that when they stopped at the top of the knoll, panting and sweating, Matt could not see where Strout’s blue shirt ended and the earth began. They pulled off the branches then dragged Strout to the edge of the hole and went behind him and lifted his legs and pushed him in. They stood still for a moment. The woods were quiet save for their breathing, and Matt remembered hearing the movements of birds and small animals after the first shot. Or maybe he had not heard them. Willis went down to the road. Matt could see him clearly out on the tan dirt, could see the glint of Strout’s car and, beyond the road, the gravel pit. Willis came back up the knoll with the suitcase. He dropped it in the hole and took off his gloves and they went down to his car for the spades. They worked quietly. Sometimes they paused to listen to the woods. When they were finished Willis turned on his flashlight and they covered the earth with leaves and branches and then went down to a spot in front of the car, and while Matt held the light Willis crouched and sprinkled dust on the blood, backing up till he reached the grass and leaves, then he used leaves until they had worked up to the grave again. They did not stop. They walked around the grave and through the woods, using the light on the ground, looking up through the trees to where they ended at the lake. Neither of them spoke above the sounds of their heavy and clumsy strides through low brush and over fallen branches. Then they reached it: wide and dark, lapping softly at the bank, pine needles smooth under Matt’s feet, moonlight on the lake, a small island near its middle, with black, tall evergreens. He took out the gun and threw for the island: taking two steps back on the pine needles, striding with the throw and going to one knee as he followed through, looking up to see the dark shapeless object arcing downward, splashing.

They left Strout’s car in Boston, in front of an apartment building on Commonwealth Avenue. When they got back to town Willis drove slowly over the bridge and Matt threw the keys into the Merrimack. The sky was turning light. Willis let him out a block from his house, and walking home he listened for sounds from the houses he passed. They were quiet. A light was on in his living room. He turned it off and undressed in there, and went softly toward the bedroom; in the hail he smelled the smoke, and he stood in the bedroom doorway and looked at the orange of her cigarette in the dark. The curtains were closed. He went to the closet and put his shoes on the floor and felt for a hanger.

“Did you do it?” she said.

He went down the hall to the bathroom and in the dark he washed his hands and face. Then he went to her, lay on his back, and pulled the sheet up to his throat.

“Are you all right?” she said.

“I think so.”

Now she touched him, lying on her side, her hand on his belly, his thigh.

“Tell me,” she said.

He started from the beginning, in the parking lot at the bar; but soon with his eyes closed and Ruth petting him, he spoke of Strout’s house: the order, the woman presence, the picture on the wall.

“The way she was smiling,” he said.

“What about it?”

“I don’t know. Did you ever see Strout’s girl? When you saw him in town?”

“I wonder who she was.”

Then he thought: not was: is. Sleeping now she is his girl. He opened his eyes, then closed them again. There was more light beyond the curtains. With Ruth now he left Strout’s house and told again his lie to Strout, gave him again that hope that Strout must have for awhile believed, else he would have to believe only the gun pointed at him for the last two hours of his life. And with Ruth he saw again the dropping suitcase, the darting move to the right: and he told of the first shot, feeling her hand on him but his heart isolated still, beating on the road still in that explosion like thunder. He told her the rest, but the words had no images for him, he did not see himself doing what the words said he had done; he only saw himself on that road.

“We can’t tell the other kids,” she said. “It’ll hurt them, thinking he got away. But we mustn’t.”

She was holding him, wanting him, and he wished he could make love with her but he could not. He saw Frank and Mary Ann making love in her bed, their eyes closed, their bodies brown and smelling of the sea; the other girl was faceless, bodiless, but he felt her sleeping now; and he saw Frank and Strout, their faces alive; he saw red and yellow leaves failing to the earth, then snow: falling and freezing and falling; and holding Ruth, his cheek touching her breast, he shuddered with a sob that he kept silent in his heart.