Books |

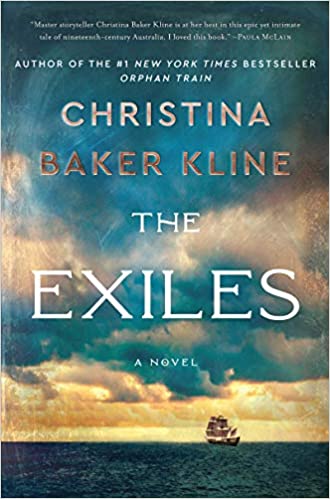

Christina Baker Kline: The Exiles

By

Published: Oct 20, 2020

Category:

Fiction

Her first four novels had modest sales, so Christina Baker Kline’s publisher decided to bring out her fifth as a paperback original. Book clubs discovered it, loved it, and members shared it with friends. “Orphan Train” became the sleeper hit of 2013. It spent 105 weeks on the New York Times list, more than a year in the top 10, and five weeks at #1 — it outsold Grisham. Its success had less to do with packaging than with its subject: the hidden-in plain-sight, early 20th century story of poor immigrant children in east coast cities who were sent thousands of miles away to be farm laborers. The themes — female courage and resilience — resonated powerfully with female readers. [To buy “Orphan Train” from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Baker’s next novel, “A Piece of the World,” was inspired by “Christina’s World,” Andrew Wyeth’s 1948 painting, on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Anna Christina Olson (1893 -1968) is the woman in the painting. She suffered from a degenerative muscular disorder that made walking impossible. But she refused to use a wheelchair. She crawled. Over the years, Wyeth made 300 pictures at her house in Maine, but it was the image of her crawling to pick blueberries that inspired this painting. Once again, a disadvantaged woman turns out be strong and courageous. [To read my review and buy the book from Amazon, click here.]

And now we have “The Exiles,” which is about lowest class women in the 19th century in England who were exiled to Australia, never to return. What about the brave men heroically taming a new frontier? What about the hardened convicts who created successful lives in a distant colony? Not here. We get plucky British women, mistreated Aboriginal women, women who triumph over caste prejudice. The novel fills 370 pages — well over my preferred length — but it starts fast and never falters. Here, read an early chapter.

After I read that, I kept going. The church bell tolled an ungodly hour. I pressed on, fighting the urge to skim. I could never see ahead. I was constantly surprised. A miniseries? On the way! [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

One reason “The Exiles” is so excellent is because Kline is my favorite kind of historical novelist — she does a ton of research, completely absorbs it, and never shows her work. And what work!

While researching “The Exiles,” I visited the People’s Palace and Winter Gardens in Glasgow, Newgate Prison in London, and the English village of Tunbridge Wells; I went to Australia twice and explored the Cascades Female Factory in Tasmania (now a museum), the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, a manor house called Runnymede, the Hobart Convict Penitentiary, the Richmond Gaol Historic Site, the Maritime Museum of Tasmania, and many other convict sites, museums, and libraries in Sydney and Melbourne. I read dozens of books, articles, and essays about convict life and Tasmanian Aboriginal history. To get a sense of the vocabulary and attitudes of the time, I read novels, nonfiction books, newspapers, and journals written in the mid-19th century. I became obsessed with arcane details, some of which I discovered after finishing a draft or two. For example, after I’d handed in the manuscript I read about the inexpensive tallow made of animal fat used for candles in prisons and the homes of the poor. It smelled terrible and dripped copiously. I went back and wove that detail in.

The reader learns by seeing. The provisions the sailors received: beef, rum, oatmeal, butter, cheese. “Sometimes — rarely — the women would get a taste of their rations.” Women’s work on the ship to Australia: coiling sodden rope, scrubbing the deck with stones and sand, cleaning privies “with a mix of lime and calcium chloride that made their noses burn and eyes water.” To remove the taste of salt from their lips, they rubbed them with lard and whale oil.

And yet. “The sheltered, unworldly governess who’d entered the gates of Newgate was gone, and in her place was someone new. She barely recognized herself. She felt as flinty as an arrowhead. As strong as stone.”

This is not “women’s fiction” as we used to know it.