Books |

Great? Or snobbish? You make the call.

By

Published: Mar 01, 2018

Category:

Art and Photography

A new friend and I were walking, and the conversation turned to Venice, and because I had a few tidbits still accessible in my fading memory, I mentioned Carlo Scarpa. Time stopped. She was the world expert on Scarpa. We traded stories, and then she took me deeper, and in that exchange, a friendship was sealed.

Carlo Scarpa? Yes. Esoteric. So what? Only in 2018 aging white male Red State America is it considered smart to know nothing. Among people who can read without moving their lips, knowing stuff is cool.

Are these books snobbish, fit only for annoying your friends at parties? Or are they brain food? You make the call.

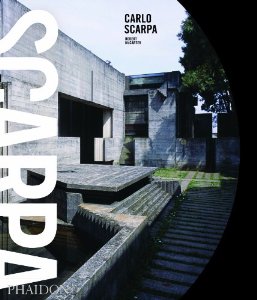

Carlo Scarpa

Name a celebrated contemporary architect and you immediately think of his/her signature style. Scarpa’s work is harder to classify — he had no tricks he trotted out for every project. And you can’t name another architect who was also a gifted designer of blown glass. Scarpa was a great admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, and he shared Wright’s interest in beams and joints, in different materials presented in juxtaposition. In 1951, Wright visited Venice. Many wanted to be his tour guide. Wright had no use for them. “Which one of you is Scarpa?” he demanded.

A Village Lost and Found: Scenes in Our Village

Brian May was the lead guitarist for Queen. (“We Will Rock You”) When Queen quieted down, Brian May completed his academic work and earned a PhD. from Imperial College, London. (You can buy his thesis on Interplantary Dust, A Survey of Radial Velocities in the Zodiacal Dust Cloud.) As a mass communicator, he had an interest in a more direct explanation of the way things work, so he co-authored a book, “Bang! The Complete History of the Universe.” And now the versatile Dr. May has topped himself — he’s taken a lifelong interest in stereoscopic photography and produced a picture-and-text book that is at once a historical chronicle and a work of art. “A Village Lost and Found: Scenes in Our Village” comes in a slipcase; in a separate folder, you get a 3-D viewer that May created for this project.

Dieter Rams: As Little Design as Possible

Dieter Rams is the German designer whose work for Braun is clearly the inspiration for Apple’s products. Coffee grinders, toasters, pocket calculators, radios and hi-fi equipment came next, all designed on the same principle: “Weniger, aber besser” (translation: “Less, but better”). Over half a century, Rams designed almost 500 products. They are exceptional in their beauty, functionality and design. And did I say there were 500 of them? That number stops me cold. It’s like a golfer shooting hole in one after hole in one.

Private Splendor: Great Families at Home

Butlers have not gone extinct at the eight palaces Alexis Gregory explores in this remarkable book of historical essays and double-page photographs. But they aren’t usually on the permanent staff, as they were in the not-so-long-ago days when Prince Johannes von Thurn und Taxis had 200 on the payroll, ten of them footmen. (The Prince was a special case — his family founded and owned the German post office, and when the government confiscated it, the Thurn und Taxis were given the castle as a consolation prize.) Many of these houses are now open to the public. Some have been carved into apartments; with luck and connections and a sturdy checkbook, you could live in one. But not in the rooms photographed here. These rooms are for the occasional tour. These rooms are for private parties. But these rooms are not, in the main, for photographic display.

Santiago Calatrava: Complete Works

Four years after 9/11, no one could decide on the buildings that would replace the World Trade Center or the memorial that will be erected to honor the dead. Then Calatrava was hired. He went wildly over budget. But he made something fantastic. White as bone, arched like a fish and ornamented with white steel that looks like fish bones radiating from a spine, it’s like nothing Americans have ever seen. There’s a reason: The architect of the first building to be erected on this iconic American site isn’t an American.

The World of Madeleine Castaing

The color combinations are like nothing you’ve ever seen. Often the rooms are almost empty. Instead of a framed painting, you might find that Jean Cocteau has drawn on a wall. Why isn’t Madeleine Castaing a household name?

Because she’s impossible to describe in a sound bite. She was French — born near Chartres in 1894, dead at age 98 in 1992 — but you can’t really say she was a French decorator. “I can take inspiration from a scene in Chekhov as from a dress by Goya,” she said, and she wasn’t kidding. In one of her rooms, you could be in Russia, in another room London. Most of the time, the mood she created was timeless, poetic, a fantasy. As she said, “There is always beauty in mystery.”

Buckminster Fuller

For a genius, he’s not very well known. In the 1930s, he invented the Dymaxion Car, a three-wheeled, teardrop-shaped vehicle that carried 11 passengers, got 30 miles per gallon and topped out at 120 miles an hour. And then there was the Dymaxion House — round as a top, aluminum, extremely weather resistant. And never mass-manufactured. In the 1940s,his realization that the triangle is the strongest shape in nature led him to invent the geodesic dome — and the geodesic home. Huff and puff all you want, domes are all but impossible to blow down. And shockingly cheap to build. But his greatest invention was in the realm of ideas, Long before Stewart Brand slapped a picture of the Earth on the cover of the Whole Earth Catalog, Bucky Fuller was thinking about the earth as a spaceship. He started with a simple truth: There is one outstanding important fact regarding spaceship earth, and that is that no instruction book came with it.

I Shock Myself: The Autobiography of Beatrice Wood

“From early childhood, I wanted to know what the world was like, willing to pay any price to understand humanity,” Beatrice Wood wrote. “I paid the price.” Yes. She did. But she got what she was looking for. She won the Grand Prize.

Beatrice Wood (1893-1998) would be a National Treasure in Japan for her ceramics; in our country, she’s a footnote in the history of art. But her work isn’t why those who knew her cherished her and those who have read her book see her as a kind of life coach. Consider: She was born rich, resisted her controlling mother, lived on the edge, knew everyone, had terrific love affairs, re-invented herself several times and died, happy, at 105.

And, of course…

Monsieur Proust

In 1913, Marcel Proust’s driver, Odilon Albaret, married a young woman from a small mountain village. Celeste knew no one in Paris, and her loneliness mounted. Proust suggested that she deliver copies of his new book to friends. And so it began. Messenger, housekeeper, confidante, friend, nurse — until his death in 1922, Celeste Albaret spent more time with Proust than anyone else. Indeed, she spent so much more time at Proust’s home than she did in her own. As her memoir attests, she begrudged not a minute of those hours in his service. Early on, she left Proust’s apartment to go to church. “There will be plenty of time for that after I’m dead,” he said. She never went to church again while he was alive. Proust — the man and the writer — came first. “Time contained no hours,” she writes, “just a certain number of definite things to be done every day.” And yet, no matter how exacting his demands, she never entered his room without a smile.