Books |

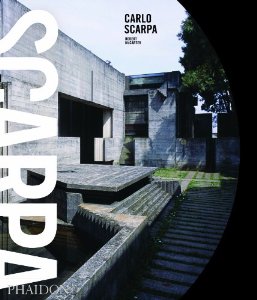

Carlo Scarpa

Robert McCarter

By

Published: May 10, 2022

Category:

Art and Photography

The Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906-1978) isn’t widely known. With good reason. Name a celebrated contemporary architect and you immediately think of his/her signature style. Scarpa’s work is harder to classify — he had no tricks he trotted out for every project. And you can’t name another architect who was also a gifted designer of blown glass.

I saw the Met exhibit, which was a wonder. Early in his career, Scarpa was affiliated with a glassblower in Murano. Not for him an expected Venetian prettiness; he explored all manner of textures and colors. (The New York Times slideshow will give you a sense of his range.)

The Times review of the glass exhibit was a rave — “If you are open to it, this exhibition can radically reshape your ideas about form, beauty, originality and art for art’s sake” — so I set out to educate myself about Scarpa. Happily, there is a book, rich in images, that presents a kind of biography by profiling 15 of his most important projects. For esthetes, it’s the answer to an extra-point question; for architects, I suspect it’s required reading. [To buy “Carlo Scarpa” from Amazon, click here.]

If there’s one idea that threads through Scarpa’s career, it’s the importance of looking hard. That began early for him; when he was two years old, his family moved to Vincenza, home of 21 buildings designed by the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. He played in those buildings and felt their power and authority; later, he respected those traditional, classical exteriors and reserved modernism for interiors.

Scarpa was a great admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, and he shared Wright’s interest in beams and joints, in different materials presented in juxtaposition. In 1951, Wright visited Venice. Many wanted to be his tour guide. Wright had no use for them. “Which one of you is Scarpa?” he demanded.

“I’d rather build museums than skyscrapers,” Scarpa said, and, in a sense, that’s all he did. In 1956, he was commissioned to design the Olivetti showroom in the most visible location in Venice, the Piazza San Marco. Best just to look at it:

The next year he began a 20-year project, the renovation of the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona. Scarpa knew the city well, and he drew on all the materials and surfaces that enriched its buildings. He created joints and slots that suggest medieval moats; the art is displayed so lovingly it holds the eye. Not a great video, but you’ll get the idea:

Scarpa’s masterpiece was the Brion Cemetary in a small town near Treviso. Here he draws on all the elements of his work: water, stone, reverence for history, a carefully expressed modernism. His philosophy of burial grounds is touching: “The place for the dead is a garden. I wanted to show some ways in which you could approach death in a social and civic way; and further what meaning there was in death, in the ephemerality of life other than these shoe-boxes.”

Scarpa does something here I’ve never seen elsewhere. In the open-air family tomb, he tilts the tombs of the husband and wife so they lean toward one another — in death they are as they were in life.

On a trip to Japan, Scarpa fell from a roof — it’s said he was leaning over the edge to get a better view — and died. He’s buried in an obscure corner of the Brion Cemetery. And he’s buried standing up, wrapped in linen. Original to the end, and forever after.