Books |

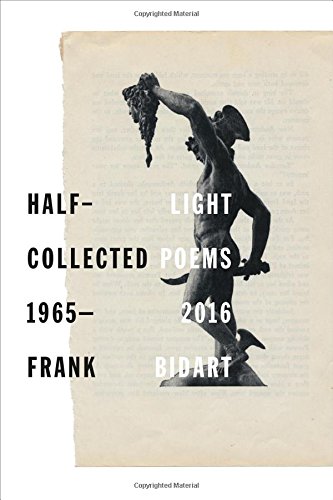

Frank Bidart: Half-light: Collected Poems 1965-2016

By

Published: Jan 29, 2018

Category:

Poetry

Eight books, collected in one. 736 pages in a beautifully produced hardcover. Half a century of poetry.

Frank Bidart is the 2017 winner of the National Book Award for Poetry, the 2007 winner of Yale’s Bollingen Prize in American Poetry, a three-time finalist for the Pulitzer in poetry — and that’s just the start of the praise that is regularly heaped on his work.

If you’re a constant reader of poetry, Bidart’s name and poems are familiar to you. If not, prepare to be stunned. Bidart comes out of the prose-like, personal/ confessional school of Robert Lowell — he’s co-editor of the “Collected Poems of Robert Lowell“ — and the candor is stunning. So is the look of the poems: As Hilton Als noted in The New Yorker:

…he capitalizes individual words that underscore what was stressed in the preceding line, or he cuts a statement of fact in half, letting it float into the white space of doubt, even as other voices are introduced — voices that are separate from but inseparable from the author’s “I.”

Bidart has explained that “the only way I can sufficiently . . . express the relative weight and importance of the parts of a sentence—so that the reader knows where he or she is and the ‘weight’ the speaker is placing on the various elements that are being laid out—is [through] punctuation. . . Punctuation allows me to ‘lay out’ the bones of a sentence visually, spatially, so that the reader can see the pauses, emphases, urgencies and languors in the voice.”

So this, from a poem called “Queer,” is a common Bidart layout:

Lie to yourself about this and you will

forever lie about everything.

Everybody already knows everything

so you can

lie to them. That’s what they want.

But lie to yourself, what you will

lose is yourself. Then you

turn into them.

For each gay kid whose adolescence

was America in the forties or fifties

the primary, the crucial

scenario

forever is coming out—

or not. Or not. Or not. Or not. Or not.

That poem is a good way to consider Bidart’s concerns: guilt, longing, love vs. touch. Yes, he’s Catholic. Gay. From Bakersfield, California, a home he was eager to leave, even if he didn’t quite know what he was doing as a graduate student in English at Harvard. I knew him slightly there. He seemed shy but determined, rueful yet hungry — combinations that are eminently likeable. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Bidart is a master of dramatic monologues. His characters are troubled, contradictory, relentless. Here’s the start of Ellen West, a poem about an anorexic:

I love sweets,—

heaven

would be dying on a bed of vanilla ice cream …

But my true self

is thin, all profile

and effortless gestures, the sort of blond

elegant girl whose

body is the image of her soul.

—My doctors tell me I must give up

this ideal;

but I

WILL NOT … cannot.

Only to my husband I’m not simply a “case.”

But he is a fool. He married

meat, and thought it was a wife.

Herbert White is a killer and a pervert:

When I hit her on the head, it was good,

and then I did it to her a couple of times,—

but it was funny,

— afterwards,

it was as if somebody else did it…

Everything flat, without sharpness, richness or line.

Still, I liked to drive past the woods where she lay,

tell the old lady and the kids I had to take a piss,

hop out and do it to her…

The whole buggy of them waiting for me

made me feel good;

but still, just like I knew all along,

she didn’t move.

When the body got too discomposed,

I’d just jack off, letting it fall on her…

—It sounds crazy, but I tell you

sometimes it was beautiful—; I don’t know how

to say it, but for a minute, everything was possible—;

and then,

then,—

well, like I said, she didn’t move: and I saw,

under me, a little girl was just lying there in the mud:

and I knew I couldn’t have done that,—

somebody else had to have done that,—

standing above her there,

in those ordinary, shitty leaves…

He’s just as strong in what might, in others, be called narrative poetry, as in Golden State, about his father:

To see my father

lying in pink velvet, a rosary

twined around his hands, rouged,

lipsticked, his skin marble …

My mother said, “He looks the way he did

thirty years ago, the day we got married,—

I’m glad I went;

I was afraid: now I can remember him

like that …”

Ruth, your last girlfriend, who wouldn’t sleep with you

or marry, because you wanted her

to pay half the expenses, and “His drinking

almost drove me crazy—”

Ruth once saw you

staring into a mirror,

in your ubiquitous kerchief and cowboy hat,

say:

“Why can’t I look like a cowboy?”

You left a bag of money; and were

the unhappiest man

I have ever known well.

I could on quoting Bidart all day. But that would be dishonest. Many of these poems read like short stories that Denis Johnson might have written. Others invoke classical themes, philosophy, history. You can trick yourself into thinking you can gulp this book, that it’s a pageturner. It’s anything but. I’ve been reading this book for weeks, and I put it down often. I’ll be thinking about it and returning to it for years.

BONUS VIDEO

Frank Bidart reads Lowell’s “For the Union Dead”