Books |

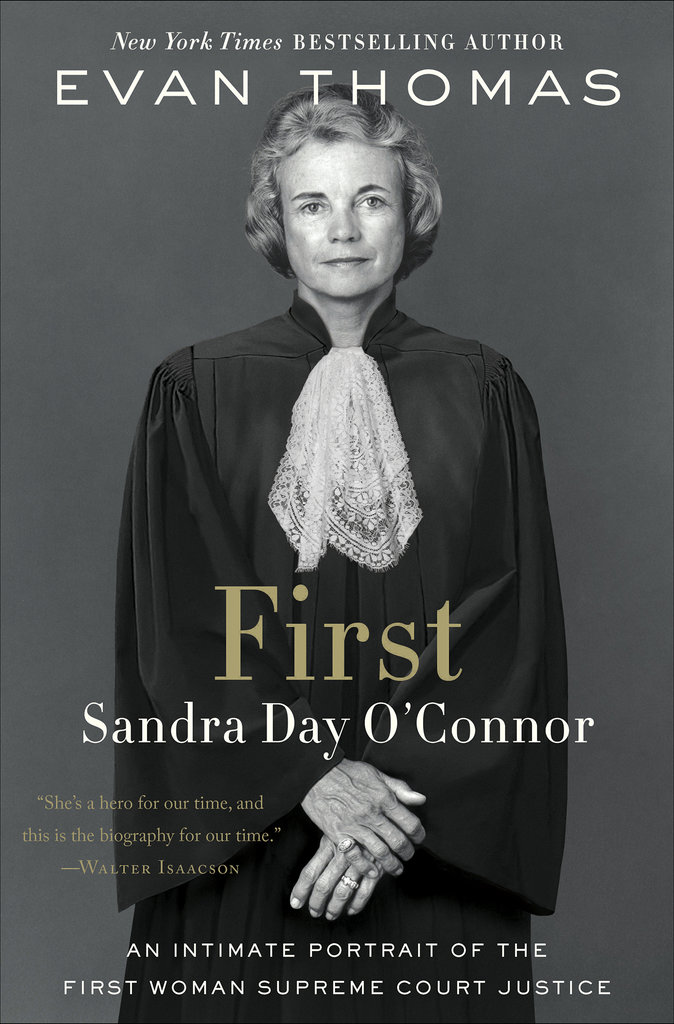

First: Sandra Day O’Connor

Evan Thomas

By

Published: Apr 09, 2019

Category:

Biography

GUEST BUTLER JILL SWITZER has been a member of the State Bar of California for 40 years and now is a full-time mediator. She writes a weekly column for Above the Law, where she rants without interruption. She also contributes to Legal Ink and other legal publications.

Sandra Day O’Connor’s life and career is a Rubik’s Cube. As Evan Thomas describes her in “First,” she has many facets: cowgirl, rancher, lawyer, wife, mother of three, legislator, state court judge — and the first female Supreme Court Justice. Everyone who reads this biography will have a different perspective, whether lawyer or not.

For me, I flash back to 1981. I was a baby lawyer, practicing for less than five years, when President Reagan fulfilled a campaign promise to put a woman on the United States Supreme Court by nominating Judge Sandra Day O’Connor. Who? Very few knew who she was, but that changed fast. Starting with women lawyers. We were thrilled and delighted — at long last there was recognition that a woman could be and should be on the high court. It had been a long slog for us to gain any kind of parity with male lawyers (still a work in progress). For women lawyers combating bias in the courtroom (as one male lawyer told me, “Women don’t make good trial lawyers”), the boardroom, law firms, and elsewhere, Justice O’Connor’s confirmation was full of promise for all of us.

Thomas’s biography begins at the beginning: Justice O’Connor’s childhood and adolescence growing up on a ranch in a remote part of Arizona, where the values were grit, self-reliance, determination, and perseverance. As Thomas writes:

Sandra Day was born on March 26, 1930, in the city of El Paso, Texas, the only city close enough—four hours by train—to have a proper hospital. The Arizona ranch house to which she was brought a couple of weeks later, after the two-hundred-mile trip, was a square, four-room adobe structure. Known as Headquarters, it stood eight miles from the main road. Visitors were announced by the cloud of dust they raised. The house had no running water, indoor plumbing, or electricity. Coal gas lamps lit the rooms; the bathroom was a wooden privy 75 yards downwind from the house. Harry and Ada Mae Day and their baby daughter, Sandra, slept in the house; the ranch’s four or five cowboys slept on the screened porch. Flies were everywhere. On still summer nights, when it was too hot to sleep, Sandra’s parents soaked her bedsheets in cool water. “It was no country for sissies,” O’Connor recalled. “We saw a lot of life and death there.”

She couldn’t get a job as a lawyer when she graduated from Stanford law school (not the same fate that befell her classmate, William Rehnquist, her eventual colleague on the Supreme Court). She volunteered at a government law office until she returned to Arizona, having married John O’Connor, a Stanford classmate.

Just as in California, no one would hire her — her husband, in contrast, was welcomed into a Phoenix law firm — so she opened up her own office, which led to stints in the Arizona legislature and the Arizona bench. Except for that last giant step, her career has mirrored the careers of many women lawyers who, unable to get hired by law firms, have forged their own paths in private practice, government and the judiciary. It’s a familiar yet compelling story. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Thomas describes in detail the Justice’s years on the court, the friendships forged, the collaborations made and unraveled, and her constant belief that civility was paramount, even in vivid disagreement. Whether you agree or not with Justice O’Connor’s jurisprudence (and I leave that for constitutional scholars to hash out), she knew that the country was watching her every opinion.

It’s fascinating to read about her decision-making process. While she wanted to follow stare decisis (precedent), she also asked the question “Is it fair?” The late Justice Antonin Scalia thought that question irrelevant to his belief in originalism; for him, the Constitution means what it says at the time it was drafted and no more. O’Connor drove him nuts, and he was never bashful about expressing his consternation at some of her opinions.

“First” is a fascinating look at how she crafted her decisions, how she worked for consensus with the other Justices, and how even the most ornery of them, Clarence Thomas, came to appreciate her collegiality and her willingness to bridge philosophical differences by breaking bread together at the weekly luncheon. Justice O’Connor’s theory was pure folk wisdom: you catch more flies with honey than with vinegar. Civility was paramount for her in her interactions with colleagues and clerks, and in her opinions. More than once she redlined language that she thought was too snarky, too over the top.

“First” is also the love story between Sandra Day and John O’Connor from the time of their marriage in the 1950s to his death from Alzheimer’s in 2009. Justice O’Connor recognized the career sacrifices her “trailing spouse” husband had made in following her to Washington. That sacrifice was a big factor in her decision to step down from the Court in January 2006 to care for her ailing husband. One sacrifice begets another. The irony is that while Justice O’Connor took her husband home to Phoenix to care for him, she discovered after just six months she could no longer do so and placed him where he could get the care he needed, taking him away from her for good.

Not one to disappear into retirement, Justice O’Connor started an e-learning program for students who have had no civics education and no understanding of the rights and responsibilities of the three branches of government. She didn’t stop working on the project and other activities until her own diagnosis of Alzheimer’s forced her from public view.

Justice O’Connor’s life and career are a story of quiet stoicism (her battle with breast cancer in the late 1980s did not slow her down; ten days after her surgery she was back on the bench), fidelity to her values and dedication to her family. Am I a fan? Absolutely. Sandra Day O’Connor made it easier, at least a little bit, for every woman lawyer — in fact, for every woman — to strive for professional achievement and recognition. For that alone, we women lawyers will be forever in her debt.

—–

To read an excerpt from “First,” click here.