Books |

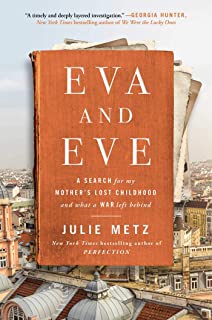

Eva and Eve: A Search for My Mother’s Lost Childhood and What a War Left Behind

Eve Metz

By

Published: Apr 06, 2021

Category:

Memoir

Julie Metz can do anything. She’s a sought-after designer; the cover she created for my first novel was light years better than the one the publisher forced on me. She wrote a memoir, Perfection, that began as a horror story, turned into a tale of revenge, ended in hard-won sanity. (The headline of the Times piece about the book pulls no punches: One Dead Husband and Five Other Women.) And now she’s written a book about her mother that starts in curiosity, turns into a detective story, and ends in deep understanding.

Julie Metz’s parents were the art directors of Simon & Schuster. For three decades. That’s not just a long run, it’s a record. Eve Metz came home with stories — publishing stories. She rarely shared any stories about her childhood in Vienna and her family’s escape from Nazi Europe. Her daughter thought she’d heard everything there was to know, or at least what she remembered. Eve Metz as a secret keeper? Beyond unlikely.

Eve Metz died in 2006. She left behind a keepsake book hidden in the back of a drawer. A Poesie Album. “Something lots of girls in Europe kept. The closest thing we would have is an autograph album. Friends and relatives copied out a short poem, drew pictures, or pasted in cut out art. She had never shared this keepsake book with anyone, not even my father in their fifty year marriage. When my father and I looked through it the first time, we both knew that many of the people who signed the book, who didn’t get out of Vienna by March 1940, could not have survived the anti-Semitic genocide that was well underway. It was too late to ask my mother about this book and the childhood friends she never saw again after she left Vienna, but I couldn’t let go of the strong desire to know more.”

A clue: In her Poesie Album, her mother was called Eva. When she became an American citizen, she was Eve. “For my mother there was a Before and an After: the sheltered childhood in Vienna, the savagery and terror of two years trying to escape and then the flight to America. The only way forward was to leave the child behind her and make a new life as an immigrant with a new name.”

In 2012, Julie Metz visited Vienna. She couldn’t get into the apartment building where her mother had lived, so she took a photo of the address list on the outside, noting that one occupant was a film producer. She sent him an email, asking if she could visit the interior of the building the next time she was in Vienna.

Four years later, I got an out-of-the-blue email from Franz Novotny, owner of the film business. An event was happening at the building, the installation of a Stolpersteine (“stumblestone”) plaque outside the building to honor a former inhabitant of the building who had been deported to Dachau and murdered in April 1938. The announcement of the event jogged his memory, and he emailed because he thought I might be related to Jakob Ehrlich. I wrote back to tell him that I was not related to Ehrlich but my mother had grown up in the building and her father had run a paper goods factory in the rear courtyard. Franz wrote back to tell me that his film company was located in my grandfather’s former printing factory. From thousands of miles away I could hear the door to Number 22 Weimarer Strasse open wide.

In one of her mother’s stories, her father’s life was saved because of a piece of paper packaging produced in his factory. And that led to a second unlikely event: the approval of her mother’s exit visa. I’ve read my share of books and seen my share of movies about escapes from the Nazis; I’m hard to surprise. These two stories made me blink in wonderment. And there were others. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For the audiobook, click here.]

And in the end, what did Julie Metz learn?

Her life, and therefore mine, hung on such a slim thread of good fortune, one that was denied to so many equally worthy people deported to extermination camps. The luck of my family’s survival depended on the generosity or intervention of people I could never know: the employees at my grandfather’s printing factory, who produced an item of paper packaging vital to the Third Reich war effort; relatives in the United States who vouched for the Singer family and helped with the cost of boat tickets to America; a mysterious vice-consul at the United States consulate in Vienna who granted a visa; and perhaps even some Nazi officials who were open to negotiation or bribery.

Luck. The hand of God. Random acts of kindness. And unexpected goodness, from people who didn’t have to help but did. And thus a book that speaks very much to the present moment:

My mother’s keepsake book felt like a challenge, as if she were asking me to tell our family’s story to those people of her adopted country, people who may have forgotten that we are a nation of both adventurers and reluctant refugees, and that there could be quiet greatness in following one woman’s journey from one name to another — from Eva to Eve.

This is a book about a girl who didn’t become a statistic in 1940 and had a fulfilling second life. Yes, and also a book with a message for us in 2021.