Books |

Andy Warhol

By

Published: Feb 23, 2017

Category:

Art and Photography

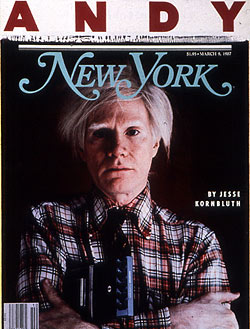

Andy Warhol died on February 22, 1987 — a Sunday morning, the best time for a media death. By Sunday night, I’d skimmed four books about Warhol and called the key sources to set up interviews for Monday. On Wednesday, I finished a 7,000 word cover story for New York magazine. The issue came out on Monday. On Tuesday, Tina Brown called to offer me a job at Vanity Fair, and a new chapter of my writing life began.

Andy had drawn shoes for Henri Bendel ads when Geraldine Stutz ran the store. In 1987, she was a publisher, full of tasty ideas. One was to collect those drawings from the 1950s, when Warhol was young and eager and unknown. Another was to have me write the text. She published this charming, whimsical art between covers of corrugated cardboard — on a coffee table, the book stood out. Thirty years after Andy Warhol’s death, it still looks witty and fresh. Or so says its author. [To buy “Pre-Pop Warhol” from Amazon, click here.]

The New York piece? Here’s the first section. For the rest, please click on the link at the bottom.

The first sign that there was something wrong with Andy Warhol, that he might be a mortal being after all, came three weeks ago. It was a Friday night, and after dinner with friends at Nippon, he was planning to see “Outrageous Fortune”, eat exactly three bites of a hot-fudge sundae at Serendipity, buy the newspapers, and go to bed. At dinner, though, he felt a pain. It was a sharp, bad pain, and rather than let anyone see him suffer, he excused himself. And as soon as he got home, the pain went away.

“I’m sorry I said I had to go home,” Warhol told Pat Hackett a few days later as he narrated his daily diary entry to her over the phone. “I should have gone to the movie, and no one would ever have known.”

In fact, no one remembered. And if anyone suspected trouble, it was dispelled the next week by Warhol’s ebullient spirits at the Valentine’s dinner for 30 friends that he held at Texarkana with Paige Powell, the young woman who was advertising director of Interview magazine by day and Warhol’s favorite date by night. Calvin Klein had sent him a dozen or so bottles of Obsession, and before Warhol set them out as party favors for the women, he drew hearts on them and signed his name. On one — for ballerina Heather Watts — he went further, inscribing the word the public never associates with Andy Warhol: “Love.”

The following afternoon, the pain returned. Brigid Berlin, his friend of 24 years, was with Warhol at his studio at 22 East 33rd Street. She was on her way to a London spa to lose weight, but she felt like one last chocolate binge. Warhol had a big box, so they went upstairs for one of the most familiar rituals of his life — someone acting out while he watched. “I’m dying for one,” he confessed. “But I can’t. I have a pain.”

Warhol spent most of that weekend in bed. On Monday, for the first time in six years, he didn’t go to work. That morning, he canceled his appointments with his exercise trainer for the entire week. On Tuesday, he still wasn’t well, so Paige Powell canceled a lunch for potential advertisers. That night, however, Warhol and Miles Davis were scheduled to model Koshin Satoh’s clothes at the Tunnel. And there was no way Andy Warhol could have tolerated an announcement that he was indisposed.

“Andy stood in a cold dressing room for hours, waiting to model,” says Stuart Pivar, a trustee of the New York Academy of Art and, for the past five years, Warhol’s best friend. “He was in terrible pain. You could see it in his face.” Still, Warhol went out and clowned his way through the show. Then he rushed backstage.

“Stuart, help. Get me out of here,” he gasped. “I feel like I’m gonna die.”

Warhol knew that the problem was his gallbladder, and that surgery was long overdue. But he had an even bigger problem with traditional medicine. In 1968, as he lay in the emergency room of a downtown hospital after Valerie Solanas had shot him, he heard doctors tell his friends there was no chance of his survival—an opinion they changed, he said, only when one friend announced that the patient was famous and had money. Ever since then, he feared doctors so much that when he went to auctions at Sotheby’s, he turned away to avoid even a look at New York Hospital. “If I go into a hospital again,” he confided to Beauregard Houston-Montgomery, “I won’t come out. I won’t survive another operation.”

But Warhol didn’t ignore his health—he just redirected his concern about it. He consulted nutritionists, popped vitamins at every meal, was treated with tinctures, and carried a crystal in his pocket. Two weeks ago, when the pain kept coming back, he visited one of these practitioners. “She manipulated the gallstones,” Warhol told a friend, “and they went into the wrong pipe.”

The pain didn’t go away, and Warhol finally agreed to surgery. Powell called him at home that Friday and asked him to come in and sign a copy of the new issue of Interview for Dionne Warwick. “I can’t right now,” he said. How about the ballet on Sunday? “Don’t cancel.”

That Saturday, surgeons at New York Hospital removed Warhol’s gallbladder. That night, he was awake and stable. At 5:30 on Sunday morning, however, he suffered a heart attack. Doctors worked for an hour, but Andy Warhol was right for the last time. He died, at 58, without regaining consciousness.

The news of Warhol’s death moved quickly through the city, and clusters of friends gathered to mourn. Many cried as if they’d lost a father. But as the eulogies came out, a more Warholian feeling began to overshadow this grief. It was unavoidable, really, and as the days passed, some of the people who knew him best began to say it: Andy would really have enjoyed this.

For the rest of the piece, click here.